Conducting a Diversity Audit in an Academic Library on the Psychology, Non-Fiction Collection

In Brief

Over the course of a year, I conducted a diversity audit of part of the general nonfiction collection, specifically the psychology section (BFs) at the Charles C. Myers Library at the University of Dubuque in Dubuque, Iowa. In total I audited 1,075 books using questionnaires I developed to collect data on the science collections. Prior to this project, I was doing research for another diversity audit the library was conducting on the young adult collection, only to find that other than auditing biographies, there was no developed procedure for auditing general nonfiction. During my experience I learned a great deal of what not to do; many of my questions were too rigid, and many open-ended responses collected unmanageable data. There is a lot of room for improvement with the procedure; I wanted to write this article to highlight my successes as well as my failures, so library professionals can adapt the procedure to best fit their diversity audit needs.

Introduction & Motivation

A diversity audit is a systematic examination of a library’s collection to assess the identity representation currently found in the titles. Diversity audits yield concrete data that can be utilized to better develop collection(s) for patron use (Jensen, 2018). This project evolved from another diversity audit we were conducting on the young adult collection. The University of Dubuque has a diverse student body, and we wanted to ensure that all students could see themselves represented in the young adult collection to align with the library’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) statement: “Charles C. Myers Library strives to create equitable educational opportunities for students, faculty, and staff to cultivate a more hospitable environment that nurtures the intellectual, personal, and professional development of under-represented groups, including those historically marginalized” (Myers Library Staff, Updated 2021). Before we, my supervisor and myself, began, I was doing research on the types of data we would want to collect and how to best structure the questions to gain the most accurate representation of the current collection. It was during this research that I realized that most diversity audits were conducted on fiction collections housed at public libraries; and the audits that extended to nonfiction primarily focused on the collection’s biographies, autobiographies, and memoirs. I found Colleen Wood to be an invaluable source of information, especially Wood’s article (2021) “Counting the Collection: Conducting a Diversity Audit of Adult Biographies.” I continued to investigate how an individual could potentially audit a nonfiction collection, other than just biographies and the like, and found there was limited information on the topic, having identified a gap in the current knowledge.

Historically, the sciences have been predominantly white and male dominated fields, and this trend has been reflected in the published literature (Anderson, 2015). At the University of Dubuque, I was the Science Librarian and oversaw the development of the Psychology (BF), Science (Q), Medicine (R), and Agriculture (S) collections (letters correspond to the Library of Congress classifications). The sciences for many years have lacked diversity in their respective fields, especially in published materials, and I wanted to develop a more well-rounded collection to highlight diversity in each of the scientific collections I managed. I began to then develop a procedure to audit nonfiction collections for diversity to ‘see’ where the current print collections stood and how I could better improve them moving forward. One of my goals for the diversity audit was to ensure that the collection not only housed the prominent voices in a field (i.e. Freud, Jung, Skinner, Piaget in the field of psychology) but also collected lesser known and emerging voices as well, creating a well-rounded collection to ensure the students and faculty could conduct comprehensive research. Diversity audits are important not only to “ensure libraries are being conscientious and inclusive providing materials and resources,” but also to ensure that students and faculty can find a diverse collection of ideas and evidence to support their research (Wood, 2021) and to fulfill the library’s collection development policy: “The primary purpose of the collection is to provide students with the high-quality resources they need to succeed academically and that help shape their future as lifelong learners” (Myers Library Staff, Created 2005, Updated 2021). Overall I wanted to identify gaps in the current collection and use the collected data to support future collection development and inform future purchasing decisions.

How I jumped from the young adult collection to general nonfiction was due to a project students were doing in the Department of Natural and Applied Sciences. This project required each student to select and check-out a ‘popular-science’ title and write a report on the content. This project worked directly with the Science (Q) collection, and I began evaluating the collection to ensure that students had access to recently published titles on a variety of topics, written from multiple viewpoints. I created the Google Form questionnaires with the Science (Q) collection in mind, however, I began by auditing the psychology collection because it was the smallest of the four collections I managed. I figured I could resolve any issues with the Google Form questionnaires using the psychology collection before moving on to the larger science collections.

After completing the audit, I presented the data to my fellow library staff, for their input on future collection development. The data could then be analyzed and presented to the corresponding departments for input and recommendations for future collection development. I also wanted this process to be sustainable and adaptable for the future. Once I completed the diversity audit to identify strengths and weaknesses of the collection, I intended to use the Google Form as a ‘living document’ by adding any additional psychology (BF) titles to the audit (you can add an unlimited amount of entries to a Google Form) so it would adjust the overall collection data automatically. I could see how the collection evolved both physically and statistically.

Prediction

I predicted that a large percent of the psychology collection would be written by white, cis, able-bodied men. I predicted that diverse identities and populations would be studied within the books, but it would be through the lens of white, male authors. I also predicted that this audit would take about a year to complete. My predictions were correct. I began auditing on May 3, 2022 and concluded the audit on March 7, 2023, taking approximately 11 months to complete it.

What This Is

This project was very much a pilot study to fill a gap in the current knowledge. Finding few examples of conducting diversity audits on general nonfiction when researching, I created Google Forms to attempt to collect ‘everything,’ to see what would work and what wouldn’t. My audit was a hybrid of past fiction diversity audits and what is currently published about auditing nonfiction. In many ways, I found how not to collect data. When writing the proposal for this article, I wrote, “Failure is still data,” and I would like library professionals that are considering an audit of nonfiction to learn from my missteps and adapt the questions however needed to best audit their collection(s). It might be helpful to approach this procedure with a ‘take what you need, leave what you don’t’ mentality. Upon completion, I had two sets of data, one for general psychology nonfiction and the other for biographies within the psychology collection. Here are the links to the final data for each: General Psychology Nonfiction & Biographies with Psychology. The data collected and used in this article is secondary. I wanted to address certain limitations of the collected data and question structure using the data as reference points. In reality the data collected won’t necessarily hold much significance for another academic library. While the identified trends will most likely hold true, if another diversity audit was conducted in another library’s psychology collection, it could yield different statistics. It helped thinking while auditing that the process built is for everyone, while the data is for the Charles C. Myers Library for internal purposes. While there are data and statistics discussed in this article, please remember that these data only reflect one academic library’s print collection and could vary across institutions.

