Google, stupidity, and libraries

By Kim Leeder

As a teenager, I never tried drugs because I didn’t like the idea of any substance affecting the processes of my brain. It never occurred to me that the long hours I spend working, reading, and researching in front of a computer could have a similar effect.

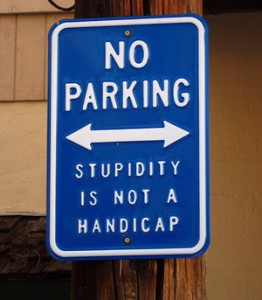

Photo by Flickr user Bill Gracey (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Recently I found out that it could be happening to all of us: Google and the Internet as a medium could indeed be changing the ways our brains function and process information. “As Marshall McLuhan pointed out in the 1960s,” writes Nicholas Carr in The Atlantic, “media are not just passive channels of information. They supply the stuff of thought, but they also shape the process of thought. And what the Net seems to be doing is chipping away at my capacity for concentration and contemplation.” Carr’s article in the July/August issue of The Atlantic, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?,” received some attention for accusing its readers of not being able to accomplish deep, sustained reading in the age of the Internet. According to the article, the Web is reprogramming our brains in a fundamental, biological way. (Note: for a smart, satirical look at the issue, check out Stephen Colbert’s interview with Carr).

The responses to Carr’s article came from both sides of the fence: those who agreed with with him and those who objected to the perceived insult to their intelligence. The Chronicle of Higher Education came out with three articles that expressed concern and agreement: “Your Brain on Google,” a compilation of somewhat ironic quotes from the Web, “On Stupidity,” an extended book review of “a cartload” of recent books on anti-intellectualism, and “On Stupidity, Part 2,” an English professor’s response to the problem. Meanwhile, The New York Times Technology section printed a counterpoint by Damon Darlin, “Technology Doesn’t Dumb Us Down. It Frees Our Minds,” that accused Carr of being a technophobe and insisted that “writing, printing, computing and Googling have only made it easier to think and communicate.”

The irony of the entire argument is encapsulated in the first two lines of the New York Times article: “Everyone has been talking about an article in The Atlantic magazine called ‘Is Google Making Us Stupid?’ Some subset of that group has actually read the 4,175-word article.” Darlin builds the satire by attempting to sum up Carr’s article in a Twitter “tweet” of less than 140 characters, but only skims the surface of the real irony: the likely truth that very few of the people discussing Carr’s article had been able to read the whole thing. There’s something amazing and a bit disturbing about a culture in which everyone’s opinion is equally important and valid, no matter whether or not one has even a basic knowledge of the subject.

As an academic librarian, I’m particularly interested in the implications for libraries of Carr’s article. Hand in hand with Carr’s concern about a growing inability to engage in deep reading is the equal possibility of a growing inability to engage in sustained research. Google leads us to believe that searching for information is easy when library research is complex, often frustrating, and full of twists and turns. So the next question is: does it have to be that way? It’s a given that library systems tend to be overly complicated, even for simple searches. The common refrain is: how can we be more like Google?

The followup question is: do we want to?

These days academic libraries are grasping at every possible product—from federated searching to LibraryThing—that might ease our students’ apparent impatience with the challenges of research. After all, the 2002 Pew Internet & American Life report, “The Internet Goes to College,” made it clear that our students rely on the Web first when they’re doing research, and generally use the library only as a latter resort. If academic libraries don’t make it easier for students to find relevant information for their course projects, they may not come at all. We may as well just hand Google Scholar the keys.

On the other hand, a recent study of the research practices of college students in the humanities and social sciences offered more heartening results. Alison J. Head’s article, “Beyond Google” in First Monday (later written up for September 2008’s College & Research Libraries) found that students are using libraries in greater numbers—and earlier in their searches—than the Pew Research Center would have us believe. Granted this was a study at a single, small, liberal arts college that doesn’t necessarily reflect the situation everywhere. But we can glean some optimism from the study, along with the requisite grain of salt.

