Becoming a Writer-Librarian

In Brief: This article offers a reflection on my pursuit to become a writer-librarian. In addition to participating in a professional writing program at my institution, in November of 2012 I participated in Academic Writing Month and Digital Writing Month. Through these immersive experiences I worked to figure out who is my writerly librarian self and discovered some tools and techniques to help me along the way. This article begins with an explanation of Academic Writing Month and Digital Writing Month, discusses writing in Library and Information Science, and then offers more reflection on my discoveries as I tried to become a writer-librarian. Among my discoveries, the most helpful were getting to know my writing barriers and making writing social. Finally, this article offers advice to others who may wish to incorporate writing into their professional lives.

Photo by Flickr user Urbanworkbench (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

by Emily Ford

Introduction

I always tell people that if I hadn’t become a librarian I would have become a chef, but this is a lie. The truth is that I always wanted to be a writer. To be a manipulator of words and to caress them into meaning—this was the thing I wanted, and yet it is the thing that has taken me thirty-three years to publicly admit.

When I had the opportunity to write in my professional life and work with In the Library with the Lead Pipe, there was no decision to be made. Over the past four years I have become immersed in the world of professional writing and editing as a Lead Pipe Co-Founder and Editorial Board member. Writing, as I had always perceived and experienced it, was a lonely task. As a child and teenager I journaled alone. I wrote poems alone. Writing papers throughout the course of my career in higher education as a student and professional had also always been a mostly lonesome task.

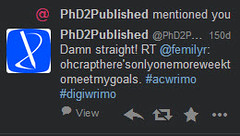

Acwrimo was started in 2011 by Charlotte Frost, founder of PhD2Published, a blog and online community that serves as a resource for “Academic Publishing Advice for First Timers.” For Frost, Acwrimo was a way to kick into gear an academic writing project. Using social media, participants announced their progress, supported other community members, gave advice, and generally participated in a virtual academic writing community. While the goal first posted by Charlotte was to write 50,000 words, it could really be whatever goal you wanted to set for yourself. Similarly, Digiwrimo challenged participants to write 50,000 digital words between November 1st and 30th, but it also challenged participants to think about what it is to write digitally. More structured than Acwrimo, Digiwrimo offered weekly tweet chats and presented participants with opportunities to write creatively and collaboratively on projects. The month also featured a Night of Writing Digitally, wherein its organizers hosted participants at Marylhurst University for a night of writing individually, collaboratively, and yes, digitally.

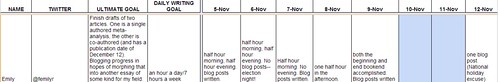

The goals I set for myself were pretty lofty. I set separate goals for both Acwrimo and Digiwrimo, but intentionally overlapped some of them. For Acwrimo I would write an hour a day or seven hours a week, blog the process to the end goal of having a future Lead Pipe article about the experience, and complete a draft of an article I had been working on for eight months. For Digiwrimo I would post once a day at my personal blog, tweet once a day, have drafts of two Lead Pipe articles complete, and have drafted an essay for a non-library publication. Suffice it to say, I did not completely meet any of these goals. Instead, the month became more about the writing process itself. I began to question. What IS it to write? What is it to write digitally? What is it to write librarianly or to be a writerly librarian? As I completed pomodoros and blogged and tweeted, I wanted to know what it is to be a writer and a thinker in the field of LIS.

The rest of this article is my attempt to answer these questions. First I’ll investigate writing in LIS and reflect on my experiences with writing in the field. Then I will reflect on the writing activities I pursued in November. Sharing my insights I will attempt to define what it is to be a writerly librarian and how to become one.

Writing in Library and Information Science

There is no paucity of literature discussing librarians and writing. Blogs, columns, books, and general writing advice is easy to find. In fact, several librarian writers discuss what they see as the natural relationship between librarian-ing and writing. Carol Smallwood discusses her 2010 book, Writing and Publishing: The Librarian’s Handbook, in American Libraries magazine. “Librarians tend to be creative people, and what other profession than librarianship could be more encouraging for writers? We are surrounded by books, technology, and people, providing the opportunity not only to write for the profession but also to produce poetry, novels, short stories, and creative nonfiction for children and adults” (Smallwood, 2009). Indeed, there are numerous examples of librarians who author short stories, mystery and romance novels, poetry and more poetry, and even those who have authored biographies for an audience of juveniles.