Literature Review & A Different Approach

Much of my procedure was based on Wood’s article (2021) “Counting the Collection: Conducting a Diversity Audit of Adult Biographies.” Wood began by collecting U.S. Census Data, CDC, and local data to determine the diversity makeup of the library’s community. Wood hoped to use this data to build a collection that best represented her library’s community. This is a great practice for assessing public libraries; however, census data on the national level wouldn’t accurately represent our student body data at a small, private, Presbyterian university. I forwent this step because the procedure was to capture the collection as it currently stands. However, my next step would have been: reaching out to the admissions office to gain a statistical understanding of how our student body identifies. The student body data would assist me with deciding future purchases and collection development. Also, as an academic librarian, I needed to consider courses, assignments, and research. Using publicly available data is great for public libraries but has limitations for creating an audit for an academic library focused on teaching.

Wood also discussed difficulties searching for diversity via the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). LCSHs are terms used to ‘tag’ books to ensure patrons can search for materials in a library collection in a systematic manner (Wood, 2021). As indicated by Wood, searching for diversity information via subject headings is not without challenges, including gaps in terms and tagging, embedded bias, and that the terms themselves can be outdated or problematic (Wood, 2021). LCSH terms are often not consistent enough to capture all relevant subject areas via catalog searches. This inspired Question #10, “What are the top 5 Subject Headings” (even though I ended up collecting all of the subject headings; if there were 12, I collected all 12 subject headings). Instead I collected subject headings to better assess how the psychology collection was ‘tagged.’ Question #10 set a base understanding of how the psychology titles were cataloged to help with identifying search terms to assist with research. Collecting subject headings demonstrated that even though ‘psychology’ and ‘psychoanalysis’ were the two most commonly used subject headings, these terms were not the most efficient terms to use when searching for psychology topics in the catalog. In most cases, it was more efficient to search for the secondary subject to find related titles on that topic. For example, if a student was searching for a title on psychology and genetics, it was best to search using the subject headings for ‘genetics’ because psychology was too broad a term and would generate too many unrelated results. As a reference and instruction librarian I wanted to collect this data to be able to provide better instruction on how to search for topics via the catalog for our students, aligning once again with the library’s goal of helping the students find materials to become lifelong learners.

Timeline

In November 2021, I began researching how to conduct a diversity audit. In December 2021, I shifted my focus to finding any and all published literature on how to conduct a diversity audit for nonfiction collections. From December 2021–March 2022, I researched nonfiction diversity audits. Throughout the summer of 2021, I weeded the four collections I managed (Psychology (BF), Science (Q), Medicine (R), and Agriculture (S)). I removed titles following the MUSTIE (misleading, ugly, superseded, trivial, irrelevant, or obtained elsewhere) guidelines, focusing on ‘ugly’ and ‘obtained elsewhere.’ Specifically, I removed titles that were physically damaged (‘ugly’); and I made sure, before removal, that the content being weeded could be found in another title still found in the collection (‘obtained elsewhere’). Weeding the collection was an annual project, conducted separately from the diversity audit, but it proved to be helpful to have weeded prior to conducting the diversity audit. I not only removed damaged materials and freed-up shelf space for future purchases, but, weeding also helped me consider potential questions that could be helpful when developing the Google Form questionnaires. For example, I added a short answer question for collecting editor information when a title had no author. I also added a question asking whether the title had a religious viewpoint because I found when weeding that much of our collection does. Titles having a religious viewpoint was not surprising because the University of Dubuque was founded in 1852 as a Presbyterian institution, affiliated with the Presbyterian Church. The ministry and divinity students often used the print collection, and adding this question could help me identify gaps in the collection regarding religious topics intersecting with psychology. It was my hope that I could develop the science collections not only to benefit their corresponding majors but also the entire student body.

Procedure/Materials

The materials used included: a laptop with wireless connection, a Google account to access Google Forms, which I used to collect the data, a book cart for auditing in the stacks, and a personal journal to keep track of notes, edits, and thoughts throughout the process. The journal was crucial to the procedure because every time I came across an issue, I wrote out my thought process on how to alleviate the issue. If editing the form was required, I noted why I changed the form and the date on which I created the edit. I also kept anecdotal notes about the process that would help me in the future, if I chose to do another audit. The journal enabled me not to lose my train of thought for an entire year’s project; even after a three month hiatus when the fall semester became too busy to audit on a daily basis, I could still pick up where I left off without losing any insight into the process.

My supervisor and I often discussed how our diversity audits were proceeding differently. Her audit, focusing on the young adult collection, could be done primarily online without handling the physical collection. This was not the case for auditing nonfiction, especially the older titles. When auditing a book, I needed to flip through each book to find much of the data. There is so much information that only exists on the shelves, between the pages of the books, that does not exist anywhere online. Being able to handle each book was crucial to the process, hence, requiring the book cart to stand in the actual stacks or bringing a cart of books with me to my office. To gain an understanding of the title’s content I read the cover, spine label, title page, table of contents, and list of indexed terms. Searching for titles online was often a fruitless endeavor because titles were often vague, misleading, or shared common terms with many other titles. Many authors do not have biographies anywhere outside of the blurbs on the back of the jacket covers. I searched our catalog for each book. This way, I could copy and paste bibliographic data directly into the Google Form to save time. Even the record pages in the library’s catalog often have minimal data, especially for the older titles. To gain more understanding about the authors, I read through the author(s)’ biographies (if applicable), dedication, and acknowledgements, and also did a quick Google search for each author to supplement biographic data, because most information in the author’s biography sections was educational and professional accolades and did not provide personal data. I attempted to make a list of titles, but I had to make so many assumptions about the content without the physical book to flip through. This definitely made the process slower, because each physical item needed to be evaluated, but this step was necessary to collect the most accurate data.

Psychology

There were many trends I noticed while collecting diversity data for the field of psychology. Please note, these trends were documented in only one academic library’s collection and may vary across institutions. Anecdotally, I noticed that the field of psychology often deals with binaries of information. The most common binaries studied were men’s psychology compared to women’s psychology, and Black individuals’ psychology compared to white individuals’ psychology. Asian populations were often a specific focus of a book and were often studied alone, as in the entire title focused on Asian individuals’ psychology. The psychology of heterosexual men was compared to the psychology of gay men. Gay women were rarely discussed. Many titles focused on two aspects of a topic and compared them to each other. These three binaries were the most common I found in the collection. Another observation was that when books discussed ‘ancient’ contributions to the world, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East were mentioned most frequently, and the published data often omitted Africa’s and South America’s contributions.

