A Look at Librarianship through the Lens of an Academic Library Serials Review

Photo by Flickr user Elvie.R. (CC BY 2.0)

By Annette Day and Hilary Davis

Talk to any librarian or library vendor and you’ll hear the same thing – the global economic downturn is hitting hard. Libraries everywhere are taking an axe to their collections; libraries are cutting book budgets, canceling serials subscriptions, allowing institutional memberships to lapse, and letting go of databases. Libraries and their stakeholders are having to make some really hard, realistic decisions about how much they can do without, while still maintaining adequate support for learning, research, and teaching. The experience of a serials and databases review– reviewing all continuing expense obligations– can be a painful, traumatic process for any library. But it can also give a library some tremendous insights into its collection, its level of credibility within its parent organization, and just how well-positioned it is to fully support the needs of its constituents. A review can unveil some interesting issues in the business of librarianship, publishing, and scholarly communication – from the tools and skills necessary to make value judgments about a library collection to the potentially fatal future of some segments of the publishing industry. In this article, we outline the steps of a serials and databases review from the perspective of an academic library and unpack some of the big issues and questions that face our profession as surfaced through the experience of a conducting a review.

1. Identify the Serials and Databases

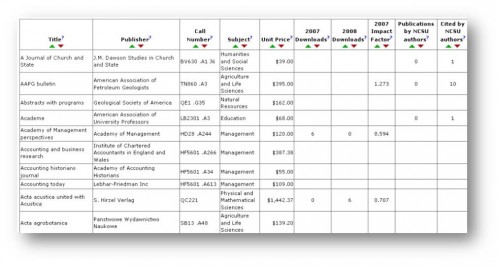

To successfully undertake a serials review you of course need a list of everything to which your library subscribes, how much you pay for each serial and database, and the dollar amount you have to cut to meet the bottom line. Wherever possible you also want to gather data elements that, combined with cost, campus feedback and librarian knowledge, will help you ascertain the value each title brings to your community. Some of the more common data elements librarians utilize in a review exercise are: vendor supplied usage statistics, impact factors, information about journals your constituents are publishing in and citing, and alternative access via databases that aggregate full-text journal content. This list of potentially useful collection metrics is certainly not definitive but it represents those data elements that are heavily relied upon by most libraries (for more see the metrics described by Guy Gugliotta).

The above sounds a simple proposition, but the ways in which libraries subscribe to journals are not simple. For instance, journals and databases may be subscribed in a multitude of ways: through a package of journals/databases from a publisher, on the basis of an institutional membership, or through a consortial deal whereby access to a given resource is shared by all libraries in a consortium due to the fact that one of the member libraries subscribes to the journal. Unfortunately, the tools available to us to manage and account for complex subscriptions don’t yet meet all of our needs. An ILS (Integrated Library System) will likely work with the concept of an “order,” but an order doesn’t necessarily correlate to journal titles or other ways that journals can be purchased such as packages and memberships. If an order is for a journal package, say the ACM Digital Library, only one record with the associated package cost may appear in your ILS. The order is, in reality, for each of the 30 journals contained in that package but the native ILS has difficulty with that concept. Generating a comprehensive list of subscribed journal titles and their associated costs from an ILS is far from straightforward, and in our experience no ILS is currently set up out of the box to work that way. If you were to ask your Acquisitions librarian, they would tell you that the issue goes even deeper – the way that serials agents and publishers set up the billing structure for libraries can dictate how libraries are able to describe the order and its related parts.

Consequently, a lot of larger libraries have turned to an ERM (Electronic Resource Management system) as a way to try to tackle some of the inadequacies of today’s ILSs. Theoretically, an ERM helps libraries maintain a running inventory of journals to which they provide access (either paid or free), if they paid for them during the current fiscal cycle, the cost paid (either as an institutional membership, or as a subscription to a single title or a package of titles) and the library’s rights to the content for which they have paid (i.e., can the library claim perpetual ownership of the content or is the library simply leasing current access?). Many factors have to be triangulated to reasonably determine if you’re getting good value for your subscription money. Having this information collected in one place in preparation for a serials and databases review is critical, especially if your subscriptions have soared beyond 100 or so. However, based on our own experience and talking with other libraries, no ERM is truly positioned to combine all of these pieces in a way that is efficient and accurate. A great deal of time and attention is needed to handle extraction of data, normalizing the data (e.g., the concept of “usage” and “downloads vs. accesses” is not applied consistently internally or externally by publishers/vendors), cleaning up the data (e.g., compiling cost data from multiple order records for thousands of subscriptions and variations in how serials are packaged), and interpretation of the data.