Creative pursuits aside, there is also a vast realm of professional literature in librarianship. Writing in professional literature is dominated by library school faculty and academic librarians (Penta & McKenzie, 2013). Even for these professionals writing can be a struggle. Almost all of the existing articles and columns discussing writing librarians address the challenges of hectic and busy work lives. Moreover, much of the writing activity in librarianship occurs outside of the normal working hours; it is treated as extracurricular.

“Writing is generally done outside the “normal” working day; frequently, they do not work in a culture where the dissemination of practice and research output is the norm; librarians may have a clear sense of identity of themselves as practitioners supporting the publishing efforts of their academic colleagues, rather than as active participants in generating scholarly output.” (p. 8, Fallon, 2012)

In their 2010 article, “Beliefs, Attitudes, and Perceptions about Research and Practice in a Professional Field,” Jane Klobas and Laurel Clyde present lack of time as one of the most common barriers to writing for library practitioners. It is probably for this reason that many practicing librarians choose not to make writing a priority in their careers, especially if writing is not required in their jobs.

However, writing does more for librarianship than take up spare time. In her 2008 editorial published in College &Undergraduate Libraries, Inga Barnello acknowledges a universal lack of writing time in librarianship, but argues that by sharing and disseminating our work, we librarians work to support one another: “We are all swamped. Those who are writing do not have some bank of free time from which to withdraw extra hours in the day for writing. Secondly, we have similar issues that we are grappling with. Our projects revolve around common predicaments. We all benefit from the best practices of others” (p. 73). For Barnello writing and disseminating our work means that others don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

Like Barnello I see writing as an essential part of communicating with my colleagues. I also fall into the extracurricular “weekend writer” camp—these Lead Pipe articles don’t write themselves!—my writing activities extend far beyond my working hours. For someone like me, not writing is not an option; I am intellectually curious and attempt to engage in a reflective praxis of librarianship. Writing manifests as an excellent tool to engage in my praxis.

I’m No Expert

I may be a co-founder and editorial board member for Lead Pipe, but I am by no means an expert writer. I served a stint as a co-editor of RUSA Update, but most of my scholarship and professional writing experiences to date have been connected to this journal. This is not to say that Lead Pipe hasn’t been an incredible and educational experience. In fact, current and former Lead Pipe Editorial Board members are some of the best (and harshest!) editors I’ve ever had, and each author for Lead Pipe writes with her own panache. I think about our writing in LIS, and I think about what we do and what we are required to do, and how we must be increasingly proficient with different writing modalities to be successful and good at our jobs.

No one is born a writer. Sure, individuals may show a certain aptitude for language and the written word, but no one automatically knows how to do it. Like anything else it takes practice, time and dedication. Still, how are we librarians trained to write? Do librarians learn to write in library school? I didn’t. I started the process in 1st grade when my teacher insisted that we all keep journals. Continuing throughout my K-12 education there were a handful of teachers who instilled in me good writing practices and skills. Ms. Moulden in the 1st grade—I still have my journals—Mrs. Baldwin in the 4th grade, Mrs. Walkiewicz throughout high school, Dr. Pancho Savery in college—who taught me proper use of “that” and “which”—and Dr. Katja Garloff, my senior thesis adviser. By the time I reached graduate school I had a solid writing foundation. Luckily, I found a good editor in Phil Eskew, an adjunct professor who taught my first-ever library school class: Issues in Public Library Management. He asked that we write several two-page papers. Two pages! As one who studied German literature in college I was accustomed to the twenty-page academic paper. Two pages! Obviously writing as a librarian would be incredibly different than my senior thesis, and it would pose unique challenges. I had to learn to write clearly and succinctly.

