Adopting the Educator’s Mindset: Charting New Paths in Curriculum and Assessment Mapping

Throwback Thursday for June 18, 2015: In the Library with the Lead Pipe welcomes Bethany Messersmith to our Editorial Board! In honor of Throwback Thursday, we’re highlighting Bethany’s recent piece on curriculum and assessment mapping.

Photo by Flickr user MontyAustin (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In Brief:

The greatest challenge that I faced in my role as Information Literacy Librarian occurred as a result of a Higher Learning Commission (HLC) initiative at my institution, requiring all academic programs/departments to create/review/revise program-level student learning outcomes (PLSLOs), curriculum maps, and assessment maps. This initiative served as a catalyst for the information literacy program, prompting me to seek advice from faculty in the Education Department at Southwest Baptist University (SBU), who were more familiar with educational theory and curriculum/assessment mapping methods. In an effort to accurately reflect the University Libraries’ impact on student learning inside and outside of the classroom, I looked for ways to display this visually. The resulting assessment map included classes the faculty and I could readily assess, as well as an evaluation of statistics on library services and resources that also impact student learning, such as data from LibGuide and database usage, reference transactions, interlibrary loans, course reserves, annual gate count trends, the biennial student library survey, and website usability testing.

Embarking on a Career in Information Literacy

Like most academic librarians there was little focus on instruction in my graduate school curriculum. My only experience with classroom instruction occurred over a semester-long internship, during which I taught less than a handful of information literacy sessions. Although I attended ACRL’s Immersion-Teacher Track Conference as a new librarian, I was at a loss as to how I should strategically apply the instruction and assessment best practices gleaned during that experience to the environment in which I found myself.

When I embraced the role of Information Literacy Librarian at Southwest Baptist University (SBU) Libraries in 2011, I joined a faculty of six other librarians. The year I started, the University Libraries transitioned to a liaison model, with six of the seven librarians, excluding the Library Dean, providing instruction for each of the academic colleges represented at the University. Prior to this point, one librarian provided the majority of instruction across all academic disciplines. As the Information Literacy Librarian, I was given the challenge of directing all instruction and assessment efforts on behalf of the University Libraries. Although my predecessor developed an information literacy plan, the Library Dean asked me to create a plan that spanned the curriculum.

Charting A New Course

The greatest challenge that I faced in my role as Information Literacy Librarian occurred as a result of a Higher Learning Commission (HLC) initiative at my institution, requiring all academic programs/departments to create/review/revise program-level student learning outcomes (PLSLOs), curriculum maps, and assessment maps. I found assessment mapping particularly nebulous, since the librarians at my institution do not teach semester long classes. In lieu of this, I looked for new ways to document and assess the University Libraries’ impact on student learning not only inside, but outside of the classroom setting. The resulting assessment map included classes faculty and I could readily assess, as well as an evaluation of statistics on library services and resources that also impact student learning, such as data from LibGuide and database usage, reference transactions, interlibrary loans, course reserves, annual gate count trends, the biennial student library survey, and website usability testing.

As is the case when discovering all uncharted territories, taking a new approach required me to seek counsel from Communities of Practice at my institution, defined as “staff bound together by common interests and a passion for a cause, and who continually interact. Communities are sometimes formed within the one organisation, and sometimes across many organisations. They are often informal, with fluctuating membership and people can belong to more than one community at a time” (Mitchell 5). At SBU, I forged a Community of Practice with faculty in the Education Department, with whom I could meet, as needed, to discuss how the University Libraries could most effectively represent its impact on student learning.

Learning Theory: A Framework for Information Literacy, Instruction, & Assessment

Within the library literature educational and instructional design theorists are frequently cited. Instructional theorists have significantly shaped my pedagogy over the past three and a half years. In their book, Understanding by Design, educators Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe point out the importance of developing a cohesive plan that serves as a compass for learning initiatives. They write: “Teachers are designers. An essential act of our profession is the crafting of curriculum and learning experiences to meet specified purposes. We are also designers of assessments to diagnose student needs to guide our teaching and to enable us, our students, and others (parents and administrators) to determine whether we have achieved our goals” (13). They propose that curriculum designers embrace the following strategic sequence in order to achieve successful learning experiences – 1. “Identify desired results,” 2. “Determine acceptable evidence,” and 3. “Plan learning experiences and instruction” (Wiggins and McTighe 18).