The field of psychology is not devoid of female professionals, however women’s contributions were overshadowed in the published literature. It was difficult to find information on women psychologists despite women being prevalent in the collection as authors. According to the data I collected, between 1900–1950 0.76% were written by women authors, between 1951–2000 39.84% were written by women authors, and between 2001–present 58.23% were written by women authors. (Please remember that these statistics only represent the print collection of one academic library and may vary by institution.) There were often Wikipedia pages for men psychologists but far fewer for women psychologists. In most cases, I learned the most information about female psychologists from their obituaries published online. Their obituaries were the first and only times their life’s work was recognized and written about. Other instances of women’s contributions to psychology include anecdotal statements about the women in the dedication sections. For example, author Roger G. Barker’s (1903–1990) wife, Louise Shedd Barker (1908–2010 estimated), collaborated on much of his research; and author James Olds’s (1922–1976) wife, Marianne E. Olds (1927–2014), assisted and supported him in the lab. These are just two examples and both were found in the authors’ biographies and book dedications. In the acknowledgement sections, many male psychologists wrote that they married their female classmates or fellow professors where they worked, indicating the women were educated and working in the field of psychology without the same recognition received by male psychologists.

Accessible equivalent of this figure.

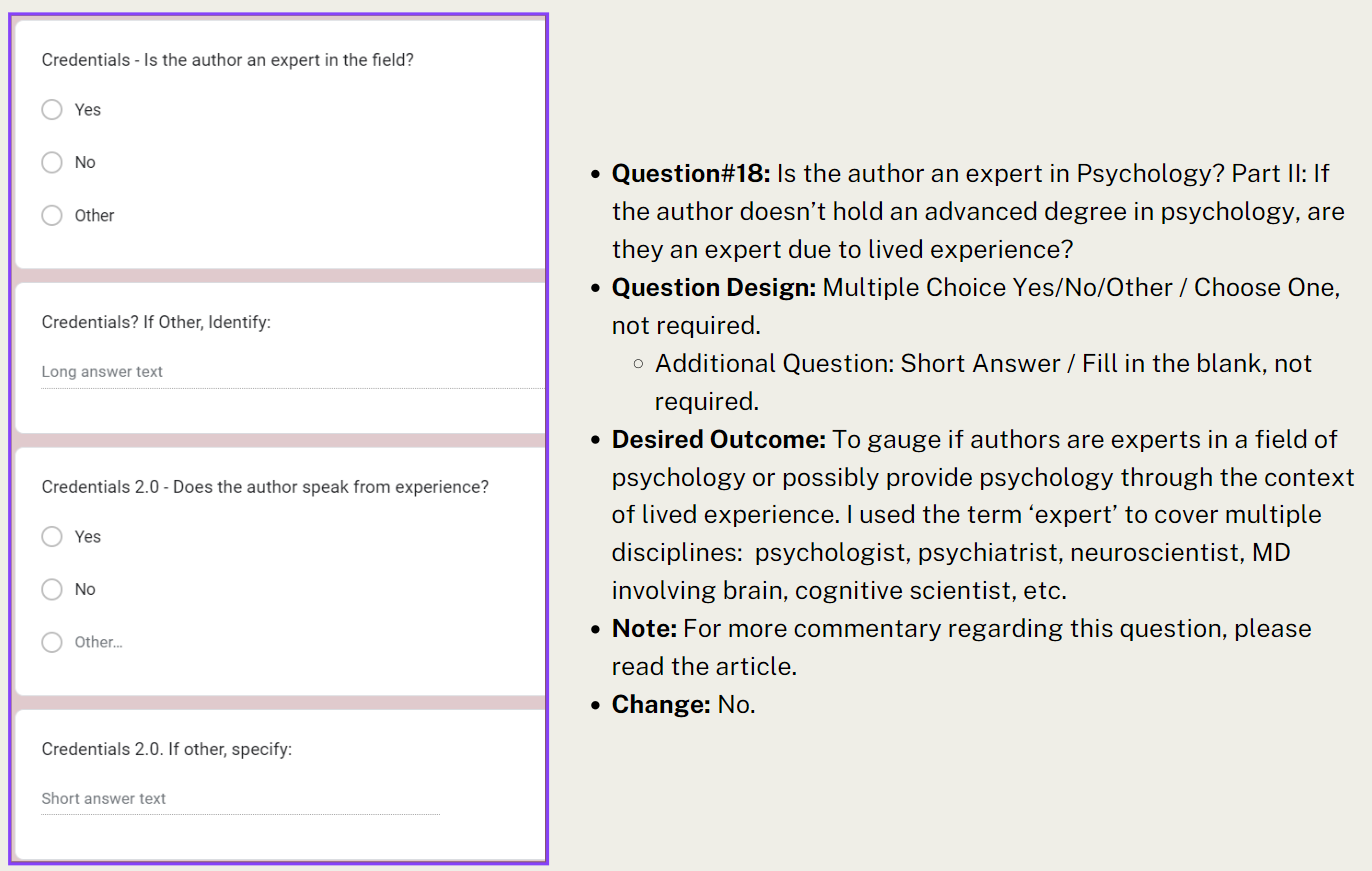

Question #18, “Is the author an expert in the field or does the author speak from experience,” highlighted this issue well. My rationale for adding this question was to gauge what percent of the collection was written by experts versus written by nonexperts. I considered anyone with an advanced degree in the fields of psychology, psychiatry, brain health, neuroscience, holding a medical degree, or cognitive scientists, etc. to be experts within the field of psychology.

I also created an additional part to this question, “Does the author speak from experience?” I wanted to capture any authors that may not necessarily have an advanced degree, but could still be considered experts due to lived experiences. For example, climate change disproportionately affects communities of color, so an author may not hold an advanced degree, but that doesn’t mean that individual is not an expert regarding climate change if they have advocated for their community or studied how it affects their towns/cities. Part I was designed to capture an author’s professional and academic credentials, and part II was designed to capture authors with lived experience that enabled them to discuss the topic from a different perspective.

What the data demonstrated is that even though women authors comprise a much smaller percentage of the collection, when it comes to holding advanced degrees in the field of psychology it was almost a 50/50 split between the two binary genders. I collected 495 ‘yeses’ for this question, so 495 individuals held advanced degrees in the field of psychology. Of the 495 individuals, 151 of them were women (30.5%), and 374 of them were men (75.5%). This data alone could lead the audience to believe that less than one-third of the women in the psychology collection hold advanced degrees; but when these numbers are compared to the entire collection (all 1,075 titles), they demonstrate a very different story. I collected data for 743 male authors during the entire audit. 374 of those men held advanced degrees, demonstrating that only 50.2% of the collection was written by male experts. I collected data for 303 female authors during the entire audit. I found that 151 of these women held advanced degrees, demonstrating that 49.8% of the collection was written by female experts. When looking at the entire collection, even though there are fewer titles written by women authors, just as many women were experts in the field of psychology.