As librarians we are asked to write daily. Whether it’s email with students and faculty answering questions and explaining policies and procedures, or whether it’s short announcements about programs and services, we arguably communicate more today via the written word than ever before. Moreover, our professional associations and recent practice in librarianship has moved toward the trend for us to “articulate our value.” (ACRL’s Value of Academic Libraries initiative, the NN/LM Middle Atlantic Region Study, and I Love Libraries’ Library Value Calculator are a few good examples.) There is no better way to articulate value than to communicate it through words. The excessive amounts of data we gather is not enough. It is the compelling stories behind the data that we need to communicate—and with good writing this articulation becomes easier.

Writing is Social

A month prior to starting Acwrimo and Digiwrimo I began participating in a year-long writing program at my institution called Jumpstart Academic Writing. The program, facilitated by Dannelle D. Stevens, PhD, put participants into writing groups that were asked to meet weekly. The writing groups were intended to bring a social aspect to writing. Group members announced to one another their weekly writing goals. In this group participants were individuals one could ask for help, or they could simply act as peer mentors who held one another accountable for their goals. Each month the program hosted a larger group meeting facilitated by Dr. Stevens. In these meetings she led us in writing activities that encouraged us to become more familiar with our writing selves and the practice of academic writing and publishing.

During November a typical writing day for me began while I drank my coffee and ate my breakfast. I caught up on #acwrimo and #digiwrimo tweets, blog posts and other social media items that had accumulated overnight and early in the morning from the East coasters, European and Australian participants. After getting to work I would boot up my machine, make some tea, close my office door and sit down to complete one writing pomodoro. ((During this time I was working on both a literature review article that will be forthcoming this summer provided the publisher and I get the author agreement worked out, and the article Carol Bean and I published in December: “Open Ethos Publishing at Code4Lib Journal and In the Library with the Lead Pipe.”)) I wrote “offline”—no Facebook, email, Twitter or any other potential distraction. After my 30 minutes ended I would go about my work day, periodically checking in on the #acwrimo and #digiwrimo Twitter streams. If it was a Thursday, I would meet with my writing group at noon, where we would eat lunch and check in on each others’ progress. When 5:30 rolled around I would stop whatever I was doing, log out of email, and shut my office door. Again opening one of my writing projects I would complete one more pomodoro before leaving work.

After some downtime and dinner I returned to writing immersion. If there was a Digiwrimo challenge, I would attempt to participate. Evenings were also my designated time to reflect on writing successes and challenges (in blog form), and the time during which I attempted to craft words into sentences and paragraphs on my personal blog. Before the night ended I would be sure to log the day’s productivity on the public Academic Writing Accountability Google Doc.

As a result of November and my participation in the Jumpstart Writing Program [pdf] I realized that, in contrast to my previous reclusive writing behavior, my writing was becoming and should be social. I was better able to keep up with my seven hour a week goal when I tracked my progress on a public spreadsheet; I was better able to keep my writing time focused when I publicly declared goals to peers in my writing group; and I was able to get help and support for writing when I asked my community for it and when I saw others in my community struggling with similar writing obstacles.

The main differences between the virtual writing months and the Jumpstart Writing Program were a matter of intensity. In the Jumpstart program participants focused on small, achievable goals—with the end goal that participants would build a sustainable writing practice to continue throughout their professional lives. In wild contrast, Acwrimo and Digiwrimo focused on grand plans and some rather insane goals, projects and schemes. As the folks over at ProfHacker stated, the first rule of Acwrimo is to “set yourself some crazy goals.” Similarly, Digiwrimo encouraged participants to count every word written in emails, tweets, and Facebook updates and comments. The Digiwrimo About page declared: “Digital Writing Month is a (somewhat) insane month-long writing challenge, a wild ride through the world of digital writing, wherein those daring enough to participate wield keyboard and cursor to create 50,000 words of digital writing in the thirty short days of November” (Digital Writing Month, 2012). In fact, Digiwrimo began November 1st with a challenge for participants to collaboratively write a novel in a day.

