Pre-ILS Migration Catalog Cleanup Project

Image by flickr user ashokboghani (CC BY-NC 2.0)

In Brief: This article was written to describe the University of New Mexico’s Health Sciences Library and Informatics Center’s (HSLIC) catalog cleanup process prior to migrating to a new integrated library system (ILS).

Catalogers knew that existing catalog records would need to be cleaned up before the migration, but weren’t sure where to start. Rather than provide a general overall explanation of the project, this article will provide specific examples from HSLIC’s catalog cleanup process and will discuss specific steps to clean up records for a smooth transition to a new system.

Introduction

In February 2014, the Health Sciences Library and Informatics Center (HSLIC) at the University of New Mexico (UNM) made the decision to migrate to OCLC’s WorldShare Management Services (WMS). WMS is an integrated library system that includes acquisitions, cataloging, circulation, analytics, as well as a license manager. The public interface/discovery tool called Discovery is an open system that searches beyond items held by your library and extends to items available worldwide that can be requested via interlibrary loan. We believed that Discovery would meet current user expectations with a one-stop searching experience by offering a place where users could find both electronic resources and print resources rather than having to search two separate systems. In addition to user experience, we liked that both WMS and Discovery are not static systems. OCLC makes enhancements to the system as well as offers streamlined workflows for the staff. These functionalities, along with a lower price point, drew us to WMS. This article will discuss HSLIC’s catalog cleanup process before migrating to OCLC’s WMS.

Before the decision was made, the library formed an ILS Migration Committee consisting of members from technical services, circulation, and information technology (IT) that met weekly. This group interviewed libraries that were already using WMS as well as conducted literature searches and viewed recorded presentations from libraries using the system. This research solidified the decision to migrate.

HSLIC began the migration and implementation process in June 2014 and went live with WMS and WorldCat Discovery in January 2015. Four months elapsed from the time the decision was made to the time the actual migration process began due to internal security reviews and contract negotiation. Catalogers knew that existing catalog records would need to be cleaned up before the migration, but weren’t sure where to start. Because of this, the cleanup process was not started until the OCLC cohort sessions began in June 2014. These cohort sessions, led by an OCLC implementation manager, were designed to assist in the migration process with carefully thought out steps and directions and provided specific training in how to prepare and clean up records for extraction, as well as showed what fields from the records would migrate.

In addition to providing information about the migration, the OCLC cohort sessions also provided information on the specific modules within WMS including Metadata/Cataloging, Acquisitions, Circulation, Interlibrary Loan, Analytics and Reports, License Manager, and Discovery. While the sessions were helpful, the cleanup of catalog records is a time-intensive process that could have been started during the waiting period. Luckily, we were one of the last institutions in the cohort to migrate bibliographic records. This allowed more time to consider OCLC’s suggestions, make decisions, and then clean up records in our previous ILS, Innovative’s Millennium, before sending them to OCLC.

Literature Review

While there is extensive information in the professional literature regarding how to choose an ILS and how to make a decision about whether or not to move to a cloud based system, there is little information about the steps needed to clean up catalog records in order to prepare for the actual migration process. Dula, Jacobson, et al. (2012) recommend thinking “of migration as spring-cleaning: it’s an opportunity to take stock, clear out the old, and prepare for what’s next.” They “used whiteboards to review and discuss issues that required staff action” and “made decisions on how to handle call number and volume entry in WMS;” however, catalog record cleanup pre-migration was not discussed in detail.

Similarly, Dula and Ye (2013) stated that “[a] few key decisions helped to streamline the process.” They “elected not to migrate historical circulation data or acquisitions data” and were well aware that they “could end up spending a lot of time trying to perfect the migration of a large amount of imperfect data” that the library no longer needed. They planned on keeping reports of historical data to avoid this problem. Hartman (2013) mentioned a number of questions and concerns for migrating to WMS including whether or not to migrate historical data or to “start with a clean slate.” They decided that they “preferred the simpler two-tiered format of the OCLC records” to their previous three-tiered hierarchy, but found some challenges including the fact that multi-volume sets did not appear in the system as expected. The cataloger chose to to view this as “an opportunity to clean up the records” and methodically modify records prior to migration. Hartman (2013) also discussed that the “missing” status listed in their previous ILS system did not exist in WMS and that they had to decide how or if they should migrate these records.

