Sparking Curiosity – Librarians’ Role in Encouraging Exploration

In Brief

Students often struggle to approach research in an open-minded, exploratory way and instead rely on safe topics and strategies. Traditional research assignments often emphasize and reward information-seeking behaviors that are highly prescribed and grounded in disciplinary practices new college students don’t yet have the skills to navigate. Librarians understand that the barriers to research are multidimensional and usually involve affective, cognitive, and technical concerns. In this article we discuss how a deeper understanding of curiosity can inspire instructional strategies and classroom-based activities that provide learners with a new view of the research process. We share strategies we have implemented at Oregon State University, and we propose that working with teaching faculty and instructors to advocate for different approaches to helping students solve information problems is a crucial role for librarians to embrace.

By Hannah Gascho Rempel and Anne-Marie Deitering

Introduction

Every librarian who has helped a student develop an academic argument knows about those topics. Every first-year composition or speech teacher knows them too. Some instructors ban them outright; others are more subtle in their disapproval. While some instructors who ban topics because they are particularly polarizing or controversial, many of our colleagues who teach writing tell us they were driven to create a ban list for a different reason. They ban topics that are overdone, and that they don’t want to see again. When they see topics like “body image and the media” or “concussions in the NFL,” based on their past experiences with papers on these topics, they have learned that the final paper will rarely be provocative, innovative, or even interesting.

If instructors don’t use ban lists, they see these same topics dozens of times a term. So why do students continue to gravitate to these topics? And what can we as librarians do about it? It is easy to look at the fifteenth marijuana legalization paper and think that students aren’t trying, aren’t engaged, or just don’t care about the course. And in some cases, those things may be true. Students have a lot going on and sometimes a research assignment won’t be at the top of their list of priorities. But in this essay, we are going to examine this question from another perspective and discuss ways that providing space for curious exploration can reframe the research paper assignment.

Librarians and the Exploratory Research Process

The importance of open-minded exploration in the research process is evident from a basic review of seminal research on information literacy. Carol Kuhlthau’s highly-cited model of information seeking describes an exploratory, learning-focused research process. ((Kulthau’s 1991 article in JASIST, “Inside the Search Process: Information Seeking from the User’s Perspective” has been cited 609 times in Web of Science, most recently this month, and almost 2,300 times in Google Scholar.)) At Oregon State (OSU), we enjoy a well-established, creative and productive partnership with rhetoric and composition faculty. This partnership dates back almost twenty years and has focused on working with students in a first-year composition course. Our partnership and the curricular choices for this course were deeply informed by Kuhlthau’s interpretation of the academic research process. Over the years, this course has evolved, but our goals remain consistent: to introduce students to an exploratory, open-minded, inquiry-driven research process. ((To trace this history of this collaboration, see McMillen, Miyagishima and Maughan 2002; and Deitering and Jameson 2008.))

As librarians, we bring this focus on research as a complex learning process to our work with faculty, and we consider that process in all of its dimensions: affective, cognitive, and technical. Here again, Kuhlthau is influential in shaping our thinking. She highlights the fact that information-seeking is an inherently uncertain process, and she considers the emotional impact that this uncertainty can create for the learner (Kuhlthau 1993). To understand how and why our students do what they do with research assignments, we need to consider the range of influences on their behaviors.

Our current thinking about students’ information seeking behaviors went in a new direction based on an assessment project we conducted in OSU’s first-year composition courses. In 2013, we started reviewing a stack of ninety student essays to answer a fairly typical, yes or no question: can first-year composition students accurately identify their sources in order to apply the appropriate citation style? Answering that question became much less important to us, as almost immediately, we found that the papers we were reviewing pointed to a much more complicated question: how does the topic a student selects affect their willingness or ability to engage in an exploratory research process? Or, to approach this question from a different direction: Can we teach an exploratory research process if we start after our students have already selected their topics?