I decided to participate in Acwrimo and Digiwrimo to immerse myself in writing and to think differently about writing. The in-person program in which I was participating was great, but I felt like I needed an intense writing boot camp to complete some projects. Plus, the prospect of thinking about writing in new ways, as promised by Digiwrimo, appealed to me. During this month I was going to be the lone wolf; the writer who holed herself up in her office pretending she wasn’t in the building during the first and last half hours of the day. When I would get home from work I would continue writing. Yes, my goals were insane—of course I did not fully meet any of them—but I did not let that discourage me. What I did not expect to uncover during November was how social I was becoming in this writing process that had previously seemed a lonesome endeavor.

Digiwrimo, in particular, was structured to be collaborative and social. Its organizers invited writers to create crowdsourced poems, novels, and other creative written works. During the Night of Writing Digitally, an in person and virtual event, we wrote a poem, and the month ended with a beautiful Twitter Essay. (You can still read it, thanks to this Storify by fellow Digiwrimo participant, Kevin Hodgson. In fact, you can get a glimpse into Digiwrimo at the Digiwrimo Scoop.it page.)

Using social media I was able to check in with my writing colleagues across the globe, offer encouragement to those who were struggling, and seek similar encouragement when I needed it. My contributions to the Academic Writing Accountability Google Doc, too, were evidence of my social writing behavior. But it wasn’t just my behavior. These writing communities were inherently social. They were communities of practice with all of the necessary parts. ((“The community of practice is, then, the group of practitioners with whom learners must engage and in whose activities they must be able to participate in order to learn. Learning is, ultimately, the process of becoming (and becoming recognized as) a member of such a community. As such, learning involves much more than acquiring the explicit knowledge associated with a particular practice. It also requires developing the tacit understanding, inherent judgment, and shared identity that come with participation.” (Duguid, 2003, p. 234) )) I learned, engaged, and identified as an Acwrimo-er and a Digiwrimo-er, and I still do.

Reflecting on Writing

But it wasn’t just these programs that allowed me to discover my writerly self, on my own I began to read about writing. One of the books I had heard recommended by Dr. Stevens and fellow junior faculty members was Paul Silvia’s How to Write a Lot. Certainly aimed at academics who need to try to incorporate writing into their daily routines, Silvia’s book is startlingly easy to read, insightful, and humorous.

Of course it is a misconception that academic writing must be dry, nap-inducing, third-person reports of research written for journals whose editors will suck the life out of your work. And no one better communicates this than Paul Silvia. His short monograph allows readers to enter into his world—one of a prolific academic writer. He is a psychologist who constructs beautiful, engaging and witty sentences. On my Acwrimo blog, Seven Hours a Week, I wrote:

“Now halfway through this book, I’ve noticed that several chapter begins with unexpected similes, or at least witty and surprising statements. For instance, chapter two begins with, “Writing is grim business, much like repairing a sewer or running a mortuary.” Chapter four: “Complaining is an academic’s birthright.” Chapter six: “Psychology journals are like the mean jocks and aloof rich girls in every 1980s high school movie–they reject all but the beautiful and persistent.” Silvia’s discussions of grammar and punctuation utilize subtle and elegant examples, embedded almost secretly within the text; it is almost as if he is amusing himself. I congratulated myself on noticing this brilliant execution, and also found myself wondering if he intended to offer us that reward of self-gratification.”

Silvia inspired me to make the time to write. I had to face it, I was not going to be struck by a moment of passion in which I had to drop everything I was doing and write an article about librarianship. Instead of allowing a looming deadline to inspire me, I took Silvia’s advice and put aside the first and last half hour of my working day to write.

One of the activities I completed in the Jumpstart Writing Program was based on a book by Robert Boice, Professors as Writers. He created an instrument to allow academic writers to better know themselves—the blocking questionnaire. Questions Boice asks are those related to our inner thoughts and about writing and our writing habits. He breaks blocking down into seven components: work apprehension, procrastination, writing apprehension, dysphoria, impatience, perfectionism, and rules. From there he organizes these seven categories into three different measures: checklist for overt signs of blocking, checklist of cognition/emotion in blocking, and survey of social skills in writing. A writer can score herself in each of these measures, and then compute her mean blocking score and her mean component scores to see where are her blocks and what are her traits. Based on the questionnaire I discovered that I am an impatient perfectionist – a writer full of contradiction. Although these traits aren’t secret to me, the questionnaire allowed me recognized them in their brutal and ugly honesty.