While the questions and concerns that these authors mentioned helped us focus on changes to make in the catalog prior to migration, we found no literature that discussed the actual process of cleaning up the records. From the research, it was obvious that a number of decisions would have to be made in the current ILS before the migration would be possible.

Process

In order to make those decisions, the ILS Migration Committee met every other week to discuss what had been learned in the OCLC cohort sessions as well as any questions and concerns. It was important for catalogers to understand why certain cataloging decisions had been made over the years to determine how items should be cataloged in the new system. Our library’s cataloging manual and procedure documentation was read and questions were asked of members on the committee who had historical institutional knowledge. Topics included copy numbers, shelving locations, and local subject headings. Notes and historical purchasing information were closely examined and their importance questioned. Material formats and statuses were also examined before determining what should be changed to meet the new system’s specifications.

Copy Numbers

OCLC recommended taking a close look at copy numbers. A few years ago a major weed of the media and the book collection was conducted. Unfortunately, when items were withdrawn, the copy numbers were not updated in the system. In some cases, copy number 4 and 5 were kept while 1-3 were withdrawn and deleted from the system. In the new system this would appear that the library had 5 copies of a title, while it really owned two. We decided that the actual copy number of an item wasn’t important to our library users because we could rely on the barcode; however, it was important to determine the number of copies so that WMS could accurately identify when multiple copies of an item existed.

In order to make these corrections, a list was run in Millennium for items with copies greater than 1 and then item records were examined to discover how many copies existed in the catalog. Corrections were then made as needed. This was a bigger job than anticipated, but it was a necessary step to avoid post-migration cleanup of the copy numbers in order to prevent errors in WMS.

Shelving Locations

One of the first things we learned in the OCLC cohort sessions was that many of the statuses that we used in Millennium did not exist in WMS. Some examples were:

MISSING

STOLEN

BILLED

CATALOGING

REPAIR

ON SEARCH

Because these statuses were no longer an option, we decided to create shelving locations that would reflect these statuses in WMS. Some of these shelving locations aren’t necessarily physical locations in the library, but rather designations for staff to know where the item can be found. For example, items with a previous status of “repair” in Millennium now have a shelving location of “repair” in WMS. This alerts staff that the item is not available for checkout and is in repair in our processing room. We decided to delete items that had statuses of “stolen” and “missing” prior to migration to better reflect the holdings of our library.

We also decided to delete a number of shelving locations as they were no longer being used or no longer needed. For example, some locations were merged and others were renamed to better reflect and clarify where the physical shelving locations were in the library as well as the type of material the locations held.

Local Bibliographic Data and Subject Headings

WMS uses OCLC’s WorldCat master records for its bibliographic records. This means that WMS libraries all use the same records and must include information that is specific to its library in a separate section called Local Bibliographic Data (LBD). After much discussion, we decided to keep the following fields: 590, 600, 610, 651, 655, 690, and 691. We felt that keeping these fields would create a better record and provide multiple access points for our users.

A number of records for Special Collections had local topical terms in the 690 field and local geographic names in the 691 and 651 fields. For the most part, master records did not exist for these records as they were created locally for HSLIC’s use. When these bibliographic records were sent to OCLC for the migration, the WorldCat master record was automatically created by OCLC as part of the migration process. It was important that these subject headings were migrated as part of the project, so that they were included with the record and not lost as an access point. We also decided that the local genre information in the 655 field was important to retain as it provided an access point on a local collection level. For example, we wanted to make sure that “New Mexico Southwest Collection” was not lost to our researchers who are familiar with that particular collection. Generally, a genre heading contained in the 655 field would be considered part of the WorldCat master record that other libraries could use. Because our local information would not be useful to other libraries, we decided to transfer this information to a 590 local note so that it would only be visible to our library users.