The bottom line is that current ILS and ERM solutions are imperfect tools for comprehensively supporting a major serials and databases review to achieve cancellations and save money. What is needed from these kinds of tools is a way to co-locate order information with use information and provide a system to collect feedback from a user community to help determine the relative value of journals and databases when we have to make cuts to the collection.

2. Communicate with Users

A major component of a serials and databases review is communicating with your users why a review is necessary, laying out how it will work, and making clear what kind of feedback is needed from them. It might not be the easiest dialogue to have with your community, but it is a prime opportunity to have honest, open conversations that will educate your patrons and address many of their commonly held misconceptions and anxieties.

In order to make the best decisions on what resources to keep and what to cancel libraries have to actively solicit feedback from their communities. This is usually done in a combination of ways – meetings between librarians and faculty, emails to campus, and a web presence designed to communicate the reasons for the cuts and the mechanisms for providing feedback. Some examples of websites created for this purpose are from North Carolina State University Libraries, and the University of Maryland Libraries.

Some libraries will ask for feedback on a list of every single journal and database to which they subscribe while others attempt to share only the content that isn’t deemed a “no-brainer” to keep. While the idea of providing as much information and data as possible to your users can be compelling, it has its drawbacks. Is a data-driven approach the best method for getting feedback from constituents? You want to balance giving your users enough information to make informed decisions, but you don’t want to overwhelm them with information that they either don’t care about or that takes lots of explanation. Journal cost, subject, usage statistics, impact factors, and the journals in which your constituents are publishing and citing (supplied by the Local Journal Utilization Reports (LJUR) from Thomson ISI) are all standard metrics that will likely resonate with library patrons and that can easily be conveyed with each title on the list for review.

What does it mean to “keep or cancel” a journal? A common misconception from patrons is that the print and online components or formats of a journal are “always” distinct and that canceling one format means that the other will still be available. Of course, we know that this is not always the case as, often the cost of the print is tied to the online version (and vice versa). This is an opportunity to dispel another common misconception about potential cost saving by going electronic-only (dropping the print and maintaining only the electronic format of a journal). Realistically libraries rarely see more than 5% savings by dropping print subscriptions but many patrons (usually faculty) expect the savings to be higher and are often startled that the cost of the journal isn’t halved by removing one format. From the publishers’ perspective the production costs of publishing journals, regardless of format, play heavily into the prices that libraries pay, hence the minimal savings.

What about preservation for the long-term? One common anxiety that librarians still frequently meet is centered on the loss of the print journal. Most libraries have moved large chunks of their journal collections to electronic only formats. The desktop convenience provided by the electronic format is expected by our patrons and the downstream cost savings that libraries can realize is beneficial. Patrons have embraced the electronic format, yet when asked about canceling print counterparts (if you still have them) many users are reticent. Sometimes their concern is tied up in the traditional notion of the library as a large print archive where researchers can serendipitously discover content by browsing in the stacks. In other cases, patrons are shocked that in the digital world libraries haven’t done a straight swap from shelf space to server space. The fact that, in most cases, these electronic materials do not reside on a local server, but are maintained on publishers’ servers across the world makes it hard to convey the shifted concept of ownership in the electronic world. Libraries can negotiate for rights to own the electronic content just like it can own the physical item sitting on the shelf, but if that content resides on someone else’s servers, some patrons, perhaps rightfully, are distrusting of a move away from the print world and fearful for how we can successfully safeguard these materials for future generations. With the economic crisis providing the final nail in most print journal coffins, this is a great opportunity to educate your patrons about the concepts of archival and perpetual rights, explaining what options are available, such as LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe) and Portico.

What about other parts of a library system budget? A serials review brings to light the diverse services a library provides and the breadth of the patron-base the library supports. When asked to help make hard choices about cutting collections, some patrons may look to other library-provided services and question why the library thinks those services are more important than their favorite book or journal. Reading room renovations, computer equipment refreshes, and laptop lending are services that might seem peripheral to one user but may be central to another user’s learning and research experience. Any serials review will likely raise the thorny issue of how a library prioritizes resources, and reconciling that balance for some patrons will be difficult. The intricacies of university and academic library budgeting may not be what they want to hear about, but it is important to clearly explain, for instance, how a reading room renovation is supported with a budget source that is distinct and independent from the budget source that supports journals and databases.

