The Information Literacy of Survey Mark Hunting: A Dialogue

In Brief: This article makes connections between the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education and the activity of survey mark hunting. After a brief review of the literature related to geographic information systems (GIS), information literacy, and gamification of learning, the authors enter into a dialogue in which they discover and describe the various ways information literacy is both required by and developed through the recreational activity of survey mark hunting. Through their dialogue they found that the activity of survey mark hunting relies on the construction of both information and its authority in ways contextualized within the communities that participate; that survey mark hunting is a conversation that builds on the past, where lived experience counts as evidence; and, that survey mark hunting is both a metaphor and embodied enactment of information literacy. The authors’ goal is for readers to increase their understanding of the Framework and to become inspired to connect the Framework’s concepts to other diverse contexts meaningful to them.

by Jennifer Galas and Donna Witek

“At base there is something more than merely metaphoric about maps and theories; they share a common characteristic which is the very condition for the possibility of knowledge or experience-connectivity.” ((“exhibit 11: Maps and theories concluded,” Maps are Territories: Science is an Atlas: a portfolio of exhibits, by David Turnbull, with a contribution by Helen Watson with the Yolngu community at Yirrkala, 2008, http://territories.indigenousknowledge.org/exhibit-11, accessed 7 Oct. 2016.)) —Maps are Territories: Science is an Atlas, a book by David Turnbull, with a contribution by Helen Watson with the Yolngu community at Yirrkala

Introduction

Understanding, developing, and enacting information literacy is a central concern of information professionals. The ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education ((Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education, Association of College and Research Libraries, 2015, 2016, http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework, accessed 7 Oct. 2016.)) (hereafter Framework) aims to facilitate this engagement with information literacy in the higher education context. And yet, by design the Framework is abstract, anchored by “interconnected core concepts” ((Ibid.)) about information and grounded in learning theories of varying complexity. The question of how to make the Framework’s concepts visible and embodied so that they may be better understood and taught, becoming “the very condition for the possibility of knowledge or experience-connectivity,” ((“exhibit 11: Maps and theories concluded,” Maps are Territories.)) was the genesis of the article you are reading.

We are a systems librarian (Jennifer) and an information literacy librarian (Donna) working in the University of Scranton Weinberg Memorial Library. Jennifer is also a survey mark hunter. ((“About Survey Mark Hunting,” Zhanna’s SurveyStation, Jennifer Galas/SurveyStation, 2016, https://thesurveystation.com/about-survey-mark-hunting/, accessed 7 Oct. 2016. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Survey Mark Hunting,” National Ocean Service, n.d., http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/for_fun/SurveyMarkHunting.pdf, accessed 7, Oct. 2016.

)) Through a conversation in which Jennifer shared with Donna her latest survey mark recovery, we discovered together the extent to which information literacy is required and developed in survey mark hunting. The Framework’s concepts are especially applicable when considering the information literacy of survey mark hunting, and so in the spirit of Schroeder’s Critical Journeys ((Robert Schroeder, Critical Journeys: How 14 Librarians Came to Embrace Critical Practice, Library Juice Press, 2014. )), we entered into a dialogue to develop these connections further.

Related Literature

Jennifer provides a description of survey marks and survey mark hunting in the dialogue that follows. We’ve added citations where appropriate so the reader can seek out further information about the history and practice of establishing survey monuments.

Survey mark hunting relies on geolocational data which is made available through geographic information systems (GIS). Nazari and Webber have made conceptual connections between information literacy and “geo/spatial information,” ((Maryam Nazari and Sheila Webber, “What do the conceptions of geo/spatial information tell us about information literacy?,” Journal of Documentation 67.2 (2011): 334-354, DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00220411111109502. )) and Miller, Keller, and Yore have developed “geographic information literacy” in the K-12 curricular context. ((Jason Miller, C. Peter Keller, and Larry D. Yore, “Suggested Geographic Information Literacy for K-12,” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 14.4 (2005): 243-250, DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10382040508668358. )) Nazari also examines information literacy within GIS as a discipline (geographic information science/systems), and found GIS assignments are typically “geospatial, technology mediated, subject free, and unique in requirements.” ((Maryam Nazari, “The actuality of determining information need in geographic information systems and science (GIS): A context-to-concept approach,” Library & Information Science Research 38.2 (2016): 133-147, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2016.04.005.

)) And Bishop and Johnston consider the importance of geospatial thinking to the work of librarians and information professionals in their decision making and ability to assist patrons with their geospatial needs. ((Bradley Wade Bishop and Melissa P. Johnston, “Geospatial Thinking of Information Professionals,” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 54.1 (2013): 15-21, ERIC, ED EJ1074098.)) The conceptual connections between the geolocating activity of survey mark hunting and information literacy that we offer here complement this body of work.