As librarians, we are not only interested in our students’ ability to utilize traditional information literacy skill sets, but we also have a vested interest in scaffolding “critical information literacy,” skills which “differs from standard definitions of information literacy (ex: the ability to find, use, and analyze information) in that it takes into consideration the social, political, economic, and corporate systems that have power and influence over information production, dissemination, access, and consumption” (Gregory and Higgins 4). The time that we spend with students is limited, since many information literacy librarians do not teach semester-long classes nor do we meet each student who steps foot on our campuses. However, as McCook and Phenix point out, awakening critical literacy skills is essential to “the survival of the human spirit” (qtd. in Gregory and Higgins 2). Therefore, librarians must look for ways to invest in cultivating students’ literacy beyond the traditional four walls of the classroom.

Librarians and other teaching faculty recognize that “Students need the ability to think out of the box, to find innovative solutions to looming problems…” (Levine 165). In his book, Generation on a Tightrope: A Portrait of Today’s College Student, Arthur Levine notes that the opportunity academics have to cultivate students’ intellect is greatest during the undergraduate years. While some of them may choose to pursue graduate-level degrees later on, at this point their primary objective will be to obtain ‘just in time education’ at the point of need (165). It is this fact that continues to inspire an urgency in our approaches to information literacy education.

One of the most challenging aspects of pedagogy is that it is messy. While educators are planners, learning and assessment is by no means something that can be wrapped up and decked out with a beautiful bow. Education requires us to give of ourselves, assess what does and does not work for our students and then make modifications as a result. According to educator Rick Reiss, while students are adept at accessing information via the internet, “Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge present the core challenges of higher learning” (n. pag.). Acquiring new knowledge requires us to grapple with preconceived notions and to realize that not everything is black and white. Despite the messy process in which I found myself immersed, knowledge gleaned from educational and instructional theorists began to bring order to the curriculum and assessment mapping process.

Eureka Moments in Higher Education: Seeing Through a New Lens for the First Time

Eureka moments are integral to the world of education and often consist of a revelation or intellectual discovery. This concept is best depicted in the story of a Greek by the name of Archimedes. Archimedes was tasked by the king of his time with determining whether or not some local tradesmen had crafted a crown out of pure gold or substituted some of the precious metal with a less valuable material like silver to make a surplus on the project at hand (Perkins 6). As water began flowing out of the tub, legend has it that “In a flash, Archimedes discovered his answer: His body displaced an equal volume of water. Likewise, by immersing the crown in water, Archimedes could determine its volume and compare that with the volume of an equal weight of gold” (Perkins 7). He quickly emerged from the tub naked and ran across town announcing his discovery. Although we have all experienced Eureka moments to some extent or another, not all of them are as dramatically apparent as Archimedes’s discovery.

In his book entitled Archimedes’ Bathtub: The Art and Logic of Breakthrough Thinking, David Perkins uses the the phrase “cognitive snap,” to illustrate a breakthrough that comes suddenly, much like Archimedes’s Eureka moment (10). Although the gestational period before my cognitive snap was almost three and a half years in the making, when I finally began to grasp and apply learning theory to the development of PLSLOs, curriculum, and assessment maps, I knew that it was the dawning of a new Eureka era for me.

Librarians play a fundamental role in facilitating cognitive snaps among the non-library faculty that they partner with in the classroom. Professors of education, history, computer science, etc. enlighten their students to subject-specific knowledge, while librarians have conveyed the value of incorporating information literacy components into the curriculum via the Association of College and Research Libraries’ (ACRL) – Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. Now, through the more recently modified Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education, librarians are establishing their own subject-specific approach to information literacy that brings “cognitive snaps” related to the research process into the same realm as disciplinary knowledge (“Information Literacy Competency Standards”; “Framework for Information Literacy”).