3. Evaluate Feedback

Photo by Flickr user Nicole Hennig (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Once you’ve collected the community feedback, the process of combining all of the information available about each of the serials and databases begins. We’ve referred to journal package and consortial dependencies already, but at this stage these issues truly make or break the decision to cancel a journal or database. Does it make sense to dismantle a package of ten journals simply to be able to cancel two titles if the cost of canceling those two titles doesn’t save more money than keeping the package of ten intact? Consortial dependencies are even more complex. Your library may have access to a title based on the fact that another library in your consortium pays for a set of journals or databases, so the decisions made by that library to keep or cancel resources could severely impact the ability of their consortial partners to maintain a collection that best serves users. Often, large journal packages are negotiated by a consortium of libraries and the savings that result from going in as a group can be compromised if one library decides to back out of the deal. The downstream effects of canceling journals and databases can build rapidly when these dependencies are in place.

Beyond package and consortium dependencies, the process of weighing the variety of metrics associated with journals and databases can be rather tricky. Not all journals and databases provide usage statistics or impact factors. There has been much written (e.g., Pikas, 2007; Davis and Price, 2005) about the reliability of usage statistics, even in light of existing standards for measuring electronic journal use. So, how do you balance the lack of metrics for some resources with the need to determine value of the resource to your community? To what extent do you trust usage statistics when they do exist (this might be a whole article in it’s own right)?

These are just a few of the tricky issues that must be weighed when evaluating feedback and combining it with the data you may have. The bottom line is that a serials and databases review cannot and should not be entirely data-driven. The presence of data for some resources and the absence of data for other resources needs to be carefully weighed with the advantages and disadvantages of dependencies as well as the librarians’ expertise and knowledge about the research, teaching and learning needs of community. This is the value that collection management and acquisitions librarians bring to the table during critical budget cuts.

4. Decision-Making – What to cancel and what to keep?

Analyzing the feedback will hopefully have given you a clear idea of any “dead wood” that may be floating in your collection. If you are extremely lucky then you may be able to stop there, but the realities of today’s economic climate forces libraries to cut to layers far below the “dead wood.” Tackling these deep cuts is truly painful, and at the final stage of the serials review requires the impossible task of balancing the campus feedback with your budget reduction target. You need to make the best decisions to minimize the impact of the collections cuts on teaching and research, preserve a balance between different subject disciplines and user groups, and refrain from strangling collections flexibility and growth for years to come. Really simple, right?!!

For most libraries, the strategies used to deal with collections cuts focus on some combination of cutting serials, reducing the monograph budget, going online-only (if you haven’t already), cutting standing orders, reducing the binding budget, and canceling databases. It is extremely tempting to shift the heavy lifting of the cuts to the monograph budget and shield the continuing resources from the cuts. A year or two of buying considerably fewer monographs sounds manageable and will likely have less immediate impact. However, unless your budget cut is a one-time reversion and everything will get back to normal next year, then be very cautious in hitting your monograph budget disproportionately from other collection areas. Most academic libraries probably have between 75% to 98% of their collections budgets tied up in continuing resources. The bigger this proportion the more vulnerable your budget is to inflation. Serials inflation is on average about 8% a year, while monograph inflation is much lower. The cushion provided by cutting the monograph budget will be eaten away quickly, and you will again be faced with cutting continuing resources just to keep inflation at bay. The act of building a collection quickly reaches the stage where it is one in, one out – nothing new can be added unless something is canceled. The collection cannot grow or be nimble enough to respond to new campus initiatives, it can only remain static. Keeping a balance between serials and monographs is critical so that collections breadth, flexibility and growth are not lost to combating inflationary increases.

A Few Lasting Implications

It will be hard to recover from substantial cuts for consecutive years, and the impact will be felt for years to come as gaps in collections begin to appear. As collections budgets continue to diminish leaving ever-widening gaps in collections that cannot be filled retrospectively without a large influx of money, libraries may well begin to step away from the notion of broad and comprehensive research collections. Access to materials at the point of need will become the main focus with patron-driven collecting or access models becoming primary strategies. Take a look at the Taiga4 statement:

“Within the next 5 years collection development as we now know it will cease to exist as selection of library materials will be entirely patron-driven. Ownership of materials will be limited to what is actively used. The only collection development activities involving librarians will be competition over special collections and archives.”