Our dialogue also addresses the relationship between the puzzling, game-like aspects of survey mark hunting and motivation for learning and practicing information literacy. Nicholson defines “meaningful gamification” as “the use of gameful and playful layers to help a user find personal connections that motivate engagement with a specific context for long-term change.” ((Scott Nicholson, “A RECIPE for Meaningful Gamification,” in Gamification in Education and Business, eds. Torsten Reiners and Lincoln C. Wood, Springer International Publishing, 2015, 1-20, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_1. )) Kim’s summary of gamification as a trend in libraries and higher education ((Bohyun Kim, “Keeping Up With… Gamification,” Keeping Up With…, Association of College and Research Libraries, May 2013, http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/keeping_up_with/gamification, accessed 7 Oct. 2016.)) is a useful complement to Smale’s detailed exploration of the value and uses of games-based learning in information literacy instruction. ((Maura A. Smale, “Learning Through Quests and Contests: Games in Information Literacy Instruction,” Journal of Library Innovation 2.2 (2011): 36-55, available at http://www.libraryinnovation.org/article/view/148/238, accessed 7 Oct. 2016. )) And Deterding provides a roundup of the perspectives of experts on gamification’s relationship to motivation in design. ((Sebastian Deterding, “Gamification: Designing for Motivation,” Interactions 19.4 (2012): 14-17, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2212877.2212883. )) However, nothing to date has been published connecting games-based learning to the Framework, whose lists of dispositions describe motivation, persistence, and curiosity as integral to information literacy learning, ((Framework, 2015, 2016. )) though McGonigal does articulate these dispositions as shared between and valuable to both games and learning. ((Jane McGonigal, Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World, The Penguin Press, 2011.)) Nor have the conceptual and pedagogical connections between GIS-related activities and information literacy been reconsidered in light of the Framework. Our dialogue makes a unique contribution to the literature that bridges these areas of interest and practice, bringing past work in conversation with the Framework.

Methodology and Findings

We conducted the dialogue in a collaborative Google document over the course of two months, following a period of planning in which we developed an outline of broad questions we aimed to address together. The precise questions Donna asked were not known to Jennifer prior to the dialogue. After we composed the dialogue to address our planned outline, we edited it into the version that follows.

Our findings through this process can be summarized as follows: the activity of survey mark hunting relies on the construction of both information and its authority in ways contextualized within the communities that participate; survey mark hunting is a conversation that builds on the past, where lived experience counts as evidence; and, survey mark hunting is both a metaphor and embodied enactment of information literacy. ((Lloyd theorizes the importance of the body and embodied experience to knowing, learning, and information experience, with a focus on the workplace settings and information experiences of emergency services personnel and nurses, arguing that “disassociating the body from research into people’s experience of information literacy effectively limits our understanding of the nature of this experience and has implications for accounts of learning” (Lloyd, 2014, 86). For more see Annemaree Lloyd, “Informed Bodies: Does the Corporeal Experience Matter to Information Literacy Practice?,” in Information Experience: Approaches to Theory and Practice, eds. Christine Bruce et al., Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2014, 85-99, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/S1876-056220140000010003. )) Our goal is to inspire readers to make their own connections between the Framework’s concepts and the contexts that matter to them, and through the process make sense of the Framework and the world with which it is in conversation. In the classroom these kinds of connections are essential to engaging learners in developing information literacy from and through their own lived experiences and contexts, making the dialogue that follows an example of this pedagogical approach in action.

The Dialogue

Survey Marks as Information

Donna: Can you tell us a little about survey mark hunting as a recreational activity—also sometimes referred to as benchmarking or benchmark hunting—how long you’ve been a participant, and its connection to the more popularly known activity of geocaching?

Jennifer: I found my first survey mark in 2002; I began geocaching a bit earlier, in the summer of 2001. Geocaching is the activity in which participants hide a container holding a logbook and small trinkets in an interesting location. They then post the geographic coordinates of the container on a website and other participants use GPS (Global Positioning System) units to locate the container, sign the logbook, and optionally trade trinkets and write up, or “log,” their adventures on websites like Geocaching.com.

Geocaching itself has very little to do with survey mark hunting, but it was through the Geocaching.com website that survey mark hunting as a recreational activity developed and evolved. In 2000, the database for the National Spatial Reference System (NSRS), the primary database of survey marks in the United States, was downloaded with the goal of making the survey marks’ data available on Geocaching.com. Each survey mark was posted to the website as an object that could be searched for and logged, much like geocaches. The intent was simply to provide GPS enthusiasts with another seek-and-find activity they might find interesting.