Like most universities, each academic college at SBU is comprised of multiple departments, with each consisting of a department chair. The University Libraries is somewhat unique within this framework, in that it is not classified as an academic college, nor does it consist of multiple departments. In 2013, the Library Dean asked me to assume the role of department chair for the University Libraries, because he wanted me to attend the Department Chair Workshops led by the Assessment Academy Team (comprised of the Associate Provost for Teaching and Learning and designated faculty across the curriculum) at SBU. These workshops took place from January 2013 through August 2014. All Department Chairs were invited to participate in four workshops geared towards helping faculty across the University review, revise, and /or create PLSLOs, curriculum, and assessment maps. While my review of educational theory and best practices certainly laid a framework for the evolving information literacy program at SBU, it was during this period that I began charting a new course, as I applied the concepts gleaned during these workshops to the curriculum and assessment maps that I designed for the University Libraries.

What I Learned About the Relationship Between Curriculum & Assessment Mapping

In conversations with Assessment Academy Team members currently serving in the Education Department, I slowly adopted an educator’s lens through which to view these processes. Prior to this point, my knowledge of PLSLOs and curriculum mapping came from the library and education literature that I read. Dialogues with practitioners in the Education Department at my campus slowly enabled me to address teaching and assessment from a pedagogical standpoint, employing educational best practices.

Educator Heidi Hayes-Jacobs believes that mapping is key to the education process. She writes: “Success in a mapping program is defined by two specific outcomes: measurable improvement in student performance in the targeted areas and the institutionalization of mapping as a process for ongoing curriculum and assessment review” (Getting Results with Curriculum Mapping 2). While Hayes-Jacobs’s expertise is in curriculum mapping within the K-12 school system, the principles that she advances apply to higher education, as well as information literacy. She writes about the gaps that often exist as a result of teachers residing in different buildings or teaching students at different levels of the educational spectrum, for example the elementary, middle school, or high school levels (Mapping the Big Picture 3). The mapping process establishes greater transparency and awareness of what is taught across the curriculum and establishes accountability, in spite of the fact that teachers, professors, or librarians might not interact on a daily or monthly basis. It provides a structure for assessment mapping because all of these groups must not only evaluate what they are teaching, but whether or not students are grasping PLSLOs.

Curriculum Maps Are Just a Stepping Stone: Assessment Mapping for the Faint of Heart

When I assumed the role of Information Literacy Librarian at SBU, I knew nothing about assessment. Sure, I knew how to define it and I was familiar with being on the receiving end as a student, but frankly as a new librarian it scared me. Perhaps that is because I saw it as a solo effort that would most likely not provide a good return on my investment. I quickly realized, however, that facilitating assessment opportunities was critical because I wanted to cultivate Eureka moments for my students. In the event that students do not understand something, it is my job to look for strategies to address the gap in their knowledge and scaffold the learning process.

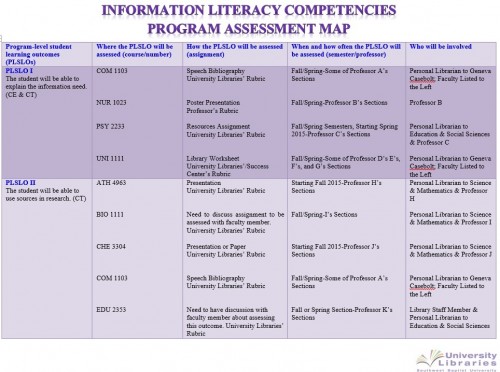

Assessment mapping is the next logical step in the mapping process. While curriculum maps give us the opportunity to display the PLSLOs integrated across the curriculum, assessment maps document the tools and assignments that we will utilize to determine whether or not our students have grasped designated learning outcomes. Curriculum and assessment maps do not require input from one person, but rather collaboration among faculty. According Dr. Debra Gilchrist, Vice President for Learning and Student Success at Pierce College, “Assessment is a thoughtful and intentional process by which faculty and administrators collectively, as a community of learners, derive meaning and take action to improve. It is driven by the intrinsic motivation to improve as teachers, and we have learned that, just like the students in our classes, we get better at this process the more we actively engage it” (72). Assessment is not about the data, but strategically getting better at what we do (Gilchrist 76).