Impatience is pretty straightforward and so is perfectionism. However, when reading the description of perfectionism I was taken aback.

A few writers, in my experience, refuse to abandon their maladaptive styles of perfectionism, supposing that doing so is tantamount to abandoning civilized standards of excellence. In this regard, perfectionism resembles shyness in that its possessors tend to be nice people who are closet elitists. (p. 153)

My inner dialog huffily reacted, “I am NOT an elitist!” A few moments later it resigned. “Crap. I’ve been outed.” Since I began my career I edited others’ works, received feedback on my writing, and wrote collaboratively. Yet how is it that I was now a closet elitist? Reflection and self-discovery were not foreign to me and I embraced any exercise that allowed me to acknowledge and better understand myself and my writing practice. Simply by discovering my writing blocks, I took a step towards ameliorating them.

It Wasn’t All Reflection

Even though I didn’t fully meet my goals, my Acwrimo and Digiwrimo 2012 were incredibly productive. During the month I completed, with my co-author Carol Bean, “Open Ethos Publishing at Code4Lib Journal and In the Library with the Lead Pipe.” I had a draft of a research article completed, which I was then able to whip into shape and submit by mid-January. Moreover, a co-author and I received revision requests for a book chapter during this month, which we were able to quickly turn around and resubmit to the editor.

What I noticed about my technique, opening and ending my work day with a half hour pomodoro ((The Pomodoro Technique is a method of time management wherein one concentrates on a task, typically for twenty-five minutes, and then takes a five minute break. After four pomodoros, as these twenty-five minute chunks of time are popularly called, one takes a longer break.)) of writing time, is that it was a great way to get some of the nitty-gritty writing work out of the way. A half hour allowed me to freely write, and it allowed me to poke at revisions and edits. But I also sometimes felt that these half hours were lacking. At the end of some of these half hours I felt like I had just gotten started, and so I would extend my time by five or ten minutes, or even for another half hour. However, I frequently did not have the leeway in my schedule to do so, nor did I feel that I could ignore all of the other things that were piling up while I was spending time writing.

Despite my ability to set aside work-day time for writing, a lot of my Acwrimo and Digiwrimo writing activity occurred “off the clock.” It was on weekends when my co-author and I could connect via Google+ hangouts, and when I had longer than half-hour chunks of quiet time to edit and revise my work. At the end of it all, I feel most proud of the Lead Pipe articles that were partially drafted during Acwrimo and Digiwrimo. For the most part, this is because I like the content and subjects of what I write for Lead Pipe. I also feel more free and confident when writing for Lead Pipe than for other venues. Here I have a voice and here I have an established writing community of practice.

All in all, November 2012 was a productive writing month for me. In addition to the self-reflection and self-discovery I began to produce a body of work that has culminated in works that have already been published or will be published in the future.

Find Your Writerly Self and Become a Writer-Librarian

In the past my writing had always been a solitary activity. But as a result of my participation in Acwrimo, Digiwrimo, and in the Jumpstart group, I have come to better know my writerly librarian self. I am an impatient perfectionist. I am prone to holing up in my home office on Saturday mornings or spending $3.50 on a decaf rice milk latte and three hours producing sentences and paragraphs that hopefully mean something. But I also need to be part of a social writing community; my best writerly self emerges when I am part of a community of practice. Keeping writing social allows me to set and attain goals and allows me to get necessary feedback earlier in the writing process. Discovering these things was tough, but even though acknowledging my personal challenges was intimidating, the rewards have made it worth the effort.

For you readers who would like to discover your writerly librarian selves, there are a few things I’ve gleaned from my immersive experience that I encourage you to do. First, get to know your librarian self. What do you value? What is your philosophy? What do you have to share? What do you want to share? Then get to know your writerly self. What are your writing challenges and what are your writing behaviors? Consider checking out Boice’s book and take the blocking questionnaire. After you’ve identified your blocks, think about how you can work with them. What can you do to overcome the impatient perfectionist in you? Knowing what are your challenges will enable you to better operate with them. For me, I am now trying to work well in advance of deadlines to tame the impatience (I can deal with a deadline), but also to allow myself enough time to polish my work before it gets published.