However, some of us decided to take our interest further and a community developed around survey mark hunting. We learned together, through research and discussions with professional surveyors; we shared our successes, failures, and adventures; and we developed guidelines for those who wish to search for marks and report their findings for inclusion into the NSRS database. This database forms the basis for most recreational survey mark hunting because it is freely available on the Internet for anyone to search.

When we find, or “recover,” a mark, we ensure that we have identified the correct mark by checking that its designation and description are consistent with what we expect to see. We do not take or disturb the mark in any way. We document the mark’s condition and make note of any updates to the description and geographic coordinates that we think are needed. Then, when applicable, we submit our report to the database. If it’s accepted—typically because it adds new, pertinent information and conforms to basic standards—our update will appear in the database within a few weeks.

Donna: Before we discuss the practices and processes involved in survey mark hunting, let’s talk about the survey marks themselves, the coveted objects of the “hunt” in survey mark hunting. When I think of survey marks, they bring to mind infrastructure. Are they themselves a kind of infrastructure, or rather, would you say they’re what enables infrastructure, in a physical sense? What are survey marks?

Jennifer: Surveying is the profession concerned with making accurate measurements of the earth’s surface, on a variety of scales. Surveys are conducted for different purposes, but most surveys result in a series of useful points. Once these points are determined by a survey, they are permanently marked in some way to record and preserve certain information about that point. ((For more on the history of survey marks in the United States see U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, The Preservation of Triangulation Station Marks, U.S. Govt. print. off., 1941, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001483918, accessed 7 Oct. 2016, and, George E. Leigh, “Bottles, Pots, & Pans? – Marking the Surveys of the U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey and NOAA,” National Geodetic Survey: History, n.d., http://www.ngs.noaa.gov/web/about_ngs/history/Survey_Mark_Art.pdf, accessed 7 Oct. 2016. ))

The most common type of survey mark has been in use for over a century. These are brass or bronze disks, typically 9 centimeters in diameter, that are embedded in bedrock, concrete, or other stable materials. Each mark is stamped with identifying information that, taken together with the history of observed data at that point, indicates a point on the earth whose horizontal position (latitude/longitude) or elevation—or both—are known to a specific degree of precision.

The NSRS is a nationwide network containing many of the survey marks in this country. The National Geodetic Survey (NGS) is the agency that maintains the NSRS database; you will also hear it referred to as the “NGS database.”

If we define infrastructure as “the basic physical and organizational structures and facilities . . . needed for the operation of a society or enterprise,” ((“infrastructure,” Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press, 2016, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/infrastructure, accessed 7 Oct. 2016.)) it is clear that the NSRS is both an infrastructure, and an important part of the underlying framework upon which the facilities we typically consider “infrastructure” (highways, utilities, communication networks) depend.

Donna: So, on the one hand survey marks as physical monuments depend for meaning on the information about them that is measured, collected, and stored in the NSRS database; but on the other hand, the use and value of that stored data is quite literally grounded in the physical survey marks themselves, as reference points on the earth. Which leads me to wonder: How do we know where survey marks are?

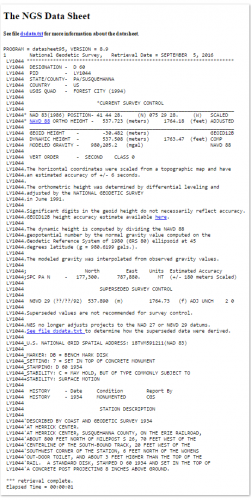

A survey mark’s datasheet provides the information needed to search for the mark.

Jennifer: This question is less straightforward than it may seem in the era of GPS. Datasheets for marks in the NSRS include geographic coordinates, but for marks that have been surveyed only for a precise elevation, the coordinates have been approximated from a map. In such cases, finding a mark requires more information. Sometimes diagrams and, more recently, links to photographs accompany a datasheet.

But by far the most useful and interesting information is in the series of narrative notes that describe each mark’s installation, environment, and nearby reference objects. Unintentionally embedded in these narratives is a history of the area surrounding the mark, as recorded by surveyors that have used the mark over time. The NSRS now also accepts the reports of amateurs—those who have no training in surveying but search (or hunt!) for survey marks and report, to the best of their ability, on the condition of the marks.

To find a survey mark, we rely on past surveyors speaking to us through the datasheet narratives. We hope they identified enough stable points of reference that have indeed stood the test of time, and that they described them in enough detail to find whatever evidence remains. Survey mark hunting provides a lens into the past of the area surrounding the mark. When I locate and identify a survey mark, I’ve found a piece of infrastructure that had a direct role in building the past and therefore the present. I can continue its narrative into the future by contributing to the NSRS database.