Utilizing the Educator’s Lens to Develop Meaningful Curriculum & Assessment Maps

Over the last three and a half years I have learned a great deal about applying the educator’s lens to information literacy. It has made a difference not only in the way I teach and plan, but in the collaboration that I facilitate among the library faculty at my institution who also visit the classroom regularly. Perhaps what scared me the most about assessment initially was my desire to achieve perfection in the classroom, a concept that is completely uncharacteristic of education. I combated this looming fear by immersing myself in pedagogy and asking faculty in the Education Department at SBU endless questions about their own experiences with assessment. The more I read and conversed on the topic, the more I realized that assessment is always evolving. It does not matter how many semesters a professor has taught a class, there is always room for improvement. It was then that I could boldly embrace assessment, knowing that it was messy, but was important to making improvements in the way my colleagues and I conveyed PLSLOs and scaffolded student learning moving forward. In their article “Guiding Questions for Assessing Information Literacy in Higher Education,” Megan Oakleaf and Neal Kaske write: “Practicing continuous assessment allows librarians to ‘get started’ with assessment rather than waiting to ‘get it perfect.’ Each repetition of the assessment cycle allows librarians to adjust learning goals and outcomes, vary instructional strategies, experiment with different assessment of methods, and improve over time” (283).

The biggest challenge for librarians interested in implementing curriculum and assessment maps at their institutions stems from the fact that we often do not have the opportunity to interact with students like the average professor, who meets with a class for nearly four consecutive months a semester and provides feedback through regular assessments and grades. The majority of librarians teach one-shot information literacy sessions. So, what is the most practical way to visually represent librarians’ influence over student learning? I would like to advocate for a new approach, which may be unpopular among some in my field and readily embraced by others. It is a customized approach to curriculum and assessment mapping, which was suggested by faculty in the Education Department at my institution.

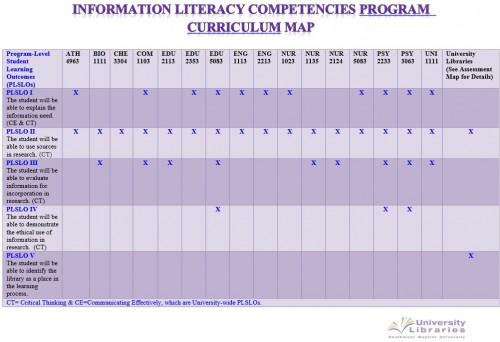

A typical curriculum map contains PLSLOs for designated programs, along with course numbers/titles, and boxes where you can designate whether a skill set was introduced (i), reinforced (r), or mastered (m) (“Create a Curriculum Map”). For traditional academic departments, there is an opportunity to build on skill sets through a series of required courses. For academic libraries, however, it is difficult to subscribe to the standard curriculum mapping schema because librarians do not always have the opportunity to impact student learning beyond general education classes and a few major-specific courses. This leads to an uneven representation of information literacy across the curriculum. As a result, it is often more efficient to use an “x” instead to denote a program-level student learning outcome for which the library is responsible, rather than utilizing three progressive symbols.