The first-year composition curriculum at that time featured three major writing assignments used in all sections. The second of these, a metacognitive narrative in which the students explicitly described their research process and the sources found, was the paper used for the assessment project. We already knew from our conversations with the graduate teaching assistants and faculty who taught first-year composition that this metacognitive assignment was difficult to teach, difficult to assess, and difficult for students to grasp. What we did not know, until we read these papers, was how boring and lifeless most of the papers were.

We want to pause here to emphasize that we are not criticizing the effort, attention, or ability that students brought to these papers. Papers that were carefully crafted and well thought-out were just as dull as those that were incomplete, rushed, or messy. The composition instructors confirmed to us these metacognitive papers were uniquely (and almost universally) difficult to read. We knew that many students had never been asked to produce a paper that included this level of self-reflection about the research process before, and that assignment design certainly accounted for some of the problems we observed. However, we did not think that the assignment itself explained all the issues we observed. We struggled with the question of why these papers were so lifeless, until Hannah had an epiphany: While every one of these papers described a research process, almost none of students described learning anything new from their research. The processes described were almost completely devoid of curiosity.

Even though students were told to construct a narrative that described their thinking throughout the entire research process, the majority of papers started with a description of their first search in library databases. Most students skipped topic selection entirely. A few started with a vague sentiment: “ever since I was a child I have loved the oceans.” And a few were brutally honest: “I chose this topic because I wrote my senior project on it last year.” The entire sample was dominated by overused topics familiar to any librarian or composition instructor: body image and the media; videogames and violence; marijuana legalization; or lowering the legal drinking age.

Research from Project Information Literacy (http://www.projectinfolit.org/) helps us understand why students gravitate toward familiar, overused topics rather than exploring new topics. These old standbys make students feel safe as they navigate the inherent uncertainty of the research process. In their 2010 paper, Alison Head and Michael Eisenberg show that most students (85%) identify “getting started” as their biggest challenge in research writing. In their qualitative analysis Head and Eisenberg identify a metaphor that sheds some light on how students feel about topic selection: gambling. To students, committing to a research topic is like rolling the dice. When students choose an unfamiliar topic, they don’t know what they will find and they do not know if they can ultimately meet their instructor’s expectations. Even worse, they must invest weeks and weeks of work into a project that may or may not pay out in the form of a good grade (Head and Eisenberg 2010).

In this context, it is not surprising that students prefer topics they have used before, or that they know many other students have successfully used before. These topics represent safe choices. They know these topics will “work,” because they have worked in the past. Students may not know exactly what they are being asked to do in their first “college-level research paper,” but with these topics, they know they are giving themselves a reasonable chance at success.

However, the same qualities that make these topics feel safe for students make them problematic for instructors and librarians. We want students to start thinking about research as a learning process and as an opportunity to explore new things. We know that all students will not have this experience with every research assignment they complete. Students have to juggle many competing demands on their time, and they will not connect with every assignment they have. As a result, instructors and librarians must create conditions where students feel motivated, capable, and safe enough to explore and learn in the research process. Because of our reflections on the student paper assessment project, we realized that as instruction librarians we needed to enter the process earlier, at the topic selection stage, and that we needed to think more intentionally about how to create an environment that encourages curiosity.

Curiosity and Exploration

Curiosity has been defined as “the drive-state for information” (Kidd and Hayden 2015: 450). In this sense, curiosity is a part of any academic research process, since all students will, at some point, need to find information they do not have. For example, finding a quotation to support a claim one has already made would require curiosity. In the context of our work as librarians with the first-year composition course, however, curiosity meant more than this. We were trying to introduce research as an opportunity to learn new things, to explore new perspectives, and to synthesize new ideas into an original argument. If students clung to topics they already knew a lot about, it seem unlikely that they could experience the research process in this new way. However, to test this assumption we needed to find out more about our students and more about curiosity.