On the positive side, academic libraries have the benefit of a captive audience of students whose professors often require the use of library resources. While we may hope that these requirements train students in the ways of deep research, the day-to-day interactions at any academic reference desk would indicate otherwise. Instead, a majority of students reflect a desire to find adequate sources for a given project as soon as possible, even if those sources are not ideal. Is it Google that has raised their expectations for how quickly an information search can be accomplished? A study from the British Library calls this a “truism in the age in which we live” that “crosses all generational boundaries in the digital environment…. The speed of new media has cultivated a lowered tolerance for delay.” The study goes on to say:

There is considerable evidence to support the view that many students do not explore information in any deep or reflective manner. The lack of any evaluative efforts on the part of information users has been documented…. According to Levin and Arafeh (2002) most students stop searching at ‘good enough’ rather than trying to find the best source etc. Some ‘view the Internet as a way to complete their schoolwork as quickly and painlessly as possible, with minimal effort and minimal engagement.’

English professor Thomas H. Benton’s personal observations are nearly identical. In “On Stupidity, Part 2,” he writes:

Essentially I see students having difficulty following or making extended analytical arguments. In particular, they tend to use easily obtained, superficial, and unreliable online sources as a way of satisfying minimal requirements for citations rather than seeking more authoritative sources in the library and online. Without much evidence at their disposal, they tend to fall back on their feelings, which are personal and, they think, beyond questioning.

The echo of Carr’s article in both of these quotes is unmistakable. Whether or not Google is actually changing the biology of our brains it is difficult to say, but it does seem possible that Google could be damaging our students’ ability or inclination to conduct real research.

I’m not blaming our students. It is not the fault of anyone in particular if they are losing the interest and ability to conduct complex research. They are products of their culture, just as we all are. Just as I am.

In fact, those of us currently in our early to mid-thirties are in a unique position to address this issue. You see, I didn’t grow up with computers, but computers and I grew up together. I can remember, back in grade school, Atari and I bumbling our way through Asteroids. In high school, America Online and I had our first heady experiences in online chat rooms. When I went to college my library’s young OPAC was incomplete and I still had to use the card catalog to find certain items. Computers were leaking into my research in college, but their effect was fragmented. Google was founded the year I graduated from college.

I grew up with computers, but I grew up knowing that they were fickle, fallible, and constantly changing. I still have a collection of old floppy disks with files I will never be able to access again. I greatly enjoy technology, but I maintain a certain skepticism about it.

That said, I had to make a conscious effort to read Nicholas Carr’s article all the way through. The first time I linked to it, I skimmed the first few paragraphs and bookmarked it. The second time, I skimmed further into the text. I didn’t actually read the whole thing until I chuckled at Darlin’s observation on how few had read it and realized that I was not one of them.

What happens to our libraries in a culture where sustained reading and deep research are skills that our students and patrons increasingly do not value? There is no easy answer, but the most critical thing we can do is reflect passion for our work and share it with our students. Benton writes, “Effective teaching requires embodying the joy of learning — particularly through lectures and spirited discussions — that made us become professors in the first place. It’s extremely hard, but teachers have been doing it for generations.”

Notice his admission that playing such a role is “extremely hard”; we can all appreciate his honesty there. It is hard to be an intellectual in a culture that values actors over educators. It is hard to face a constant onslaught of superficial research when we know how much richer and more inspiring information can be. But the payoff comes when we open the door and a student steps through, leaving Google aside for the moment, to consider the wealth of research tools at their disposal that they never knew existed.

If only it happened more often.

It’s your turn: Do you think Google is affecting us? Click here to take a short reader survey.

Many thanks to my ITLWTLP colleagues Derik and Brett, and to Rick Stoddart, Tom Hillard, Ellie Dworak, and Elaine Watson for offering feedback that helped shape this post.

I haven’t read the article (yet, it’s on my “to_read” list in delicious), but I’ll jump in anyway.

If the mode of information shapes our thought, I wonder if the online, hyperlinked mode of information is adding a benefit of interconnectedness to our thoughts. Are we better seeing the linkages between ideas even if we are spending less time in extended concentration.

I also question if the physical medium is as much the problem as the mode. The technology is still not quite there where people want to read long text on a screen. As screen tech improves perhaps our desire and ability to read longer and more in-depth will be correspondingly improved.

There’s a lot of focus on making information easier to find. I really don’t see that as directly corresponding to less thinking. In a world where information is easier to find, the focus of instruction (by professors not just librarians) needs to focus on the critical thinking on, evaluation of, and linkages with various streams of information. Those are skills needed by everyone, and those are skills that need to taught (starting at an early age). Those are skills where people are failing.

p.s. Still don’t think that’s “irony” up in paragraph 4.