One of the reasons why curriculum and assessment mapping at my academic library is becoming increasingly valuable, is largely due to the fact that administrators at my institution are interested in fostering a greater deal of accountability in the learning process, namely because of an upcoming HLC visit. In her article entitled, “Assessing Your Program-Level Assessment Plan,” Susan Hatfield, Professor of Communication Studies at Winona State University writes: “Assessment needs to be actively supported at the top levels of administration. Otherwise, it is going to be difficult (if not impossible) to get an assessment initiative off the ground. Faculty listen carefully to what administrators say – and don’t say. Even with some staff support, assessment is unlikely to be taken seriously until administrators get on board” (2). In his chapter entitled “Rhetoric Versus Reality: A Faculty Perspective on Information Literacy Instruction,” Arthur Sterngold embraces the view that “For [information literacy (IL)] to be effective…it must be firmly embedded in an institution’s academic curriculum and…the faculty should assume the lead responsibility for developing and delivering IL instruction (85). He believes that librarians should “serve more as consultants to the faculty than as direct providers of IL instruction” (Sterngold 85).

To some extent, I acknowledge the value of Hatfield’s and Sterngold’s views on the importance of administration-driven and faculty led assessment initiatives in the realm of assessment. Campus-wide discussions and initiatives centered around this subject stimulate collaboration among interdisciplinary faculty who would not otherwise meet outside of an established structure. As a librarian and member of the faculty at my institution, their stance on assessment creates some internal tension. While it is ideal for our administrations to care about the issues that are closest to their faculty’s hearts, many times they are driven to lead assessment efforts as a result of an impending accreditation visit (Gilchrist 71; Hatfield 5). While I would love to say that information literacy matters to my administration just as much as it does to me, this is an unrealistic viewpoint. The development, assessment, and day-to-day oversight of information literacy is an uphill battle that requires me to take the lead. My library faculty and I must establish value for our information literacy program among the faculty that we partner with on a daily basis. So, how do we as librarians assess the University Libraries’ impact on student learning when information literacy sessions are unevenly represented across the curriculum? In a conversation with a colleague in the Education Department, I was encouraged to determine and assess all forms of learning that the library facilitates by nature of its multidisciplinary role. In Brenda H. Manning and Beverly D. Payne’s article “A Vygotskian-Based Theory of Teacher Cognition: Toward the Acquisition of Mental Reflection and Self-Regulation,” they write:

Because of the spiral restructuring of knowledge, based on the history of each individual as he or she remembers it, a sociohistorical/cultural orientation may be very appropriate to the unique growth and development of each teaching professional. Such a theory in Vygotsky’s sociohistorical explanation for the development of the mind. In other words, the life history of preservice teachers is an important predictor of how they will interpret what it is that we are providing in teacher preparation programs (362).

My colleague in the Education Department challenged me to think about the multiple points of contact that students have with the library, outside of the one-shot information literacy session and include those in our assessment.

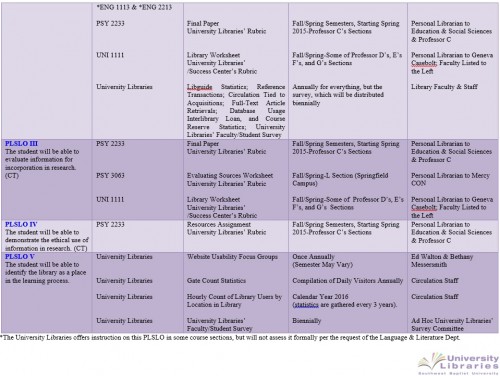

As a result, I developed curriculum and assessment maps that not only contained a list of courses in which specific PLSLOs were advanced, but also began including assessment of data from LibGuides, gate count, interlibrary loan, course reserve, biennial library survey, and website usability testing on the maps as well. All of these statistics can be tied to student-centered learning. Assessment of them enables my library faculty and I to make changes in the way that we market services and resources to constituents.