Notes

Decisions regarding local notes that were specific to our institution, such as general notes in the 500 field and textual holdings notes in the 850 field had to be made. We requested that Innovative make the information in the 945 field visible to our catalogers. This is the field that contains all of the local data including item information and is instrumental in the migration process.

500 General Notes

During the migration process, libraries have the option to load local bibliographic data to supplement the OCLC master records. This means that when OCLC receives the library’s bibliographic records, as part of an automatic process the records are compared with OCLC’s master records according to a translation table submitted by the library.

The 500 field was closely examined to ensure that information wasn’t duplicated or deleted. OCLC master records usually contain a 500 note field, a general note that would be relevant to any library that holds the item. For example, some records contain “Includes index” listed in the 500 note field. Because this field already exists within the master record and is relevant for anyone holding the item, we wanted to keep the information in the master record. However, we had a number of notes in this field that were relevant only to our library and we could not simply keep the notes in this field. If we had migrated the 500 field, it would have resulted in two note fields containing the same information in the master record as the note would “supplement” the master record. Because of this, we chose not to migrate information in the 500 field in order to prevent duplicate information. Instead, a list was created in Millennium mainly for Special Collection records that were created locally and not previously loaded into WorldCat. The information in the 500 field was then examined in these special collection records by catalogers to determine whether or not the information was local or general and then manually changed one record at a time. If the information in this field was considered local and only important to HSLIC; it was moved to a 590 field, so that it would be visible to our users in Discovery and staff in WMS, but not to any other libraries who might want to use the record.

Local Holding Records

WMS’s local holding record (LHR) incorporates information from Millennium’s item record with the holding information from the bibliographic record. It includes information like the call number, chronology and enumeration, location, and price. The LHR in WMS was created using the information found in the 945 field and was included in the extracted bibliographic records we sent to OCLC. For the most part, migrating this information was simple except for a few unique cases for our library.

850 Holding Institution Field

The 850 holding institution field is part of the bibliographic record and was labeled in our instance of Millennium as “HSLIC Owns”. This field was used to list coverage ranges or the dates and issues held by our library for journals, special collections material, and continuing resources. This information is usually cataloged in the 863 field within an item or local holdings record; however, HSLIC did not use this in Millennium. WMS reserves the 850 field for OCLC institution symbols with holdings on a particular title, which meant that we could not continue to use the 850 field as we had previously. Because WMS coverage dates are generated from the enumeration listed in the LHR, we explored the possibility of migrating the 850 field from the bibliographic record to the 863 field in the local holding record. Unfortunately, it was not possible to do a global update to cross from bibliographic record to an item record within Millennium during the migration process.

There were two options to create coverage statements in the migration process: 1. Allow the statements to be newly generated in WMS through the holdings statements generating tool or 2. move the current coverage statements to a 590 note. Because there were so many notes that needed to be moved to the 590 field, a decision was made to delete the 850 holding institution fields from almost all of our records and use the automated summaries generated in WMS. This left all serial records without coverage dates during the migration project in Millennium; however, we believed it would make the migration process to WMS easier.

Special Collection records did not include item-level date and enumeration in the item records and were instead cataloged at a box or series level. This eliminated the possibility of using WMS automated summaries. Because of this, coverage statements were moved to a 590 public note for all special collections records. This way the information was retained in the system, while still creating an opportunity to change the formatting at a later date if needed.

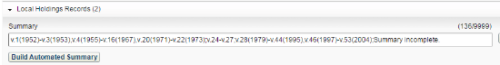

After the migration, it was discovered that the system generated coverage dates were not as complete or as easy to read in WMS as they had been in Millennium. It is an ongoing project to clean up and keep these summaries current in the new system. Below is a screenshot of how the coverage dates appeared on the staff side of Millennium:

![]()

This is how the coverage dates appear in WMS:

In hindsight, we should have migrated the 850 field to a 590 field to keep the information as local bibliographic data in addition to using the WMS automated summary statement. The coverage dates would then have appeared in a public note, which would have given our staff and users an additional place to look for the coverage dates. It would also have given technical services staff a point of comparison when cleaning up the records post-migration.