Mapping History and its Conversations

Donna: When you describe past surveyors as “speaking to you through the datasheet narratives” I see this as a metaphor for “Scholarship as Conversation,” in which communities engage in the exchange of ideas and information “with new insights and discoveries occurring over time as a result of varied perspectives and interpretations.” ((Framework, 2015, 2016. )) I love the way you connect your process as a survey mark hunter to the past, present, and future of that point on the earth, in which you are in conversation with past contributors to each datasheet. This also reflects the “Information Creation as a Process” frame in how survey mark hunters participate in distinct conceptual and technical processes that result in their reports appearing on the NSRS datasheets. ((Ibid.))

These two information literacy concepts inevitably converge on a third, “Authority is Constructed and Contextual,” which states that “Information resources reflect their creators’ expertise and credibility, and are evaluated based on the information need and the context in which the information will be used.” ((Ibid.)) In the case of the NSRS datasheet, the creation of the information is a collaborative yet situated act, in which many contributors over time construct the narrative log for that survey mark, and yet there is a communally shared understanding of which contributions are likely to be more reliable and hold more authority within the community that uses the database, which includes professional surveyors as well as recreational survey mark hunters.

Can you share a little about the different characteristics and genres of reports surveyors and amateur survey mark hunters submit to the NGS for inclusion in the database? How do you know what information is reliable when looking for a survey mark?

Jennifer: The primary basis for reliability comes from what we know, or can deduce, about the contributors based on their recovery notes. Different groups of people contribute to the database. Each group tends to write with a slightly different voice reflecting their priorities. Property surveyors’ or engineers’ reports might consist almost entirely of numeric data, data that amateurs can’t provide because we lack the equipment or training to take those measurements. Geodetic surveyors may be involved in large-scale scientific projects and are careful to ensure that they’ve described points of lasting significance and stability. Recreational survey mark hunters search primarily for fun and enrichment, and learn and develop best practices iteratively over time.

Each recovery is tagged with a user code, which is keyed to a surveying or engineering firm, a recreational organization, or individual contributors. Optionally contributors may enter their initials.

Excerpt of datasheet with report submitted by Jennifer, showing her user code and contributor initials

The depth of detail and precision of measurements is one indicator of quality, since it is a view into the mindset of the person who made the recovery. I consider it a red flag if the report contains typos, misspellings, or measurements that are obviously wildly inaccurate, or if it otherwise seems carelessly written. The information isn’t necessarily useless, but we would approach it with caution. This kind of judgment takes time and experience to develop, but I know that when I see recoveries submitted under particular user codes, I’m careful to double check their information.

There is one organization whose members earn “brownie points” for survey mark recoveries and as this recognition is the primary motivation for some of their members, in some cases they conduct quick and careless recoveries, or may visit so many in a day that they mix up their notes and log a recovery for the wrong mark. Conversely, there are user code-initial combinations that are consistently accurate, clearly written, and provide useful information for the next person to seek the mark. I also trust recovery notes that conform to NGS standards. Recoveries by large scientific and government entities like NGS are highly regarded because their employees are typically well trained and experienced.

Donna: You describe here characteristics which construct authority in different ways for the information conveyed. The content of each report reflects the author’s purpose for completing the survey mark recovery; this aspect of reading the datasheets is rhetorical, considering author, text, audience, and purpose. Information evaluation, as a process that contributes to information literacy, is concerned with these same things.

You also mentioned indicators of reliability that are shared across many information genres, such as typos and misspellings, and described how a user code-initial combination can build authority over time through the accuracy and reliability of the submitter’s cumulative body of reports. I had to laugh when you described how certain organizations set up incentives for survey mark recoveries and their reports; this reminds me of the incentives for faculty research productivity in the neoliberal academy today, and it can be argued the outcomes of such incentives are potentially similar: sloppy and rushed work of mediocre quality!

Your description of the judgment that develops over time through detailed engagement with the different kinds of information in the reports of past survey mark hunters—whatever their role or profession—sounds like the same kind of judgment I am hoping students will develop through their focused engagement with information, in a multitude of formats, both in and out of their academic programs of study. It sounds like the judgment I aim to develop in my own professional research work. It sounds like information literacy.

Hearing you describe the meaning-making that happens in conversation with the NSRS datasheets and the information they convey, I am wondering if you can speak more about survey mark hunting through the lens (or frame!) of “Scholarship as Conversation.” How are survey marks and their documentation history a conversation that builds on the past?

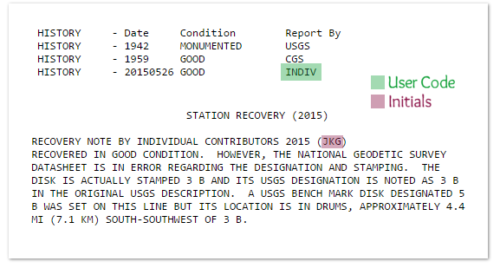

Jennifer: When we add new information to a datasheet, we’re expected to respond to and update (or correct) the information in earlier database entries. Keep in mind that recovery notes are never edited, even if the information contained in them is incorrect, or changes at a later date. So while the most recent recovery note contains the most up-to-date information, to get a sense of the history of the mark you need to read all of the notes from the beginning.