The maps illustrated in Table 1 and Table 2 below are intentionally simplistic. They provide the library liaisons and faculty in their liaison areas with a visual overview of the information literacy PLSLOs taught and assessed. When the University Libraries moved to the liaison model in 2011, the librarian teaching education majors was not necessarily familiar with the PLSLOs advanced by the library liaison to the Language & Literature Department. Mapping current library involvement in the curriculum created a shared knowledge of PLSLOs among the library faculty. I also asked each librarian to create a lesson plan, which we published on the University Libraries’ website. Since we utilize the letter “x” to denote PLSLOs covered, rather than letters that display the depth of coverage – introduction, reinforcement, mastery, lesson plans provide the librarians and their faculty with a detailed outline of how the PLSLO is developed in the classroom.

Apart from the general visual appeal, these maps also enable us to recognize holes in our information literacy program. For example, there are several departments that are not listed on the curriculum map because we do not currently provide instruction in these classes. Many of the classes that we visit with are freshman and sophomore level. It helps us to identify areas that we need to target moving forward, such as juniors through graduate students.

Table 2 reveals a limited number of courses we hope to assess in the upcoming year. In discussions with library faculty, I quickly discovered that it was more important to start assessing, rather than assess every class we are involved in at present. We can continue to build in formal assessments over time, but for now the important thing is to begin the process of evaluating the learning process, so that we can make modifications to more effectively impact student learning (Oakleaf & Kaske 283).

The University Libraries is a unique entity in comparison to the other academic units represented across campus. This is largely because information literacy is not a core curriculum requirement. As a result, some of the PLSLOs reflected on the assessment map include data collected outside of the traditional classroom that is specific to the services, resources, and educational opportunities that we facilitate. This is best demonstrated by PLSLOs two and five. For example, we know that students outside of our sessions are using the LibGuides and databases, which are integral to PLSLO two – “The student will be able to use sources in research.” For PLSLO five – “The student will be able to identify the library as a place in the learning process” we are not predominantly interested in whether or not students are using our electronic classrooms during an information literacy session. We are interested in students’ awareness and use of the physical and virtual library as a whole, so we are assessing student learning by whether or not students can find what they need on the University Libraries’ website or whether they utilize the University Libraries’ physical space in general.

Transparency in the Assessment Process

Curriculum and assessment maps provide librarians and educators alike with the opportunity to be transparent about the learning that is or is not happening inside and outside of the classroom. I am grateful for the information I have gleaned from the Education Department at SBU along the way because it has inspired a newfound commitment and dedication to the students that we serve.

Although curriculum and assessment mapping is not widespread in the academic library world, some information literacy practitioners have readily embraced this concept. For example, in Brian Matthews and Char Booth’s invited paper, presented at the California Academic & Research Libraries Conference (CARL), Booth discusses her use of the concept mapping software, Mindomo, to help library and departmental faculty visualize current curriculum requirements, as well as opportunities for library involvement in the education process (6). Some sample concept maps that are especially interesting include one geared towards first-year students and another customized to the Environmental Analysis program at Claremont Colleges (Booth & Matthews 8-9). The concept maps then link to rubrics that are specific to the programs highlighted. Booth takes a very visual and interactive approach to curriculum mapping.

In their invited paper, “A More Perfect Union: Campus Collaborations for Curriculum Mapping Information Literacy Outcomes,” Moser et al. discuss the mapping project they undertook at the Oxford College of Emory University. After revising their PLSLOs, the librarians met with departmental faculty to discuss where the library’s PLSLOs were currently introduced and reinforced in the subject areas. All mapping was then done in Weave (Moser et al. 333). While the software Emory University utilizes is a subscription service, Moser et al. provide a template of the curriculum mapping model they employed (337).

So, which of the mapping systems discussed is the best fit for your institution? This is something that you will want to determine based on the academic environment in which you find yourself. For example, does your institution subscribe to mapping software like Emory University or will you need to utilize free software to construct concept maps like Claremont Colleges? Another factor to keep in mind is what model will make the most sense to your librarians and the subject faculty they partner with in the classroom. As long as the maps created are clear to the audiences that they serve, the format they take is irrelevant. In Janet Hale’s book, A Guide to Curriculum Mapping: Planning, Implementing, and Sustaining the Process, she discusses several different kinds of maps for the K-12 setting. While each map outlined contains benefits, she argues that the “Final selection should be based on considering the whole mapping system’s capabilities” (Hale 228).