Info/Historical Records

In Millennium, a local practice was developed to keep notes about subscriptions as an item record under the bibliographic record. In WMS, these could not be migrated as items because they were not real items that could be checked out, but rather purchasing notes that were only important to staff. Because of this, it was important that these notes not be visible to the public. These notes were a constant topic of discussion among the implementation team members and with the OCLC cohort leaders.

One idea was to migrate them from an item to a bibliographic field by attaching the note as an 850 holdings institution field. Unfortunately, just as it was not possible to do a global update to cross from bibliographic record to item record, it was also not possible to to cross from item record to bibliographic record. OCLC tried to help with this, but could not find a solution for crossing between record types. Even if this were possible, the above mentioned issues with the 850 field would have been encountered and the information would have to be moved to a 590 field to retain it.

Because this seemed complicated, a list was created of all of the info/historical records in Millennium and then exported to Excel to create a backup file containing these notes. Soon after this was completed, OCLC developers found a way to translate the information from the 850 field to the 852 non-public subfield x note in WMS as part of the migration. Historical purchasing information is now in a note that is only visible to staff in WMS.

Continuing Resources

We have found continuing resources to be challenging in WMS. Previously, we had used OCLC’s Connexion to create and manage bibliographic records and used material types that the system supplied. While “continuing resource” is a material type in Connexion, it is not a material type in WMS. Because of this, an available material type in the new system was chosen and then records were changed in Millennium to match the new system. To do this, another list was created in Millennium of items with “continuation” listed as the material type. The list was then examined and a determination was made as to whether or not the materials were actually still purchased as a continuation. Most of the titles were no longer purchased in this way, so the migration presented an opportunity to make these corrections in the system.

Not every item listed as a “continuation” in Millennium was a serial item. In some cases the titles were part of a monographic series. Decisions then had to be made whether to use a serial record or a monograph record for items that had previously been considered continuing resources. For items that had only an ISBN, we chose the monograph record and for those with an ISSN, we chose the serial record; however, many items had both an ISBN and an ISSN. The decision was more difficult in these instances and continues to be difficult for these items because the format chosen affects how patrons can find the item in Discovery. This is addressed in more detail below.

Analytic Records

At the beginning of the migration process, OCLC inquired about specific fields and data elements in our records to identify potential errors in the migration process which could be addressed before migrating. One question was whether the data contained linked records. At first, we had no idea what this even meant, so we answered “no” on our initial migration questionnaire. A few short weeks before the scheduled migration date, the linked records were discovered in the form of series analytic records. A series analytic record is basically a record that is cataloged as an overarching monographic series title that is then linked to individual titles within that series. This means that the item record is linked to the overarching bibliographic record for the series as well as the bibliographic record for the individual title, which then links both bibliographic records. Unknown to those working on the migration project, previous catalogers had an ongoing project to unlink all of these analytic records when a monographic series subscription was no longer active. Notes were found on how to unlink the records, but no notes on what the titles were or where the previous catalogers left off in the project were found. Unfortunately, we had no way to identify linked records in Millennium.

We unlinked as many of the records as possible before the migration, but finally had to send the data to OCLC knowing that many linked records still remained. These records migrated as two separate instances of the same barcode, which created two LHRs in WMS, subsequently causing duplicate barcodes in WMS. After the migration, OCLC provided a number of reports including a duplicate barcode report, so that these duplicate instances could be found. To correct these records, the item was pulled and examined to determine if the serial or the monograph record best represented it. The local holdings record was corrected for the title and the LHR from the unchosen bibliographic record was deleted.

In Millennium, the choice between representing an item with a serial or monograph record had few implications for users. However, in WMS, choosing a serial record could allow for article level holdings to be returned in Discovery, while choosing a monograph record would not. Conversely, choosing a serial record for an item which looks like a monograph might make the item more difficult to find if users narrow their search to “book.” Because of this, careful review of items and material types was necessary to help create the best user experience.