Every time I refer to a datasheet, I get the sense that the contributors are speaking directly to me through time, that I’m interacting with real people and viewing the scene through their eyes, not simply viewing and interpreting data points. Even if the previous contributor has long since passed on, I enjoy finding evidence of the details they mentioned and take pride in continuing the story of that particular point on the earth.

One of my favorite examples is MOUNT DESERT RESET, in Acadia National Park, Maine. On its datasheet (viewable at that link) we see a series of highly narrative, first-person notes from a surveyor who visited the station once a year for three years, beginning in 1931. The original 1856 description was lost, so this surveyor tries to make sense of what he finds at the site. He refines his measurements and hypotheses at each visit to ensure he has found the station that was measured in 1856. He marks the station, originally a hole drilled in bedrock, with a standard disk to communicate the station’s position to those who come later. The notes from the years that follow document changes to the area and threats to the marks, like a new road and parking area. Newer technology is highlighted in the 2010 recovery when a link to digital photos of the site was added to the datasheet.

Other sources of data exist that aren’t as readily available as the NSRS database: for example, datasheets from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), or local surveyors’ datasheets. Sometimes a surveyor or an amateur hunter will discover information about a mark in these other sources, and will add it to their recovery note in the NSRS database. This cross-documentation can help fill in the holes in the conversation by bringing previously “lost” information from the past into the present NSRS datasheet.

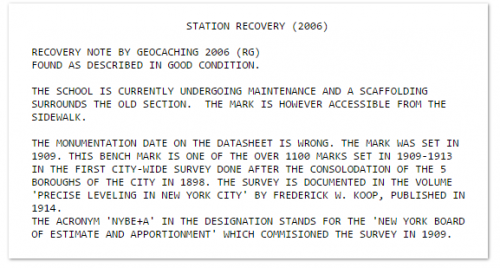

In this example (367 NYBE+A), the contributor does three useful things. He alerts readers to the current (as of 2006) conditions in the area that may affect access to the mark; he corrects the date that the mark was established; and he adds a reference to a primary source documenting the original 1909 survey. It’s exciting to recognize that we’re adding to an ongoing conversation, recording what we see today for use in the future!

The Information Literacy of Survey Mark Hunters

Donna: This analysis for gaps in information, which are identifiable by virtue of the researcher being immersed in the various sources of information for the field of practice in question, is very closely tied to the information literacy frames “Scholarship as Conversation” and “Research as Inquiry.” The first knowledge practice for “Research as Inquiry” is relevant to what you just shared: “Learners that are developing their information literate abilities: formulate questions for research based on information gaps or on reexamination of existing, possibly conflicting, information.” ((Ibid. )) Looking at this knowledge practice as well as the others in “Research as Inquiry,” can you share briefly how these practices play out in your process of survey mark hunting?

Jennifer: The discrete nature of the recovery notes on the datasheets means that often much has changed in the years between recoveries. I usually compare information from different sources (say, topographic maps, current and historical aerial imagery, data from local surveyors and even logs from geocachers) to form a picture of what I might find when I visit the site.

This research can generate more questions than answers. I might discover that a mark I thought was on public land is actually on private land, and then I’ll have to use different research methods to track down the landowner and contact them for permission. I might find a discrepancy between an official recovery note that indicates a mark is gone, while a geocacher has just published a recent photo showing the mark intact.

My search for a particular survey mark in New York City’s Central Park correlates closely with the “Research as Inquiry” knowledge practices. While browsing online digital archives, I happened to find a map of the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, ((Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library, “Map of the city of New York and island of Manhattan as laid out by the commissioners appointed by the Legislature, April 3, 1807,” New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-f4dd-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed 7 Oct. 2016.)) which laid out the original plan for Manhattan’s now-familiar grid of streets and avenues. After developing the plan, New York surveyor John Randel, Jr. and his men spent the better part of a decade establishing survey monuments at each planned intersection. Over 1,600 monuments were set, with the intention of being removed (or covered over) when the streets were built.

So then the question became, might some of these monuments remain to this day?