To learn more about our students, we designed a small qualitative study that allowed us to track five students’ experiences through the first-year composition course. We gave students a curiosity self-assessment test (discussed in more depth later in this article), interviewed each student twice during the term, and also analyzed each student’s graded work. In the interviews we asked students both implicitly and explicitly how curiosity impacted their behaviors. This project confirmed what we had learned in our assessment of previous student research papers and through reading the literature on students’ information seeking behaviors: when it comes to research assignments, even curious students will avoid topics they do not know anything about, and they will do so to avoid risking failure.

Curiosity and Cognition

To learn about curiosity, we turned to the research literature. A small body of work by cognitive psychologists attempting to define—and develop instruments to identify—different types of curiosity gave us a framework for understanding what sparks curiosity in the first place (Collins et al. 2004; Litman and Jimerson 2004; Loewenstein 1994; Zuckerman and Link 1968). However, these researchers are interested in identifying those aspects of curiosity that are context dependent and those that are inherent personality traits. Our focus as instruction librarians was different; we wanted to know if there are aspects of curiosity that can enhance how we design and teach research assignments. The cognitive psychologists identified several different types of curiosity, and we selected three types we believe have particular value in the composition classroom based on our direct experiences with students: epistemic, perceptual, and interpersonal curiosity.

Epistemic curiosity is the drive for knowledge and the desire to seek information to enjoy the feeling of knowing things (Litman et al. 2005). Epistemic curiosity pushes people to figure out how things work; and it can be concrete (e.g., sparked by a desire to solve a puzzle, or take apart a machine) or abstract (e.g., sparked by a desire to understand theory or abstract concepts). Before starting our own exploration of curiosity, we would have probably defined “curiosity” in the classroom setting solely as epistemic. We assumed that curiosity sparks people to ask questions when they encounter new information—in the classroom and in the world—and that students who are both curious and engaged can always find an interesting research topic in those questions. However, we were not seeing that behavior play out in many of our students’ research papers, and instructors confirmed that many students who were engaged and interested in learning were not always driven by this type of curiosity.

Perceptual curiosity is sparked by the drive to experience the world through the senses—to actually touch, hear, and smell things (Collins et al. 2004). The desire to try new flavors or to touch interesting textures may be easy to relate to, but this kind of sensory experience rarely comes up in the traditional classroom. Traditional research assignments require students to transfer their learning out of the classroom, but the classroom experience remains focused on the facts, figures, ideas, and theories found in texts and does not extend to embodied or physical experiences. This disconnect is unfortunate because the first encounter with something new is usually through the senses. Perceptual curiosity, as a concept, immediately pushed us to think more expansively about how curiosity could connect to an academic research process. Learning activities that ask students to engage their senses while in the lab or outside on a field trip could help spark students to seek different types of information to make sense of what they were hearing, smelling, or touching.

Curiosity sparked by the desire to know more about other people is interpersonal curiosity (Litman and Pezzo 2007). Interpersonal curiosity has an element of snooping or spying in some situations. But this curiosity type also includes behaviors driven by empathy, or an interest in other people’s emotional states, and can be used to reduce uncertainty about how others are feeling or what they are doing. There are classroom assignments where students learn to conduct interviews or observations that can connect to this type of curiosity. Similarly, learning activities that connect students to human experience—like guest speakers, interviews, documentaries, panel discussions, or TED talks—may be inspiring for students who are motivated to understand how other people connect to their topic at an emotional level.

Conceptualizing the cognitive aspects of curiosity in a more multi-faceted way prompted us to think about additional factors related to curiosity, and how we might tie these different approaches to being curious to the research process.

Curiosity and Affect

In an effort to generate interest in the research process, many instructors tell students to choose a topic they are “passionate” about, which can make the prospect of engaging for the first time with academic writing even more stressful. Many of students hear “passion” and think of controversial topics where their minds are very firmly made up. On a cognitive level, it can be challenging for students to learn new things about these topics. But on an affective level, students who already see research projects as a time-intensive “gamble” can feel that this well-meaning directive has raised the stakes even higher. Now they have to come up with a convincing argument—convincing to an audience they don’t really know much about—that expresses a point of view about which they feel deeply.