I’ve read it. I was nonplussed. (Warning: cranky psychology major ranting about to begin…now.)

I’d find most of the research cited (poorly) by Carr and the British Library to be more compelling if we had older data to which we could compare it– but we don’t. We can postulate all we like, but there’s very little evidence as to what kind of change Google is making on is, if any at all. Is it really changing the way we see information, or is it just catering to tendencies that we already have– hence its popularity?

What’s entirely possible– and something none of us like to admit– is that in our culture “sustained reading and deep research” have never really been appreciated. While, like Carr, I lack data, I do know that as a child in the 80s, I was “weird” for wanting to read nonfiction books for fun, and my mother, a very intelligent and skilled critical care nurse, admitted to me that she was intimidated by card catalogs and libraries.

Perhaps only now that we’re able to more easily track search habits and gauge attitudes towards research by ordinary people, it may seem that “deep research” is no longer valued. But is that really the case, or does it just seem that way since more people are capable of doing deep research than ever before, though they still don’t really like it?

I’ve never read every word of any book or article I’ve ever read.

As a young person I learned that skimming an article was far more efficient than reading it word for word. And this was long before Google or the Internet.

Google is simply a part of the “need it now” culture. Just look at the nightly news: everything predigested into easy-to-swallow soundbites.

For another take on pop culture and intelligence check out “Everything Bad is Good for You” by Steven Johnson

Jenny: That’s a great point(s).

As Derik points out, I think (as one who hasn’t read the article, but based on your post) that much of this has to do with education and educational systems and philosophy that students are subject to at a very young age. Critical thinking is a skill that needs to be trained and developed. I wonder to what extent parenting, as well as elementary and secondary education has to do with the ability for students to think critically, i.e. go beyond the “I need it now” from Google.

In general, what I am trying to say is that I think Google syndrome needs further investigation to answer questions of:

What is different between critical thinking skills and utility of students before and after Google?

What socio-economic/geographic backgrounds might play into how students learn and utilize critical thinking?

Is it lack of critical thinking or sheer laziness?

I am also apt to lay blame to our current educational system. Students attend college in huge classrooms and frequently anonymous environments. This remains a challenge to instructors and professors at universities who are dedicated to educating students and assisting them in developing critical thinking skills.

Those schools that generally focus curriculum on developing critical thinking and inquiry in students are those schools that are more expensive and provide a smaller classroom experience. Not that we can ever resolve such disparities within our current system…

oh, and just as I wrote this previous comment I noticed the following link on my RSS feed from my delicious friends: Cognitive Evolution. Could be an interesting read about evolution of cognition and how technology influences it!

Hi Kim: I can’t access Evan R. Goldstein’s compilation of ironic quotes from the web at The Chronicle of Higher Education on Carr’s essay. Was it really interesting? I would like to read it but I really can’t afford a subscription or web pass.

Hi Jan, the quotes were collected from sites around the Web, which makes them more interesting to me because it wasn’t an interview. So these are unself-conscious comments that still offer a flavor comparable to the Colbert interview with Carr.

I could send it to you if you give me your email address…

Perhaps we are not challenging students with “deep research” questions. If a freshmen can effectively meet the standards of a college paper by finding three sources from one Google search, then maybe professors need to change the curriculum to make it harder for students to find relevant sources. I think the problem is not that students have a vast wealth of knowledge at their finger tips, it’s that they are only asked to write papers about “Wolves in Idaho” or the “oil crisis”. Sure, if they wanted to they could spend hours at the library studying these topics, but Google gives me 1,330,000 hits for “Wolves in Idaho” and 6,090,000 hits for “oil crisis”.

I think we have a 20th century education system with 21st century students.

@Derek: Thank you.

This is a sore spot with me– I’m not sure if it’s the cognitive psych undergraduate background, or the deep love of research that I’ve always had (“You want to stop there? But…there’s this book on ancient Egyptian burial customs among the lower classes! Doesn’t that sound like fun…oh, okay.”)

@Emily: Such great questions…I don’t know if we have the data to answer them. I don’t know if we’ll ever have that data, actually.