The curriculum and assessment mapping models I have used for the information literacy competency program at SBU reflect the basic structure laid out by the Assessment Academy Team at my institution. I have customized the maps to reflect the ways the University Libraries facilitates and desires to impact student learning inside and outside of the classroom. In an effort to foster collaboration and create more visibility for the Information Literacy Competency Program, I have created two LibGuides that are publicly available to our faculty, students, and the general public. The first one, which is entitled Information Literacy Competency Program, consists of PLSLOs, our curriculum and assessment maps, outlines of all sessions taught, etc. The Academic Program Review LibGuide provides an overview of the different ways that we are assessing student learning – including website usability testing feedback, annual information literacy reports and biennial student survey reports. Due to confidentiality, all reports are accessible via the University’s intranet.

Acknowledging the Imperfections of Curriculum and Assessment Mapping

Curriculum and assessment mapping is not an exact science. I wish I could bottle it up and distribute a finished product to all of the information literacy librarians out there who grapple with the imprecision of our profession. While it would eliminate our daily struggle, it would also lead to the discontinuation of Eureka moments that we all experience as we grow with and challenge the academic cultures in which we find ourselves.

So, what have I learned as a result of the mapping process? It requires collaboration on the part of library and non-library faculty. When I began curriculum and assessment mapping, I learned pretty quickly that without the involvement of each liaison librarian and the departmental faculty, mapping would be in vain. Map structures must be based on the pre-existing partnerships librarians have, but will identify gaps or areas of growth throughout the curriculum. I would love to report that our curriculum maps encompass the entire curriculum at SBU, but that would be a lie. Initially, I did a content analysis of the curriculum and reviewed syllabi for months in an effort to develop well-rounded maps. I learned all too quickly, however, that mapping requires us to work with what we already have and set goals for the future. So, while the University Libraries’ maps are by no means complete, I have challenged each liaison librarian to identify PLSLOs they can advance in the classroom now, while looking for new ways to impact student learning moving forward.

During the mapping process, I was overwhelmed by the fact that the University Libraries was unable to represent student learning in the same way the other academic departments across campus did. I liked the thought of creating maps identifying the introduction, reinforcement, and mastery of certain skill sets throughout students’ academic tenure with us. However, I quickly realized that this was impractical because it does not take into account the variables that librarians encounter, such as one-shot sessions, uneven representation in each section of a given class, transfer students, and learning scenarios that happen outside of the classroom itself. Using the “x” to define areas where our PLSLOs are currently impacting student learning was much less daunting and far more practical.

It is important to anticipate pushback in the mapping process (Moser et al. 333-334; Sterngold 86-88). When I began attending the Department Chair Workshops in 2013, I quickly discovered that not all of the other departmental faculty were amenable to my presence. One individual asked why I was attending, while another questioned my boss about my expertise in higher education. In the assessment mapping process, faculty in my library liaison area were initially reluctant to collaborate with me on assessing student work. Despite some faculty’s resistance, I was determined to persevere. As a result of the workshops, I established a Community of Practice with faculty in the Education Department and grew more confident in my role as an educator.

I know that there are gaps in the maps, but I have come to terms with the healthy tension that this knowledge creates. While I have a lot more to learn about information literacy, learning theory, curriculum and assessment mapping, etc., I no longer feel under-qualified. As an academic, I continue to glean knowledge from my fellow librarians and the Education Department, looking for opportunities to make modifications as necessary. I have reconciled with the fact that this is a continual process of recognizing gaps in my professional practice and identifying opportunities for change. After all, that is what education is all about, right?

Many thanks to Annie Pho, Ellie Collier, and Carrie Donovan for their tireless editorial advice. I would like to extend a special thank you to my Library Dean, Dr. Ed Walton for believing in my ability to lead information literacy efforts at Southwest Baptist University Libraries back in 2011 when I was fresh out of library school. Last, but certainly not least, my gratitude overflows to the educators at my present institution who helped me to wrap my head around curriculum and assessment mapping. Assessment is no longer a scary thing because I now have a plan!