The research on curiosity further emphasizes the importance of the affective domain (Litman and Silvia 2006). When learners are anxious, worried, or concerned that they cannot complete a task, they are less likely to make room for curiosity. The uncertainty inherent in choosing an unfamiliar topic can be too much to bear. In the context of a traditional research assignment, a student’s choice to play it safe, and avoid the gamble of an unfamiliar topic, is eminently sensible. Years of experience with school have taught students that they will not be evaluated on their willingness to take risks, but on their ability to meet predetermined expectations. The risks inherent in taking a curiosity-driven approach to research may seem too great to overcome.

Opportunities for Applying Curiosity: Experiences from OSU

To overcome these barriers, students must be convinced that the risks are worth it—and librarians cannot affect this change by themselves, particularly within the confines of a one-hour library instruction session. No matter how engaging or compelling librarians are, in our role as guest lecturers, we cannot expect to convince students to take risks that might threaten their ability to meet their (grading) instructors’ expectations. No matter how empathetic and approachable librarians are, we cannot expect students to trust relative strangers to help them navigate the anxiety and uncertainty that is inherent in a curiosity-driven research process. To build an environment for curiosity in the first-year composition classroom, librarians have to work collaboratively with the faculty designing the curriculum, the GTAs teaching the sections, and the students doing the work.

At OSU, we have worked with our partners in the first-year composition program to try out a variety of approaches for creating spaces for curiosity in the classroom. Some of these approaches include changing the language used to discuss the research process, recognizing the role affect plays on students’ research behaviors, building in multiple opportunities and rewards for broad exploration of ideas and sources, and providing prompts for students to reflect on how curiosity influences the way they think about research. These activities are discussed in more depth below so that other librarians might consider adopting the approaches that work well in their context.

Adopting the Language of Curiosity and Exploration

At OSU, we built on our longstanding partnership with first-year composition faculty to incorporate curiosity into faculty development and GTA trainings. A key focus of these trainings is on the importance of language. Wendy Holliday and Jim Rogers (2013) demonstrated that the language we use to discuss the research process matters. Using discourse analysis in the first-year composition classroom, they found that students are more likely to engage in an exploratory research process when their instructors emphasize “learning about” a topic instead of “finding sources.” Building on this research, we suggest that first-year composition instructors should also encourage students to choose topics they are “curious” about instead of “passionate” about.

In addition, every year we share our findings about curiosity and learning with the first-year composition GTAs in a required training session that takes place before fall term. We discuss the importance of the affective domain in research instruction and give new GTAs a chance to experience research from their students’ perspectives. Throughout the term, we help instructors actively reflect on the affective and cognitive challenges students face, and we provide repeated opportunities to practice using terms like “curiosity,” “exploration,” and “learning” to describe the research process.

Encouraging Early Exploration of Different Sources

We also developed a variety of activities librarians could use to engage students with curiosity in the one-hour library instruction environment. To create opportunities for students to engage with their own curiosity, and to practice relying on their curiosity strengths in research, we used our library sessions to encourage browsing for a wider range of topics. But we also encouraged students to browse outside the journal literature, using sources that would help them place scholarly sources in a meaningful context.

Our students, like many first-year composition students, were required to use several source types in their final essays, including peer-reviewed journal articles. And our students, like many first-year composition students, frequently struggled with this requirement. Research articles, written for experts, were an unfamiliar genre and most of our students did not have the skills or experience to break them down and identify the pieces most likely to be useful in a first-year composition paper. The vocabulary and concepts were often dense and could not be easily digested in one or two (or five or six) readings. Even when an individual article was intellectually accessible, most first-year composition students did not know enough about the surrounding discourse to contextualize or evaluate the article as an expert would.