After you’ve engaged in some writerly self-discovery, try to think about how you want to prioritize writing as part of your life. Will it be on weekends? Will it be every morning? In essence, what will you sacrifice in order to write? As you begin to incorporate writing into your professional life, be sure that you allocate the time to do so. Be aware that when you allocate time to write, you will be taking time away from other tasks. Think about whether there is something on your plate that you don’t need to do, or you can do less frequently, or if it is something that can be delegated to someone else.

When you’ve come to know yourself and when you’ve set aside the necessary time, next try to set some writing goals. Set short-term goals—these can be weekly or daily—and set some long-term goals. Your goals should be a mix of easily achievable and those that would be more challenging. And whatever goals you do set, go easy on yourself. It’s not whether you achieve them, it’s the ride you take to try and get there.

Finally, make writing social. Find an existing writing community of practice like Acwrimo and participate. You can even start tracking your progress on the publicly shared Academic Writing Accountability spreadsheet. Alternatively, you can form your own writing group. Whatever you do, find or create a community—be it virtual or face-to-face—that challenges and supports you to become not only your writerly self, but a writer-librarian.

Many thanks to Chris Hollister and Emily Drabinski for their thoughtful comments and feedback. Additional thanks to Lead Pipe Editorial Board members Erin Dorney and Ellie Collier for their comments and edits.

Nice article! How long does it take to finish an article like this on average?

thanks! I’m not really sure I know the answer to your question because I’ve never quantified it. Usually I have spent a while fleshing out my ideas during my commute to and from work, while walking, etc. Then I’ll try to wrangle with my argument or the article’s purpose. This all happens before I even get my fingers to the keyboard to write.

My next step in the process is to try and create a sensible outline for an article. Usually I share the outline–and frequently the prior thinking process about an article topic–with with colleagues and friends. (This is a great example of writing as a social activity.)

When I get to the point where I am ready to write from an outline, I can draft an article fairly quickly–say, 3-4 hours of work–but sometimes it takes much longer if I am still grappling with my argument or ideas. Then, of course, there is the editing process. Typically I will edit first, then share with a colleague, and edit some more. Then there is the peer-review process, more editing and revisions.

I guess if you really want a ball park figure of how long it takes me to write one Lead Pipe article (as in, working at the keyboard) I’d say 10 hours? But that is so hard to quantify and really doesn’t mean anything.

Ideas sometimes float around in my brain for several months before I get to the point of even being able to talk to someone about them. In short, writing is not only about the time I spend at the keyboard, but on my personal reflections and the time I spend thinking about what I’m going to write and what I’m going to say. Now that this article has been published I’ve already started thinking about what topic my next Lead Pipe article will tackle.

Always drawn to pieces such as this. I don’t write but desperately want to. I think you accurately portray the level of commitment and effort involved in being/becoming a writer. And as for our profession I like to think it is essential that we make a commitment to this craft. Also your absolutely correct that writing is an integral function of who we are and what we do, so it therefore behooves us practice this craft.

This piece is very motivating and in time I hope to put some of your recommendations into practice.

Thanks for the thoughts

Pingback : On Librarians Writing | Academic Librarian

Pingback : Writing is Social | Thinking Outside the Books

Emily, this is a great article, full of useful details and thoughtful reflection! When something like #digiwrimo is not running, where do you find the best community for this type of writing?

Great question, Celia! There are a few ways that I find community. First, I am in some writing groups at my job. One is still with the Jumpstart Academic Writing program, where I have connected with some colleagues who can help me feel accountable for my writing goals. The other is organized within my library, but is really more of a research group. We talk about our research and writing and set bi-weekly goals.

I’ll also say that just because it’s not November, does not mean that there isn’t a writing community on Twitter. In fact, there is a hashtag for #acwri, which I follow. Also, the public Acwrimo spreadsheet is still active, even though it’s not November. It may take a little more legwork to find a community when it’s not a designated writing month, but they communities are there.

Pingback : On Librarians Writing | Academic Librarian