The statistical breakdown:

When calculating based on ‘yes’ responses for question #18:

- 75.5% Men = experts in psychology (374/495×100)

- 30.5% Women = experts in psychology (151/495×100)

When calculating based on entire psychology collection:

- 50.2% Men = experts in psychology (374/743×100)

- 49.8% Women = experts in psychology (151/303×100)

I also noted that authors were not necessarily experts in psychology but were often experts in whichever field intersected with psychology. One example is Freud and philosophy: An essay on interpretation (1970) written by Paul Ricoeur. Paul Ricoeur was a distinguished French philosopher, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Another example is Figments of reality: The evolution of the curious mind (1997) by Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen. Stewart is a mathematician and Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at the University of Warwick, England, and Jack Cohen was a reproductive biologist. The majority of the psychology collection was written by experts in their distinct fields, however, their fields of study may not have necessarily been psychology.

The inverse of this was trying to gauge expertise in certain subtopics, like self-help books. It was difficult to find an individual’s qualifications for these themes. Many authors have claimed to have discovered the ‘best’ way of living or layout groundwork for ‘living authentically,’ but does being a ‘life-coach’ make someone an expert or did that lifestyle work for that individual, and now they want to sell it? The psychology section has taught me that people can literally be an expert in anything: ‘world’s leading expert on human potential’, ‘billionaire,’ and ‘anarchist-activist’ were all self-identified professions.

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939)

Freud created many dilemmas while auditing because there is so much content on his life and work; he did not fit neatly into the multiple choice questions I designed. But these dilemmas helped shape my thinking on how to collect data that doesn’t necessarily fit well into defined categories and forced me to ask myself what I wanted to learn from this audit. I struggled knowing how specific to be. I used the index of a book to identify specific topics discussed and often found that diverse content may only be discussed on a page or two. Titles written by or about Freud highlighted this issue and helped me decide only to collect diverse content data if the information pertained to at least a chapter of the book. Freud discussed many topics throughout his life’s work (homosexuality, bisexuality, women, race, etc.), but in the published literature, these topics often only were written about on a few pages of the book. His writings on these various topics were often not the main focus of the book, and therefore I did not always collect this diverse data because I wouldn’t recommend a title to a student or faculty member doing research on a topic that’s only discussed on a few pages. For example, if a book only discussed bisexuality on one to a few pages, I would mark this title as ‘no,’ for my audit when determining if the title discussed the LGBTQ+ community within their research or case studies (Question #28) because if the topic wasn’t discussed for at least a chapter of the book I wouldn’t recommend a book to students or faculty doing research on bisexuality and psychology. Throughout the audit I collected data with the mindset of recommending titles to students and faculty for research purposes. I used Freud as an example because his writings helped me adopt this practice of determining when to collect diversity content data, but this was true for many titles; the titles would mention a diverse topic on only a page or two, and auditing Freud helped shape my thinking of how to collect data that didn’t fit into checkboxes. I justified collecting diverse content data based on quantity found within a title because titles that were published more recently often still discussed the historical context of that topic. Recommending a title with a topic that was discussed for at least an entire chapter still enabled students to gain a broader understanding of the topic because the topic was discussed within the larger field of psychology.

Freud also helped me figure out how often I should collect an author’s personal data. I decided to collect the authors’ diversity data, other than gender expression, only once because I didn’t want to misrepresent the statistical data collected; meaning, Freud was the author of 32 books in the collection and I only collected his race/ethnicity data once, so the data only showed information for one Austrian psychologist instead of data misrepresenting that there were 32 different Austrian psychologists.

Collecting personal data in this manner also highlighted that the questions created were designed to collect diversity data by the standards of today and could flatten historical differences of certain data. For example, I had separate questions for an author’s race and religious beliefs, when in a historical context, these two aspects of identity may not have been separate. Historically, Freud’s race was Jewish and Austrian as determined by himself and social standards that considered Jewish individuals as ‘not-white.’ According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center (2020) “92% of U.S. Jews describe themselves as White and non-Hispanic.” My audit was designed to collect data that meets today’s social standards because my goal was to collect data that students would see when they approached the science collections. By today’s American standards Freud could be considered ‘white’ even though historically this would be inaccurate. The questionnaire in many ways did not collect historically accurate data, but collected data that students would assume when browsing the collection. Social standards evolve and will continue to do so. This diversity audit functioned like a cross-sectional study (an observational study that analyzes data from a population at a single point in time). It collected data in 2022–2023 by 2022/23 standards and the social standards will again change in the future.