If these were the only barriers we had to navigate—if all first-year composition students selected topics well-represented in the scholarly literature—we could develop strategies to deal with each one. We found that there was another, more deeply entrenched, barrier that was harder to overcome: because most of our first-year composition students did not know what they could expect to find in the scholarly literature, they could not devise queries or research questions that could be usefully explored in that literature. As a result, students sometimes chose topics that were not discussed in peer-reviewed journals. No matter how well we taught students to find, read, use, and cite scholarly articles, if their argument was about the lack of parking on the OSU campus, they were going to find the scholarly article requirement frustrating and impossible to navigate. Sometimes, their topic choice meant they could not see the value in the sources they did find. If they were looking for the kind of general overview they were used to in encyclopedias and textbooks, students were unimpressed with the narrow, focused information reported in peer-reviewed articles.

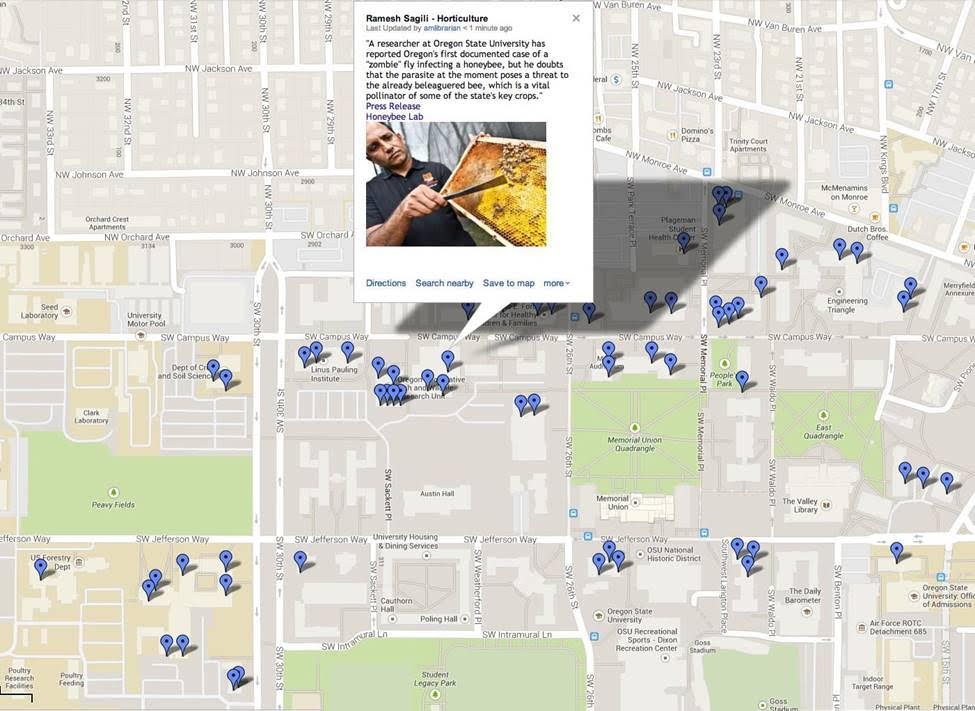

To encourage students to follow their curiosity and set them up for success in their searches, we developed different ways for students to browse the scholarly literature before choosing paper topics. We developed activities that required students to browse press releases using the OSU research channel (http://oregonstate.edu/ua/ncs/) or aggregators like Science Daily (http://sciencedaily.com) or EurekAlerts (https://www.eurekalert.org/). To create a visual framework students could use to contextualize that research, we developed a Google Map of our campus that combined information about researchers with snippets from press releases about their new discoveries (see Figure 1).