The scope of my physical investigation was limited to those areas that have not been developed in the intervening years. The map of the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 indicated that the land now encompassed by Central Park was, at the time of the survey, intended to be separated into orderly city blocks just like the rest of the city. ((For a critical reading of the New York City Randel survey, Weissman highlights Rose-Redwood’s master’s thesis exploring the “politics of mapping” that the Randel survey represents: in it Rose-Redwood “focuse[s] on the environmental history of New York City, and the changes the grid brought to the city and its inhabitants. To him, these bolts represent the ‘politics of mapping.’ That is, their physical presence meant both a new modern city to Randel and other officials as well as assured destruction to landowners” (Weissman, 2015) as well as other residents. For more see Reuben Skye Rose-Redwood, “Rationalizing the Landscape: Superimposing the Grid Upon the Island of Manhattan” (master’s thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, 2002), and, Cale Weissman, “The Hidden Bolts that Drive Manhattan’s Infrastructure Nerds Nuts,” Atlas Obscura, 28 Sept. 2015, http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-hidden-bolts-that-drive-manhattans-infrastructure-nerds-nuts, accessed 7 Oct. 2016. For more of Rose-Redwood’s related work, see his Google Scholar profile: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=-MZiotMAAAAJ&hl=en. )) This made Central Park a likely candidate for finding an original survey bolt, should any still exist.

Using Google Maps, my husband and I identified a few promising locations in Central Park by working out where the streets and avenues would have intersected had the grid been imposed as planned, and then narrowing down our list to the areas that had exposed bedrock. Then we took a trip to Manhattan to test our idea. The first location didn’t look as we expected it to and we found nothing. But at the second location, protruding about four inches from the bedrock outcrop was a weathered iron bolt!

How could we be sure we had found one of the original bolts? We weren’t 100% certain at the time, but the one inch square bolt with a cross cut in the top matched the description of the bolts set by the Randel survey, and its coordinates matched the expected location of the intersection. In the years since a few of us independently worked out its location, the bolt has seen a lot of interest and discussion in online articles and a few books sparked by interest in the grid. ((Weissman, “The Hidden Bolts.” Richard G., “Randel Survey Markers in New York City Parks,” Papa Bear’s Beyond Central Park, Feb. 2016, http://beyondcentralpark.com/BCPMarkersInNYCParks.php#, accessed 7 Oct. 2016. Rhonda L. Rushing and Angus W. Stocking, Lasting Impressions: A Glimpse into the Legacy of Surveying, Berntsen International, 2006. Marguerite Holloway, The Measure of Manhattan: The Tumultuous Career and Surprising Legacy of John Randel, Jr., Cartographer, Surveyor, Inventor, W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.)) Anyone searching now for this bolt will have an easy time of it.

This particular mark was one of my favorite finds because it encompasses so much of what we’ve been talking about: the importance of infrastructure, the decisions throughout history that formed the landscape we see today, and the use of these fun historical “puzzles” to help develop our research skills and judgment over time!

Donna: As you describe all of this, I am seeing several of the example dispositions for “Research as Inquiry” in action: you “. . . value intellectual curiosity in developing questions and learning new investigative methods; . . . value persistence, adaptability, and flexibility and recognize that ambiguity can benefit the research process; . . . [and] follow ethical and legal guidelines in gathering and using information.” ((Framework, 2015, 2016.)) It seems as though for a challenging recovery like this one, the ability and desire to explore many sources of information through varied methods, and to do so with a sense of respect and responsibility for how you interact with these physical sites and digital/digitized sources, are paramount to the recovery’s success.

Your New York City recovery is also a case study in the close relationship between the “Research as Inquiry” frame and “Searching as Strategic Exploration” frame, where the latter states that “Searching for information is often nonlinear and iterative, requiring the evaluation of a range of information sources and the mental flexibility to pursue alternate avenues as new understanding develops.” ((Ibid.)) Looking at the “Searching as Strategic Exploration” frame in particular, are there other connections between survey mark hunting and information literacy that you became aware of as you read the Framework for our conversation here? In what other ways do you use and develop your own information literacy when you embark on a survey mark recovery?

Jennifer: Given its emphasis on iterative exploration and discovery, with a dash of serendipity, “Searching as Strategic Exploration” struck me as the frame most concretely connected to the steps I take when investigating survey marks. I often browse maps and datasheets for fun, just to see what interesting survey marks might be in a given area, and it may not be until months later that I have the opportunity to search for them.

Assuming I’m planning a physical search, first I identify a target mark. The initial scope might be the area where I’m going to be vacationing. Then I narrow the scope depending on a specific goal or restriction: maybe I’m looking for a mark of particular historical relevance, or one that would be most useful to modern surveyors working on an upcoming highway project. Or I might be looking for an especially challenging mark or a very easy and quick one, depending on how much time I can devote to the search. These categories overlap; very often the marks that are more historically interesting haven’t been recovered in 50 years and are buried beneath decades of accumulated forest debris, while the ones that are more likely to be used in modern highway projects are in easy-to-access public right-of-way along the road shoulder.