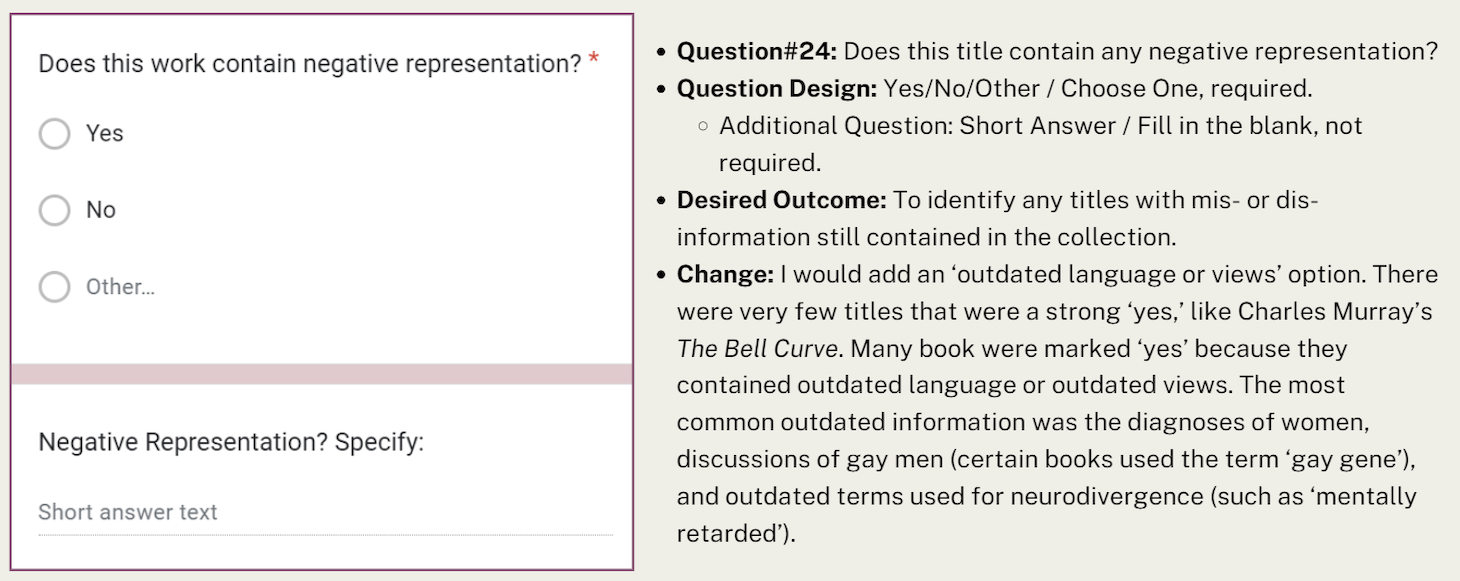

This could also be seen in Question #24: Does this title contain any negative representation? The most commonly noted ‘negative representation’ was ‘outdated views and language‘ because I created the audit using today’s standards. Many titles in the psychology collection used language that by today’s social standards would be considered outdated and potentially offensive (for example, a few titles used the term ‘gay gene’ when diagnosing gay men or many titles used the term ‘mentally retarded‘). This language is outdated by today’s standards but at the time when these titles were published this was the common vernacular. And if an audit is conducted 30 years from now, much of our language would be considered outdated because of the constant evolution of standards.

Challenges

The main challenge for the project was that the Google Form and questions were designed for the ‘life sciences;’ however, I first used the psychology collection as practice. Many of my questions were designed for topics like climate change or physics and not specifically designed for measuring the sciences rooted in humanity, like psychology. The questions would need to be developed further for the social sciences. This procedure ended up collecting a lifetime’s worth of personal data for many authors, but a lifetime’s worth of data does not fit neatly into a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ binary in the majority of cases. Many of my questions are too stagnant or static. For example, an author’s socio-economic or disability status may be fluid throughout a lifetime, and doesn’t fit into a yes/no binary. Over time definitions and conceptions of statuses like socio-economic and disability status can change as well, making it difficult to classify these into quantifiable data. I often asked myself, why does life not fit into the clean, organized boxes I created, highlighting that even though I spent weeks mapping out the information I’d like to collect, these books and lives are complicated when trying to quantify them.

One thing I constantly needed to remind myself was not to make assumptions; to only record diversity data that was clearly defined by text. For example, there were many authors on whom I could not find any personal data. All I would have is their name. I often found myself trying to make assumptions about their identity just based on their names (e.g., whether or not an author was male or female) but would hold off in an attempt not to infuse the data with my personal bias. This happened many times. I would find breadcrumbs worth of information, and my brain would want to fill in the rest of the picture, but to collect the most accurate data, I refrained from adding data which was not clearly defined by text.

I had to remind myself that an author’s life work/specialization may not be the content of the book in front of me. Many times while researching an author I would note that they specialized in XYZ, but the book may have been about ABC. I collected the authors’ personal data prior to the content’s diversity data, so it was easy to assume while looking up information about the author, that the book would focus on that author’s specialty, but often this was not the case. It was easy to lose sight and accidentally attempt to audit based on webpage content versus the actual content of the book. I also noticed, while typing my notes, I spent a lot of time falling down rabbit holes when searching online for author content or reading more than necessary from each book. I justified this practice because I wanted data that was tied to field relevance. I wanted to provide context to the data, so it wasn’t just numbers with no connection to the field of psychology. But at the same time, it ate a lot of my time, and this process was not as efficient as it could have been. The Charles C. Myers Library houses a collection of over 180,000 print titles. The psychology collection represented just .6% of the entire print collection (1,075/180,000×100). Less than 1% of the collection took me almost a year to audit; my goal was to calculate what portion of the psychology titles would be equivalent to the statistics I collected during the audit. That way I could use this found number of titles to audit the other collections I managed because the Science, Medical, and Agricultural sections were much larger than the Psychology section. This would ensure I could collect accurate data more efficiently, moving forward.

Specific Question Commentary

The majority of the questions I designed collected data that worked well. There were a few questions that, if I were to conduct another audit, would need to be edited or adjusted.

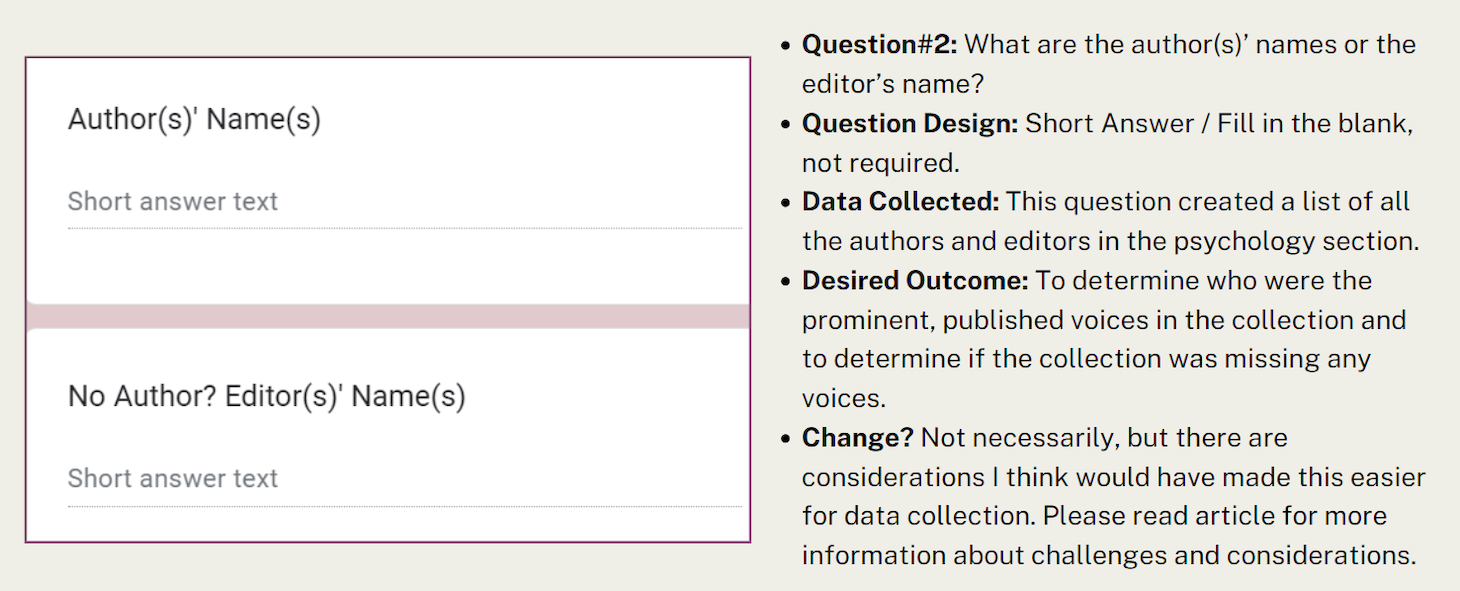

Accessible equivalent of this figure.