Google Map of OSU with researcher information points by Rempel and Deitering

We required students to identify a topic that sparked their curiosity in these sources, knowing they could build on that initial spark to explore effectively in the scholarly literature. In addition, the press release or news story usually provided some context to help students understand the significance of a study because these sources were written for general audiences. Analyzing a press release or news article about a research study helped students understand what they could expect to find in different source types more organically than arbitrary requirements did, and it also helped them to understand the different types of original research scholars do. After students learned about a study in these general sources, we explored alternate ways to search the library’s web-scale discovery tool by teaching them to search for the researcher, not the study. Learning more about the author(s)’ background provided another layer of context that the students could use to make sense of their article.

As we revised and refined these activities, and observed students completing them, we identified some best practices for encouraging curiosity-driven research in the library instruction one-shot environment:

- Encourage students to choose topics they know little or nothing about by creating or finding relevant browsing environments for them to explore.

- Frame the goals for the session around curiosity and exploration instead of finding sources.

- Create circumstances where students can be successful navigating assignment requirements by narrowing the scope of those browsing environments to focus on topics discussed in the scholarly journals they are required to use.

- Expose students to resources that help them put their sources in context.

- And, most importantly, keep the stakes of the in-class activities low.

We did not hide the fact that some students might find a research paper topic through these activities, but we made it clear that they would not be required to write their paper on the topic they used in the session. Choosing a focus for their activities in the library session was a commitment of an hour, not a term. When students saw for themselves that a topic was viable, however, these temporary topics sometimes became more attractive. We also lowered the stakes for individual students by having them work in pairs or small groups to analyze unfamiliar sources and materials whenever possible.

Encouraging Self Reflection on Curiosity

Opportunities to play with curiosity in the classroom are important, but it soon became clear that if we wanted students to transfer what they learned in the first-year composition classroom to other situations, they needed additional opportunities for reflection and metacognition. They needed to analyze and understand their own curiosity, think about its role in the academic research process, and figure out how curiosity might shape their thinking and learning more generally, beyond the first-year composition classroom. Without metacognition, it is difficult to transfer learning from one domain to another, because for many students, this act of self-reflection does not come naturally (Bowler 2010).

One activity we developed to make the mental framework of curiosity types visible is a Curiosity Self-Assessment. Most of the work cognitive psychologists have done with the curiosity types is descriptive; we saw an opportunity to use the instruments developed by these researchers to help students reflect on their own curiosity preferences. We were guided by an important assumption as we worked with these instruments: that all humans are curious, at least at some level (Kidd and Hayden 2015). As a result, the Curiosity Self-Assessment we constructed does not ask “Are you curious?” and it does not promise to answer the question, “How curious am I?” Instead, it asks, “How are you curious?” That guiding question works well for us in the research assignment context. Even if some students feel sparks of curiosity less strongly than others, they all have research assignments to navigate. And they can all benefit from understanding different ways that other people can feel curious about some ideas or concepts.

We created the Curiosity Self-Assessment survey by integrating ten questions each from three different curiosity instruments: epistemic, perceptual, and interpersonal. The Curiosity Self-Assessment has 30 Likert-style questions and takes about 15 minutes to complete. See Table 1 to get a sense of the types of questions that make up the self-assessment. Find the full 30-question Self-Assessment here: http://info-fetishist.org/2014/02/06/onw2014/.

| Almost Never | Sometimes | Often | Almost Always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epistemic Curiosity | ||||

| When I learn something new, I like to find out more | ||||

| I find it fascinating to learn new information. | ||||

| I enjoy exploring new ideas. | ||||

| Perceptual Curiosity | ||||

| I enjoy trying different foods. | ||||

| When I see new fabric, I want to touch and feel it. | ||||

| I like to discover new places to go. | ||||

| Interpersonal Curiosity | ||||

| I wonder what other people’s interests are. | ||||

| I like going into houses to see how people live. | ||||

| I figure out what others are feeling by looking at them. | ||||

This instrument has been a useful tool to introduce conversations about curiosity with both students and faculty, and we will discuss those applications in the rest of this section. First, however, we need to talk about its limits. We specifically developed the tool to use as a self-assessment exercise that would then be paired with classroom activities guiding individuals to reflect on the different ways in which they are curious. The Likert scale used in the survey doesn’t reflect any inherent or objective value and as a result should not be used to give a curiosity “grade.” For more on the specifics of scoring this Self-Assessment, see this blog post: http://info-fetishist.org/2014/02/07/onw2014b/.