The key is to be flexible, and to accumulate useful sources as your experience grows. The NSRS database is the standard starting point, but I always check additional sources, like USGS datasheets (which are only available in paper form) or survey mark logs on Geocaching.com. Next, I’ll plug the mark’s coordinates into Google Maps or Google Earth and have a virtual look around. If a Street View is available, it gives me a relatively recent first-person view of the area—often helpful for determining parking locations or property access. The datasheet description might refer to old roads or railroad tracks that no longer exist. In those cases, I would refer to historical aerial imagery and old topographic maps, also available online or in local archives. At this point, my goal is to have a general idea of a safe place to leave my vehicle, a reasonable approach to the survey mark site, and an estimate of any trouble I might encounter along the way.

Once I’m at the site, however, regardless of preparation, the situation can look drastically different than expected. I’ve had experiences where I had to turn away immediately because of uncooperative landowners, and other experiences where I searched for an hour without finding any sign of the survey mark. I’ve had to return to some sites multiple times armed with new information or new tools before ultimately finding the mark, say, moved from its intended location or buried beneath six inches of dried mud. Still, the more I know about the area and the mark’s history, the more I’m likely to correctly interpret the physical features I see before me.

A theme I noticed running through each frame is the synthesis of critical and creative thinking. We’ve talked in depth about the information that survey marks represent and how it is produced, how both amateurs and professionals are part of the community of people who use and value that information, and of course the importance of creative, iterative searching and discovery. I’m confident in saying that the activity of survey mark hunting both requires and develops information literacy.

Donna: Your process of search and discovery reminds me of an academic researcher mapping their search route through clues found in footnotes and works cited lists, leading them to information located in collections at another site from their current location—right down to researching in advance where to put their vehicle once they get there, if they’re visiting an off site collection! Even including issues of access—“Will I have permission to access (physically/electronically/socially) the site/collection? What permissions and data points do I need to obtain in advance in order to have a successful search once I arrive?”—these processes are so similar.

Their similarity also raises some important questions about privilege and its attendant access to not only information, but the rich learning experiences that develop information literacy as well. For instance, what are the physical, social, and political barriers to information literacy experiences (like survey mark hunting or opportunities to engage in academic research) for those with marginalized identities related to race, gender, sexuality, class, and disability? The Framework acknowledges these barriers to a degree in the “Scholarship as Conversation” and “Information Has Value” frames, ((Ibid.)) but could go farther in articulating ways to mitigate them as critical educators.

You also alluded to the idea that, the more a researcher learns about their subject, the better able they will be to “interpret the […] features” in information sources and discourses that treat on that subject. The importance to information literacy of this constant process of preparation for reading and interpretation cannot be overstated; in fact, the Framework incorporates this idea in its mention of “expertise” throughout the document. ((Ibid.))

You mentioned the synthesis between creative and critical thinking that happens through this activity. As a way to sum up our dialogue, could you describe the effects your participation has had on the way you see and understand the world around you?

Jennifer: There is a real motivational thrill to discovering something previously unknown, at least to myself. I’ve become fluent in the use of so many different types of maps, websites, and databases, and familiar with old technologies and architecture and infrastructure—subject areas that I might never have set out to learn in such depth. But when I’m trying to find that elusive bronze disk that no one has seen in decades I always want to check one more source, learn about one more layer of the history of the place I’m researching. As survey mark hunters, we learn how to determine and how to become authoritative sources of information to others, developing our expertise through the process; how to recognize problems and propose hypotheses; how to test them and try again when we fail; and how to contribute back to the discussion.

Seeing the world through different people’s eyes, through the language they use that reflects the material world and philosophies of their times, has naturally impacted the way I see the world. I appreciate the challenge, sometimes futile, of finding a supposedly stable, permanent mark in a constantly changing world. Set and described with the best intentions of permanence, survey marks may still become victims of progress in far less than a human lifespan. If I’ve learned anything from this activity, above all it’s that everything is temporary, and I’ll enjoy the world around me while I can.

Donna: From accessing, evaluating, using, and contributing to the NSRS survey mark datasheets, to the holistic process involved in exploring multiple sources of data, information, and history about specific survey marks, it is clear that survey mark hunting offers a material embodiment of information literacy in practice. Add to this the fact that it is situated within various overlapping communities of participants and professionals, and the information literacy of survey mark hunting is evident.

Jennifer, thank you so much for contributing your time and expertise by participating in this dialogue. In addition to gaining an in-depth understanding of an activity I knew little about, having this conversation with you has led me to a more concrete understanding of information literacy as articulated by the Framework.

Jennifer: Thank you, Donna, for the chance to share my enthusiasm for survey mark hunting, and to learn so much about the Framework! Like you, I’ve gained a deeper understanding of information literacy by examining my own behaviors and thought processes in the context of the Framework. I hope our conversation inspires others to do the same!