Question #2: “What are the author(s)’ names or the name of the editor?” I wouldn’t change the question or its design, but there are certain circumstances I wish I had considered before auditing. Many titles had 50+ authors. In these instances, I wrote “58 authors” or “56 authors” in the short-answer response. These responses were not helpful when analyzing the data. Prior to beginning I should have made a plan for when there were many authors (more than two or three authors). I also wanted to be mindful not just to audit the first author because older editions of the American Psychological Association citation style required the author’s names to be in alphabetical order, and only auditing the first author would favor/distort my data towards people with names at the beginning of the alphabet. If there were two authors, I attempted to audit both, but down the line that created issues discussed later in the article. In the future, I would add an additional question, “Does this title have multiple authors,” and the options would be yes/no, to identify which titles would have more than one author’s personal data. I ended up writing ‘multiple authors’ as a way of uniformity in my responses, but it was only a Band-Aid fix.

Accessible equivalent of this figure.

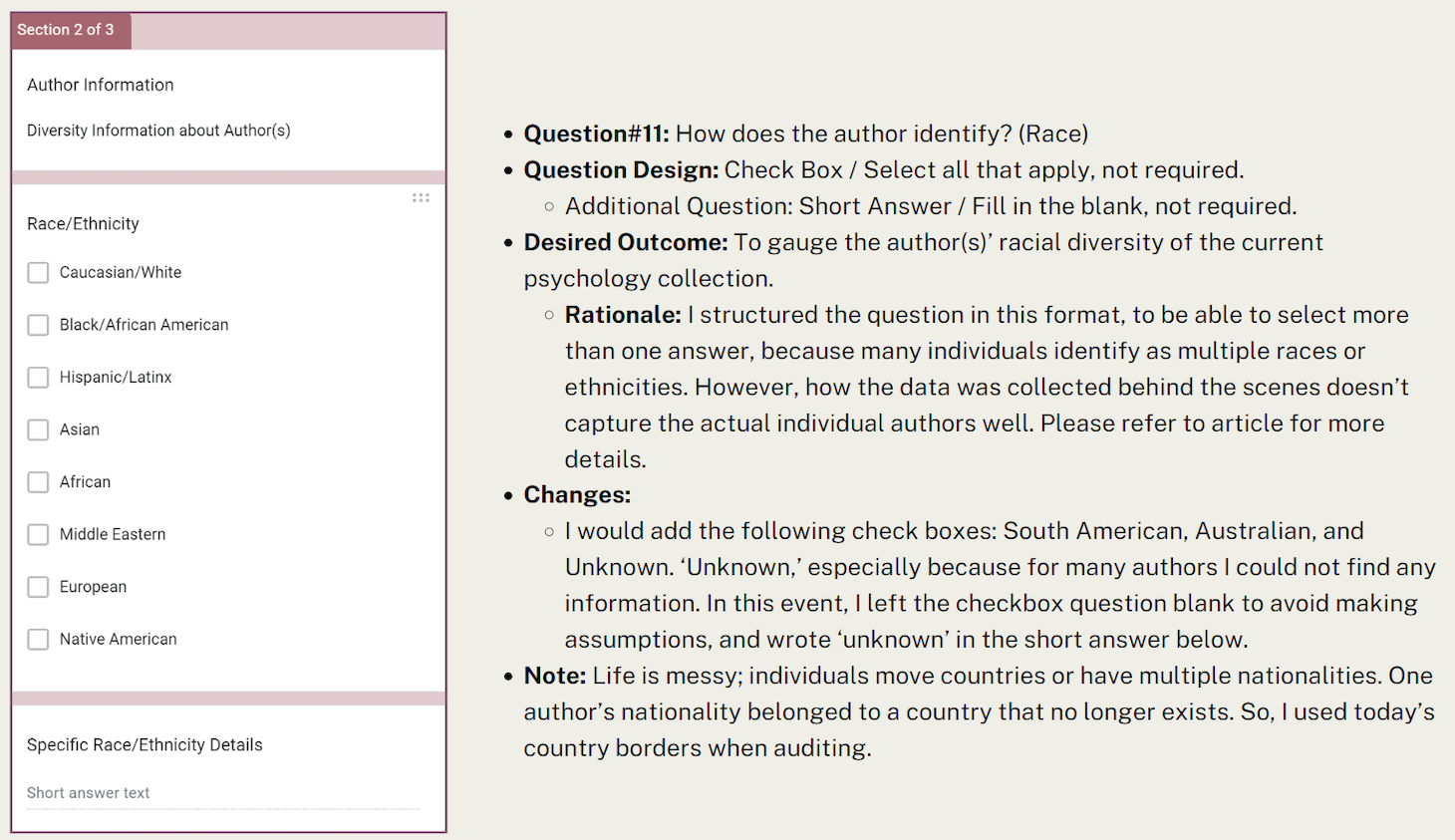

Question #11: “How does the author identify; race and ethnicity?” The structure of the question, check box, select all that apply, worked for the majority of the authors because the majority of authors identified as one race/ethnicity. However, it was not conducive to collecting racial and ethnicity data for authors that identify as more than one race/ethnicity or if the title had multiple authors of the same race/ethnicity.

When the data was collected behind the scenes in the Google Form, it counted each check-box as a one-count; meaning, if an author identifies as both Black and Asian, I could select both checkboxes, but behind the scenes it didn’t count them as one individual that identifies as both, it counted them as two individuals, one Black and one Asian. This is why I had more racial and ethnicity data for certain populations than I did authors.

This question also proved difficult when collecting racial and ethnicity data for multiple authors when they all identified as the same race. The most common scenario was multiple authors that all identified as white. So, even though according to the data, white individuals comprise 85.6% of the collection, this percentage should actually be higher because I could only collect the racial data for one author, even though, on some occasions there were multiple white authors associated with a title. I don’t believe this skewed the data too much because only a small percentage of the psychology section was written by multiple authors. My workaround for this situation was to write “whitex2” or “whitex3” in the short answer response and adjust the numbers at the end. That is why the pie chart in my slides reads differently than the bar graph that was collected from the inputted data in the Google Form.