The Curiosity Self-Assessment can be used in the classroom environment to get students thinking about the role of curiosity in the research process and about the wide range of topics they might explore. While it is important to explain the nature and purpose of the assessment, this can be done quickly before assigning it as homework. In our experience, students find that the types are logical and easy to understand with just a little background explanation. In addition, it is unlikely that anyone will be upset or confused by what they find. Discovering that you are “perceptually curious” (or “interpersonal” or “epistemic”) doesn’t feel as loaded as labels like “introvert” or “extrovert” might. And as is the case with all self-assessments, the process of taking this survey is itself an opportunity for learners to start thinking differently about curiosity. Metacognitively reflecting on their learning behaviors promotes the ability to develop new behaviors and adapt what they have learned to new contexts.

Challenges and Limitations

In the years since we started working to embed curiosity in the first-year composition course, the curriculum for that course has undergone a significant change. Instead of writing a traditional argument paper, with required source types all students must use, students now complete a scaffolded, multi-stage rhetorical analysis using sources appropriate for their specific rhetorical situation (see this video for an overview of the current approach: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bWXRTtwS-f4). This shift has provided many opportunities to embed curiosity throughout the research process. Students start by choosing a rhetorical artifact to analyze instead of “choosing a topic,” which provides an opportunity to build in activities that incorporate all of the curiosity types. Additionally, the new rhetorical analysis paper is unfamiliar to many students, which makes it more difficult for them to use familiar topics, sources, and habits as they write it.

However, there are significant challenges that will likely persist as long as we try to embed curiosity and exploration in the classroom context. The first of these comes from the fact that most students are not driven by an intrinsic or personal desire to learn simply because they have been assigned a research project. We are hoping to activate their curiosity and therefore spark that desire to learn, but we must recognize that when a student has a required paper to write, the initial motivation to go out and do research will almost always be external, imposed upon them by the first-year composition instructor. Many students keep this external focus throughout and are motivated more by their desire to do well in class and to meet their teacher’s expectations than by an intrinsic need to learn the content (Senko and Miles 2008). To encourage curiosity in this context, we need to work even more closely with the faculty and GTAs who teach first-year composition to develop ways to reward students for taking intellectual risks and engaging in exploratory research.

The need for more structured, positive feedback to encourage exploratory behaviors relates to the second challenge: a curiosity-driven, exploratory research process cannot be taught as a standalone part of the first-year composition curriculum. Students need to see curiosity modeled for them over and over. They need to hear the research process described in terms of learning and exploration at every stage. To make this change, we must give the people who are in the classroom every day the tools, vocabulary, and conceptual understanding they need to do this work. At OSU, we now devote more (and more) of our time to teaching the teachers. At this point, we do not teach one-shot library sessions in first-year composition, but are instead embedded in the required seminar that all new first-year composition instructors must take.

Conclusion

As librarians, we are usually asked to work with students to help them find sources. However, we also know that this part of the research process is not where many of our students struggle the most. Think back to your own experience as a student. Was there a research paper or project that was particularly meaningful? Can you remember what you learned writing that paper? Chances are good that at some point in that research process you were curious, you learned something new, and you created new meaning or new knowledge for yourself. Instructors and librarians want students to have this type of experience, but it can be very challenging in a required course like first-year composition, and may be impossible when students have already committed to going through the motions with a tired, overused topic. As librarians, we need to advocate for our students to get the help they need from the very start. By shifting the discourse to focus on curiosity within the classroom, providing activities grounded in low-stakes exploration, and encouraging self-reflective behaviors focused on curiosity, we can provide opportunities for more students to create their own new knowledge.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lori Townsend (external peer reviewer) and Amy Koester (internal peer reviewer) for reviewing drafts of this article. We recognize that reviewing takes a lot of time, and we are thankful for their feedback. The authors would also like to thank our Publishing Editor, Sofia Leung. Her efficiency and responsiveness were highly appreciated. Finally, we would especially like to thank the many faculty and graduate students from the OSU School of Writing Literature and Film who are always willing to consider new ideas and new approaches to our shared work. We would especially like to acknowledge Tim Jensen, Sara Jameson, Chad Iwertz, and all of the Composition Assistants who have contributed to the WR 121 curriculum.