Acknowledgments: Thank you to our reviewers: Nancy Foasberg, whose knowledge of the network of conversations surrounding the topics addressed in this piece was indispensable and enriched the article greatly; and Ian Beilin, whose critical yet generous reading invited us to make this article more inclusive (and thus better) than it would have been otherwise. Thank you also to our publishing editor, Ellie Collier, for shepherding us through the publication process with competence and care, and to the Lead Pipe editorial board for believing in our article idea early in the process. We are also grateful to Richard Galas for his photographs documenting some outstanding survey mark hunting adventures!

Bibliography

“About Survey Mark Hunting.” Zhanna’s SurveyStation. Jennifer Galas/SurveyStation, 2016. https://thesurveystation.com/about-survey-mark-hunting/.

Bishop, Bradley Wade, and Melissa P. Johnston. “Geospatial Thinking of Information Professionals.” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 54.1 (2013): 15-21. ERIC. ED EJ1074098.

Deterding, Sebastian. “Gamification: Designing for Motivation.” Interactions 19.4 (2012): 14-17. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2212877.2212883.

Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Association of College and Research Libraries, 2015, 2016. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework.

Holloway, Marguerite. The Measure of Manhattan: The Tumultuous Career and Surprising Legacy of John Randel, Jr., Cartographer, Surveyor, Inventor. W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

“infrastructure.” Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press, 2016. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/infrastructure.

Kim, Bohyun. “Keeping Up With… Gamification.” Keeping Up With…. Association of College and Research Libraries, May 2013. http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/keeping_up_with/gamification.

Leigh, George E. “Bottles, Pots, & Pans? – Marking the Surveys of the U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey and NOAA.” National Geodetic Survey: History. n.d. http://www.ngs.noaa.gov/web/about_ngs/history/Survey_Mark_Art.pdf.

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Map of the city of New York and island of Manhattan as laid out by the commissioners appointed by the Legislature, April 3, 1807.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-f4dd-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Lloyd, Annemaree. “Informed Bodies: Does the Corporeal Experience Matter to Information Literacy Practice?” In Information Experience: Approaches to Theory and Practice, edited by Christine Bruce, Kate Davis, Hilary Hughes, Helen Partridge, and Ian Stoodley, 85-99. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2014. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/S1876-056220140000010003.

McGonigal, Jane. Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. The Penguin Press, 2011.

Miller, Jason, C. Peter Keller, and Larry D. Yore. “Suggested Geographic Information Literacy for K-12.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 14.4 (2005): 243-250. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10382040508668358.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “Survey Mark Hunting.” National Ocean Service. n.d. http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/for_fun/SurveyMarkHunting.pdf.

Nazari, Maryam. “The actuality of determining information need in geographic information systems and science (GIS): A context-to-concept approach.” Library & Information Science Research 38.2 (2016): 133-147. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2016.04.005.

Nazari, Maryam, and Sheila Webber. “What do the conceptions of geo/spatial information tell us about information literacy?” Journal of Documentation 67.2 (2011): 334-354. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00220411111109502.

Nicholson, Scott. “A RECIPE for Meaningful Gamification.” In Gamification in Education and Business, edited by Torsten Reiners and Lincoln C. Wood, 1-20. Springer International Publishing, 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_1.

Richard G. “Randel Survey Markers in New York City Parks.” Papa Bear’s Beyond Central Park. Feb. 2016, http://beyondcentralpark.com/BCPMarkersInNYCParks.php#.

Rose-Redwood, Reuben Skye. “Rationalizing the Landscape: Superimposing the Grid Upon the Island of Manhattan.” Master’s thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, 2002.

Rushing, Rhonda L., and Angus W. Stocking. Lasting Impressions: A Glimpse into the Legacy of Surveying. Berntsen International, 2006.

Schroeder, Robert. Critical Journeys: How 14 Librarians Came to Embrace Critical Practice. Library Juice Press, 2014.

Smale, Maura A. “Learning Through Quests and Contests: Games in Information Literacy Instruction.” Journal of Library Innovation 2.2 (2011): 36-55. http://www.libraryinnovation.org/article/view/148/238.

Turnbull, David, Helen Watson, and the Yolngu community at Yirrkala. Maps are Territories: Science is an Atlas: a portfolio of exhibits. Inventive Labs, 2008. http://territories.indigenousknowledge.org/home/contents.

U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. The Preservation of Triangulation Station Marks. U.S. Govt. print. off., 1941. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001483918.

Weissman, Cale. “The Hidden Bolts that Drive Manhattan’s Infrastructure Nerds Nuts.” Atlas Obscura. 28 Sept. 2015. http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-hidden-bolts-that-drive-manhattans-infrastructure-nerds-nuts.