This statement may at first seem outlandish, but has strong foundations in what we see happening now. With collections cuts, Interlibrary Loan (ILL) is becoming a key service for every library, ILL is the ultimate on-demand service. We also see libraries investigating and investing in user-driven collection models for their monograph acquisitions. These models are seen mainly in the e-book landscape with platforms such as EBL and MyiLibrary working with libraries to offer ownership combined with on-demand collection building models. Other libraries are working to include print books into their on-demand collecting (Spitzform and Sennyey, 2007).

All of these developments will produce some major changes in the publishing industry and perhaps ultimately in scholarly communication. Libraries have been the main market for high level research monographs and journals over the years, but that market has been shrinking and will no doubt continue to diminish in the future. The large publishers will find some way to adapt, but the small publishers may not. Small publishers don’t have the revenues to “retool” their products and pricing options to change with the times. Some are still unable to provide standardized usage statistics (if any), and still others haven’t made the move to produce their journals electronically.

Other impacts of a serials review are captured in all of the backend work of a library’s technical services team (acquisitions, metadata, and cataloging) and the work they conduct with the serials agents and publishers. Journal cancellations and conversions to electronic -only format will certainly imply work down the road to edit and update catalog records. Subscription cancellations may also result in reduced discounts with subscription agents as your spending decreases. As a consequence, renegotiation of service agreements with serials agents and even new license agreements with publishers will be likely. The work required to act on the decisions made as a result of a serials review can instigate a great deal of costs in terms of time and staff to actually make the changes a reality.

The impact of substantial collections cuts across a large number of academic institutions will be felt immediately by the scholarly publishing industry. Longer-term implications for how research collections are built and the nature of scholarly communication are unclear. Many possible outcomes exist and libraries need to take a lead role in shaping their futures so that they still remain central to the learning, teaching and research needs of their constituencies.

Many thanks to our reviewers who helped shape this article: Derik Badman (ItLwtLP), Kristen Blake (NCSU), Maria Collins (NCSU), Emily Ford (ItLwtLP), and Greg Raschke (NCSU).

References/Further Reading:

- Davis, Philip M. and Jason S. Price. 2005. “eJournal interface can influence usage statistics: Implications for libraries, publishers, and Project COUNTER.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, v. 57, no. 9: 1243-1248.

- Gugliotta, Guy. 2009. “The Genius Index: One Scientist’s Crusade to Rewrite Reputation Rules.” Wired Magazine: http://www.wired.com/culture/geekipedia/magazine/17-06/mf_impactfactor?currentPage=all

- LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe): http://www.lockss.org/

- Pikas, Christina. 2007. “It’s about trust, reliability, accuracy…” Christina’s LIS Rant: http://christinaslibraryrant.blogspot.com/2007/03/its-about-trust-reliability-accuracy.html

- Portico (A Digital Preservation and Electronic Archiving Service): http://www.portico.org/

- Project COUNTER (Counting Online Usage of Networking Electronic Resources): http://www.projectcounter.org/

- Spitzform, Peter and Pongracz Sennyey. 2007. “A vision for the future of academic library collections.” The International Journal of the Book, v. 4, no. 4: 185-190.

- Taiga Forum. 2009. “Provocative Statements (after the meeting).” Taiga 4: http://www.taigaforum.org/documents/Taiga 4 Statements After.pdf

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. Copyright remains with the author/s.

Pingback : Libology Blog » Choosing and Choices – Librarianship and Serials

I totally agree. The most difficult aspect is getting instructors to respond in a timely fashion.

Pingback : links for 2009-07-10 « Lawrence Tech Library

@ Joan: Thanks for your comment. We broadcast the message about the serials review a number of ways – through our dedicated library representatives from each academic department, through our University Library Committee, through the campus newspaper, letters from our Library Director to each of the Dept Chairs, etc. Leveraging existing contacts and emphasizing the need to make decisions collaboratively with the campus community is key, and in our experience, seems to work fairly well. What strategies have you used to get your users to provide feedback in a timely fashion?

Pingback : why is serials recordkeeping so problematic? « Across Divided Networks

Pingback : Interesting Post from In the Library with the Leap Pipe « What Now?