Works Cited

Booth, Char, and Brian Matthews. “Understanding the Learner Experience: Threshold Concepts & Curriculum Mapping.” California Academic & Research Libraries Conference.

San Diego, CARL: 7 Apr. 2012. Web. 17 Mar. 2015.

“Create a Curriculum Map: Aligning Curriculum with Student Learning Outcomes.” Office of Assessment. Santa Clara University, 2014. Web. 13 Apr. 2015.

“Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.” 2015. Association of College and Research Libraries. 11 Mar. 2015.

Gilchrist, Debra. “A Twenty Year Path: Learning About Assessment; Learning from Assessment.” Communications in Information Literacy 3.2 (2009): 70-79. Web. 4 Mar. 2015.

Gregory, Lua, and Shana Higgins. Introduction. Information Literacy and Social Justice: Radical Professional Praxis. Ed. Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins. Sacramento: Library Juice. 1-11. Library Juice Press. Web. 13 Apr. 2015.

Hale, Janet A. A Guide to Curriculum Mapping: Planning, Implementing, and Sustaining the Process. Thousand Oaks: Corwin, 2008. Print.

Hatfield, Susan. “Assessing Your Program-Level Assessment Plan.” IDEA Paper. 45 (2009): 1-9. IDEA Center. Web. 27 Feb. 2015.

Hayes-Jacobs, Heidi. Getting Results with Curriculum Mapping. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2004. eBook Academic Collection. Web. 26 Feb. 2015.

—. Mapping the Big Picture: Integrating Curriculum & Assessment K-12. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. 1997. Print.

“Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education.” 2000. Association of College & Research Libraries. 11 Mar. 2015.

Levine, Arthur. Generation on a Tightrope: A Portrait of Today’s College Student. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2012. Print.

Manning, Brenda H., and Beverly D. Payne. “A Vygotskian-Based Theory of Teacher Cognition: Toward the Acquisition of Mental Reflection and Self-Regulation.” Teaching and Teacher Education 9.4 (1993): 361-372. Web. 25 May 2012.

Mitchell, John. The Potential for Communities of Practice to Underpin the National Training Framework. Melbourne: Australian National Training Authority. 2002. John Mitchell & Associates. Web. 18 Mar. 2015.

Moser, Mary, Andrea Heisel, Nitya Jacob, and Kitty McNeill. “A More Perfect Union: Campus Collaborations for Curriculum Mapping Information Literacy Outcomes.” Association of College and Research Libraries Conference. Philadelphia, ACRL: Mar.-Apr. 2011. Web. 17 Mar. 2015.

Oakleaf, Megan, and Neal Kaske. “Guiding Questions for Assessing Information Literacy in Higher Education.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 9.2 (2009): 273-286. Web. 21 Dec. 2011.

Perkins, David. Archimedes’ Bathtub: The Art and Logic of Breakthrough Thinking. New York: W.W. Norton, 2000. Print.

Reiss, Rick. “Before and After Students ‘Get It’: Threshold Concepts.” Tomorrow’s Professor Newsletter 22.4 (2014): n. pag. Stanford Center for Teaching and Learning. Web. 7 Mar. 2015.

Sterngold, Arthur H. “Rhetoric Versus Reality: A Faculty Perspective on Information Literacy Instruction.” Defining Relevancy: Managing the New Academic Library. Ed. Janet McNeil Hurlbert. West Port: Libraries Unlimited, 2008. 85-95. Google Book Search. Web. 17 Mar. 2015.

Wiggins, Grant, and Jay McTighe. Understanding by Design. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2005. ebrary. Web. 3 Mar. 2015.

Pingback : Latest Library Links 24th April 2015 | Latest Library Links

Pingback : Hack Your Summer: Part One | hls