I deduced an author’s identity based on the data I found on various sources; the most common were Wikipedia, university faculty websites, personal websites, and obituaries. I searched these and other sources of information to see if it clearly stated the author’s race and ethnicity anywhere. The biography blurbs on the back of jacket covers often excluded personal data and focused on academic and professional accolades. This method of collecting diversity data via external sources often written by individuals other than the author themselves is not without potential misinformation or personal bias on my part, the collector. One way to mitigate personal bias was not to assume any aspects of an author’s identity that were not clearly stated. One of the changes I would make to this particular question is adding an ‘unknown’ option.

I found there was a void of information on authors that published between the years of the 1970s–1980s. Prominent, well-known authors have most of their lives recounted in Wikipedia pages and more recent authors all have personal websites, podcasts, TedTalks, etc.; their information is very accessible online. But there were many authors about whom I couldn’t find any personal data and did not want to make any assumptions regarding race or ethnicity. Initially I had this question be ‘required’ but removed that requirement due to the fact that I sometimes could not find this data; in this case I left it blank and moved on to the next question.

Accessible equivalent of this figure.

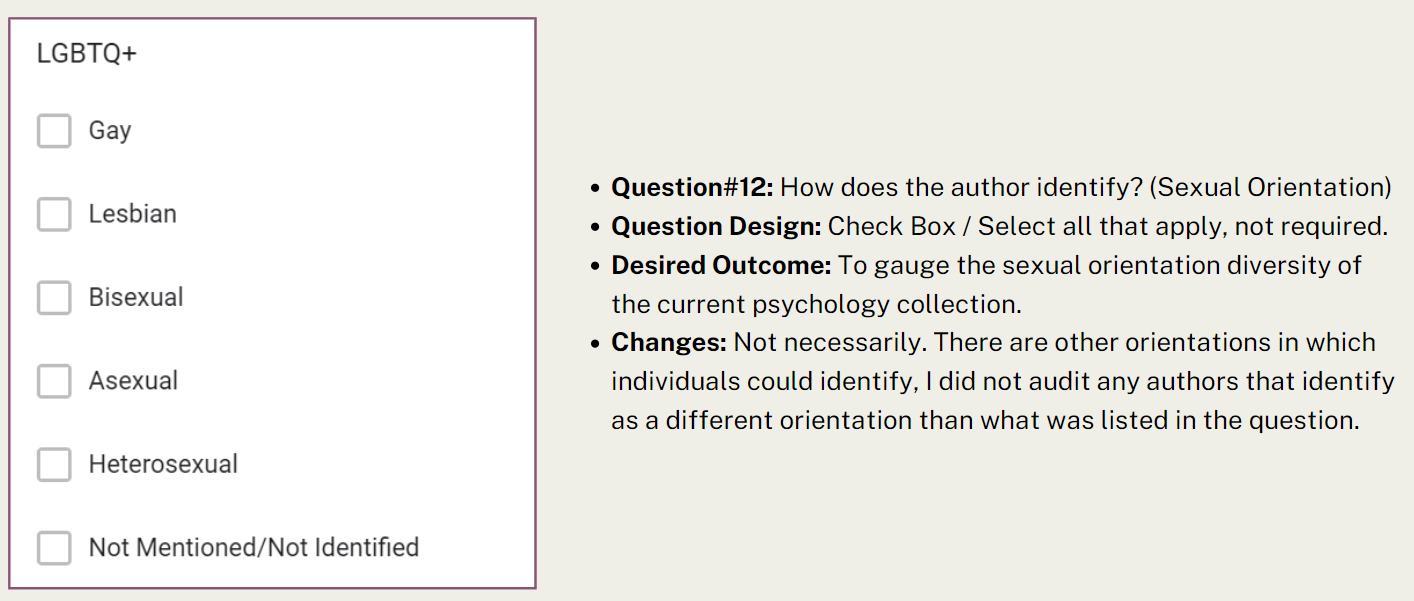

Question #12: “How does an author identify; sexual orientation?” This question requires commentary on the potential for misinformation regarding authors’ lives. To find and collect this data I checked the book’s dedication and acknowledgments to see if the author was married. I recognize this is not a perfect system to determine an individual’s sexual orientation but had difficulty finding it another way. The most common scenario was male authors dedicating books to their wives or acknowledging their wives’ support in the acknowledgement section of the book.

If an individual was never married, I checked not mentioned/not identified to avoid making assumptions. The not mentioned box represented authors that never married or instances where I couldn’t find any information on the individual. Many women authors are in the not mentioned/not identified statistics. Anecdotally, it was often more difficult to find a woman’s relationship status than a man’s. Many women authors never mentioned their relationship status anywhere in their profiles, websites, etc., while male authors were much more open about being married.

It’s important to remember that there is a lot of ‘room’ in these selected answers, especially in ‘not mentioned’ and ‘heterosexual.’ Many authors lived during a time when same-sex relationships were stigmatized and/or illegal, so the data collected for this question only portrays static data that may not necessarily accurately portray the entire picture. Many individuals could identify as bi/ace/gay but be in a heterosexual relationship due to social structures during the authors’ lifetimes.

Accessible equivalent of this figure.