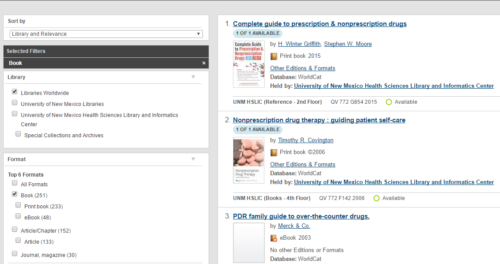

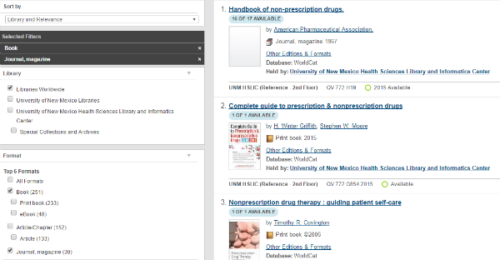

For example, “The Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs” looks like a book with a hard cover to most library users and even staff. In Discovery, if the format is limited to “journal,” the title is the first search result:

If the search is limited to the format “book,” the title is not found on the first page of the search results.

Serials

As was mentioned previously, OCLC relies on the 945 field to view all item information. For the most part, serials records contained the 850 HSLIC Owns field that was discussed earlier. The 945 subfield a was used to list the following distinctions: Current Print Subscription, Current Print and Electronic Subscription, and Electronic Subscription. Because the 945 subfield a also contained the volume dates, we chose to move this information to a 590 local note field.

Once those notes were moved, we found that enumeration and chronology was entered in various subfields within the 945 field. The date was usually in subfield a, volume notes were found in subfield d, while the volume number was in subfield e. The below example is taken from an extraction in Millennium and shows the enumeration and chronology for volume 53 of the journal “Diabetes” published in 2004. The first line shows an example of a note that this volume is a supplement, while the second line shows a more typical entry with volume number and coverage.

945 |c|e53|a2004|dSupplements|

945 |c|e53|a2004:July-2004:Dec|

The enumeration and chronology was constructed from these subfields where possible; however, if this information was repeated in a different subfield, it had to be cleaned up post-migration.

Electronic Resources

We decided not to migrate electronic resources cataloged in Millennium to WMS. Electronic resources are managed within Collection Manager, which is WMS’ electronic resource manager. It was specified in the translation table that any record with a location of electronic resource not be migrated to the new system. Unfortunately, many of the electronic resources records unintentionally migrated. They may have been attached to a print record or perhaps did not have the location set as electronic resource. Holdings had to be removed from these records post-migration.

Before migration, we decided to delete records for freely available e-books from Millennium. Most of these resources were provided for the public via government websites hosted by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and could easily be accessed through other means of searching. These resources could be added to Collection Manager post-migration if deemed important.

Similarly, electronic records were not migrated directly from Serial Solutions, our previous electronic resource manager. Instead, electronic resources were manually added to Collection Manager for a cleaner migration. All electronic resources are shared with University Libraries (UL), the main campus library, so close collaboration with UL was necessary in order to share and track these resources. While all HSLIC resources were shared with UL and all UL resources shared with us, we decided to select only the resources that were relevant to the health sciences in Collection Manager. This created a more health sciences focused electronic resources collection, so that titles relevant to these subjects are displayed at the top of the search.

Suppressed Records

One of OCLC’s slogans is “because what is known must be shared,” so it makes sense that WMS does not have the capability to suppress records. If an item has our holdings on it and has an LHR, then it is viewable to the public in Discovery. For the most part this concept worked for us. There were two record types in Millennium where this idea presented challenges: suppressed items and equipment records.

Suppressed Items

At the time of migration, there were around 1200 books that had been removed from the general collection and stored in offsite storage for future consideration for adding to Special Collections. These records were suppressed in Millennium, so that only staff could see them in the backend. Adding these items back into the collection was considered, so that records would not be lost, but it was finally decided this would be far too time consuming in the middle of the migration and that many of the titles would probably be deleted later on.