But your question “Is it lack of critical thinking or sheer laziness?” makes me wonder– how would you tell the difference between the two? At some point, critical thinking begins to come naturally to young people; one of the byproducts of puberty is a development of abstract thought. Is it the fault of student for not applying to their work the same vigor of inquiry they apply to American Idol or parsing of Facebook wall posts? Or is it the fault of educators for not demanding such rigorous work? Both, maybe? I don’t know– I know these questions are too knotty to answer here.

@Jim: I like the point you make. Or, as a rejoinder: you could help faculty members devise curricula and assignments that simultaneously press the relevance and difficulty of research as well as the subject matter of the class. Of course, you’d need the faculty member’s tacit approval, and agreement, and willingness to share stage time…all of these things can be hard.

I’m firmly in the Jenny Parsons and Jim Duran camp. I’m not convinced that people are any dumber than before, and I’m not convinced that students won’t rise to the occasion if taught properly and given appropriate, challenging assignments.

You might also be interested in what Wayne Bivens-Tatum has written on another, similar publication, The Dumbest Generation?

Kim – great post – thanks for challenging me to think about more than just ARL statistics this week!

It’s definitely more than just Google, search engines, and other quick-snippet rides into the info landscape that lead to suggestions that Google is making people tend toward do just enough to get by. We’re all distracted and easily distract-able because of the pretty huge amount of info made available. We’re all being asked to do so much more, respond to anything and everything, have an opinion on a broad swath of topics rather than develop deep thoughts about a few things. I also think that for students in particular, skimming the surface of most things is normal. And what they do conduct deep research on is determined by what they value at a particular time in their lives – and I don’t honestly think that the period of time from teens to twenties is when they actually value deep thinking about school work (with exceptions, of course). I do agree with your suggestion that certainly a role of libraries is to be a place where deep thinking can happen – when the conditions are right – and what librarians can do is to foster those conditions and invite students to ask themselves deeper questions while helping them find x number of references for the paper that’s due tomorrow. I’m also not saying that students are incapable of deep research, I just think that an issue has to mean something to them on a personal level for it to be possible to dive deeper.

Just my two cents.

@Steve: I’ve got it on my to-read list. From what I can tell, it’s one of those things I need to read when I’m in one of my more patient moods. Starting on it after reading Carr’s article may make me go ballistic– not fair to the author. (Or to Carr, truth be told. :) )

@Hilary: I think you’re right where libraries are concerned. Regardless of whether or not Google and its ilk really are changing the nature of research and scholarship, a library can’t motivate a student who isn’t interested in learning to begin with.

But of course, if something magical happens, and the student’s mind is changed…then, yes, we should be there. And the student should know to come to us, because we were helpful to him or her when they just needed so many articles or references for their papers.

Hi Kim: That would be great. The Colbert Report interview wasn’t that great. Too short and jokey, albeit entertaining. My email address is fortuneontherocks at yahoo.com. Thanks.

I’ve read Carr’s article (all the way through. In fact, I sat in a public library and read it in the actual, physical Atlantic magazine, while on vacation in South Dakota). It was some time ago, but I remember finding the article quite thought-provoking.

An under-appreciated book on this issue of technology and its effect on us and our culture is “Technopoly” by Neil Postman. Though written in 1993, it’s still quite relevant. One of the author’s major points is that every technology has positive and negative effects: e.g., books let us record our history, but perhaps we have lost some of our personal ability to remember. Postman would have us think about and reflect on the good and bad of any new technology.

Lots of people get upset when someone (like Carr) discusses the potential negatives of a new technology (like Google), but no one seems to notice that most everybody else (including us in library-land) are just singing the praises of every new technology without considering their ramifications.

Pingback : New library blog « Level 1 Librarian

I’m coming here one year after the post. Thank goodness for internet!! Thanks for the excellent post and fantastic comments you all have made.

Especially Jenny’s point that we don’t have data to compare to is spot on! I never liked these “we have lost the golden days” -rhetorics. When i ask when exactly was there such a time that everyone loved to read things properly and think things over thoroughly, i never seem to get an anstwer. Such a time is perpetually in the past. Aristotle wrote about it, didn’t he.

One more thing: i happen to know librarians’ often check the google before delwing into their own Quality Databases Of Meaningful Knowledge, even if they would silently disapprove other people doing so.