References

Association of College and Research Libraries. 2016. “Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.” http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework.

Bowler, Leanne. 2010. “The Self-Regulation of Curiosity and Interest during the Information Search Process of Adolescent Students.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science & Technology 61 (7): 1332–44.

Collins, Robert P, Jordan A Litman, and Charles D Spielberger. 2004. “The Measurement of Perceptual Curiosity.” Personality and Individual Differences 36 (5): 1127–41.

Deitering, Anne-Marie, and Sara Jameson. 2008. “Step by Step through the Scholarly Conversation: A Collaborative Library/Writing Faculty Project to Embed Information Literacy and Promote Critical Thinking in First Year Composition at Oregon State University.” College & Undergraduate Libraries 15 (1–2): 57–79.

Head, Alison J., and Michael B. Eisenberg. 2010. “Truth Be Told: How College Students Evaluate and Use Information in the Digital Age.” Available at SSRN 2281485. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2281485.

Holliday, Wendy, and Jim Rogers. 2013. “Talking about Information Literacy: The Mediating Role of Discourse in a College Writing Classroom.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 13 (3): 257–271.

Kidd, Celeste, and Benjamin Y. Hayden. 2015. “The Psychology and Neuroscience of Curiosity.” Neuron 88 (3): 449–60.

Kuhlthau, Carol C. 1991. “Inside the Search Process: Information Seeking from the User’s Perspective.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 42 (5): 361–371.

Kuhlthau, Carol C. 1993. “A Principle of Uncertainty for Information Seeking.” The Journal of Documentation. 49 (4): 339–55.

Litman, Jordan A., Tiffany L. Hutchins, and Ryan K. Russon. 2005. “Epistemic Curiosity, Feeling‐of‐knowing, and Exploratory Behaviour.” Cognition & Emotion 19 (4): 559–82.

Litman, Jordan A., and Tiffany L. Jimerson. 2004. “The Measurement of Curiosity as a Feeling of Deprivation.” Journal of Personality Assessment 82 (2): 147–57.

Litman, Jordan A., and Mark V. Pezzo. 2007. “Dimensionality of Interpersonal Curiosity.” Personality and Individual Differences 43 (6): 1448–1459.

Litman, Jordan A., and Paul J. Silvia. 2006. “The Latent Structure of Trait Curiosity: Evidence for Interest and Deprivation Curiosity Dimensions.” Journal of Personality Assessment 86 (3): 318–28.

Loewenstein, George. 1994. “The Psychology of Curiosity: A Review and Reinterpretation.” Psychological Bulletin 116 (1): 75-98.

McMillen, Paula S., Bryan Miyagishima, and Laurel S. Maughan. 2002. “Lessons Learned about Developing and Coordinating an Instruction Program with Freshman Composition.” Reference Services Review 30 (4): 288–299.

Senko, Corwin, and Kenneth M. Miles. 2008. “Pursuing Their Own Learning Agenda: How Mastery-Oriented Students Jeopardize Their Class Performance.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 33 (4): 561–83.

Zuckerman, Marvin, and Kathryn Link. 1968. “Construct Validity for the Sensation-Seeking Scale.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 32 (4): 420-426.

I really enjoyed reading this article. Thank you.

Pingback : Cultivating Curiosity in Libraries