Instead, another list was created in Millennium containing items in offsite storage with a status of “suppressed”. An Excel spreadsheet was then created that contained the titles, OCLC numbers, and even the call numbers of all of the formerly suppressed titles, allowing for easy reference to the items in storage. We instructed OCLC not to migrate any records with a status of suppressed.

Equipment Records

Similarly, there were a number of equipment records that were only viewable and useful to staff at the circulation desk. These records were for laptops, iPads, a variety of cables and adaptors, even some highlighters, and keys. These items all had barcodes and could be checked out, but patrons had to know that they existed in order to ask for them. While this never seemed to be a problem for users and it did seem strange to create bibliographic records for equipment items, it was decided to create brief records and then migrate them anyway in hope of promoting use.

Now users have the ability to see if a laptop is available for checkout before even asking. While the idea of these records is a bit unorthodox from traditional cataloging, creating the records ultimately added to the service the library was already providing in addition to providing a way to circulate the equipment using WMS.

Conclusion

Although there were a number of steps, a number of surprises, and a number of decisions that had to be made, the pre-migration cleanup process was definitely worth the work. Many errors were discovered post-migration, but without doing the initial clean up, there would have been even more problems.

At HSLIC, we have one full time cataloger/ILS manager and one full time electronic resources/serials librarian. It took nearly 6 months to clean up catalog records before migrating to WMS. Starting the cleanup process earlier would have saved us a lot of work and resulted in cleaner records to migrate.

We should have started looking for the linked series analytic records immediately. This would have given us more time to identify the records, unlink them, and decide which record best represented the item before sending the records to OCLC. This would have prevented post-migration cleanup of duplicate barcodes and prevented circulation staff any confusion when trying to check these items out to users.

Five out of eight members of HSLIC’s ILS migration committee had worked at HSLIC less than a year before we began the migration process. This provided a balance between historical institutional knowledge with new perspectives. It helped us look at the catalog with fresh eyes and allowed us to ask “why” whenever the answer was,“that is the way we have always done things.” If “why” couldn’t be answered or no longer seemed relevant, we considered making a change.

The catalog should reflect what is on the shelf and what is accessible electronically. The online catalog is the window to the library itself and should accurately represent what the library holds. Because of electronic access to ebooks and ejournals, some of our users won’t ever step into the physical library, which makes the accuracy of the online catalog or discovery layer even more important. Even if your library isn’t moving to a new ILS, it is important for catalogers and technical services staff to ask, “What is in the library’s catalog?” and then ask “Why?” As we discovered at HSLIC, keeping notes and shelving locations just because “that is what had always been done” in some cases was no longer compatible with the new system and in other cases was no longer efficient or comprehensible. Sometimes change is exactly what is needed to keep the catalog relevant to library users.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the peer reviewers, Violet Fox and Annie Pho, for helping me focus and clarify my ideas and experiences in this article. You both made the peer review process an interesting and enjoyable experience. Thank you to Sofia Leung, publishing editor, for guiding me through the process. I would also like to thank all of the members on the HSLIC ILS Migration Committee who made the migration possible. I would especially like to thank Victoria Rodrigues for her hard work on cleaning up the serial records and adding our electronic resources to the new system.

Works Cited

Dula, M., Jacobsen, L., Ferguson, T., and Ross, R. (2012). Implementing a new cloud computing library management service. Computers in Libraries, 32(1), 6-40.

Dula, M., and Ye, G. (2013). Case study: Pepperdine University Libraries’ Migration to OCLC’s Worldshare. Journal of Web Librarianship, 6(2),125–132. doi: 10.1080/19322909.2012.677296

Hartman, R. (2013). Life in the cloud: A WorldShare Management Services case study. Journal of Web Librarianship, 6(3),176-185. doi: 10.1080/19322909.2012.702612

OCLC. (2015) Accessed January 14, 2016, from https://www.oclc.org/en-US/share/home.html