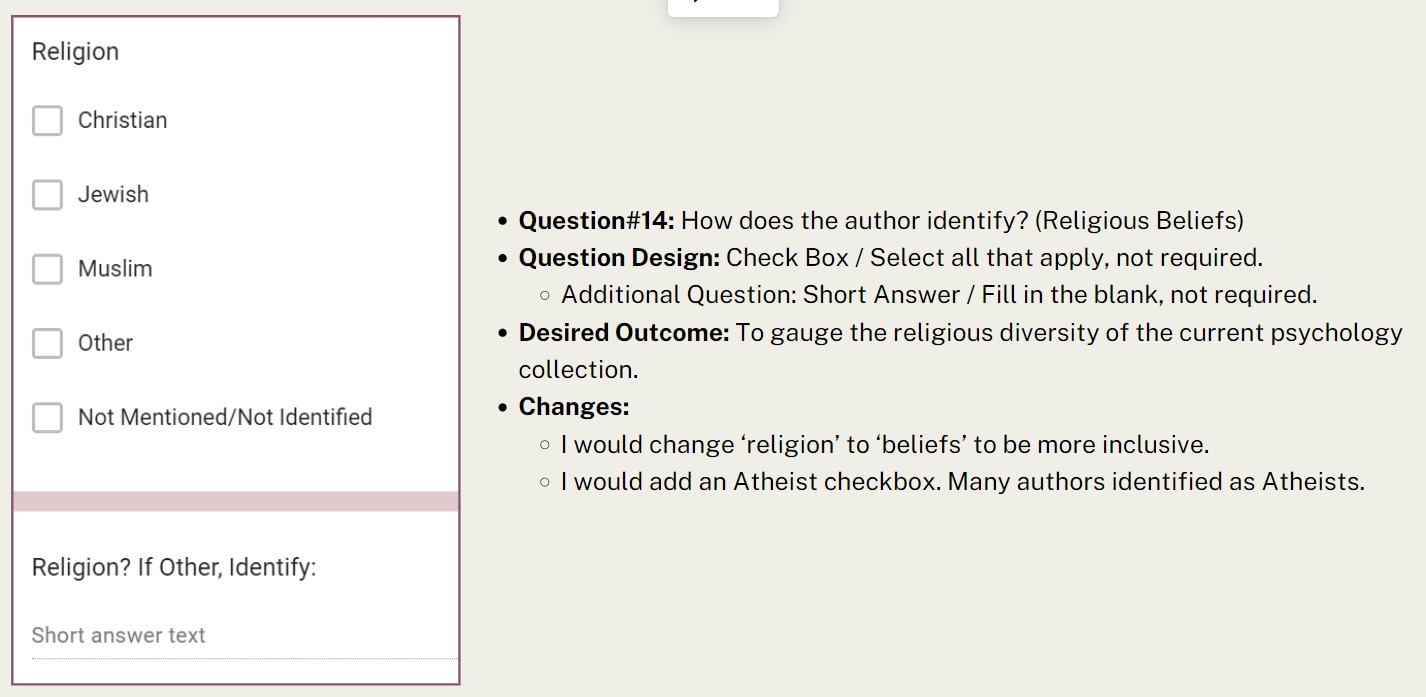

Question #14: “How does the author identify; religious beliefs?” This is another question that requires a bit of commentary. This data was difficult to collect accurately because an author’s beliefs can be, and often are, fluid throughout their lives. Many authors were raised with specific religious beliefs convert to a different religion later in life, practice multiple religions at once, or renounce religion altogether. The religious beliefs of peoples’ lives is not easily calculable with checkboxes. It should also be noted that the collected data represents the author’s adulthood beliefs. If an author was raised Jewish as a child and then became an Atheist as an adult, I counted them as ‘other’ and wrote ‘Atheist’ in the short-answer response. This is another question where there is a lot of ‘room’ within ‘not mentioned/not identified.’ An individual could be a devout Buddhist, but it’s never mentioned in their biographical data, therefore, it’s not represented here.

Accessible equivalent of this figure.

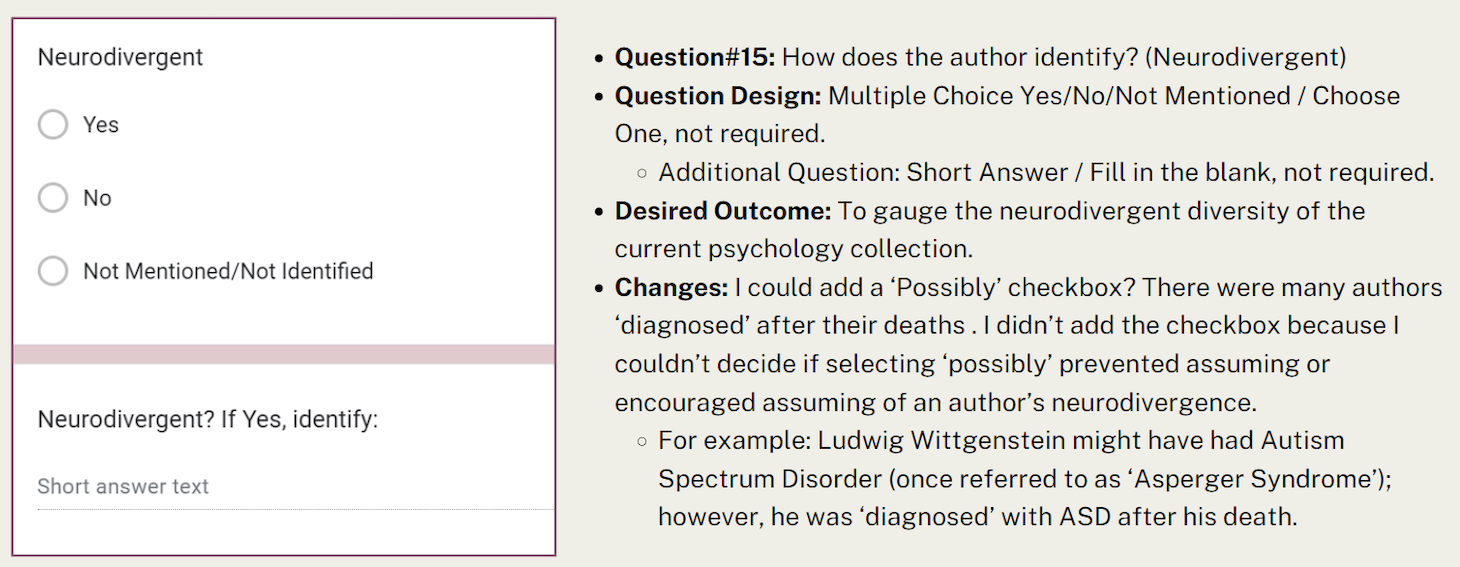

Question #15: “How does the author identify; neurodivergency? This question was another difficult one. There are many assumptions about authors, especially the well known voices in psychology. For example, many suspect Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) of being schizophrenic, but he was never diagnosed during his lifetime. One source claimed Jung heard voices and experienced visions and that even Jung himself worried about having schizophrenia. However, other sources claimed he induced these visions and voices himself to find a deeper version of himself. In this instance, I marked Jung as ‘no’ because it wasn’t a definite ‘yes,’ and it was mentioned so I couldn’t select ‘not mentioned’ either. Many individuals were ‘diagnosed’ after their deaths; I did not count these because while there may have been speculation, I didn’t want to collect data based on assumptions and not official medical diagnosis (even though medical diagnosis might have been very different when certain authors were alive). I don’t have a perfect answer for this.

Accessible equivalent of this figure.

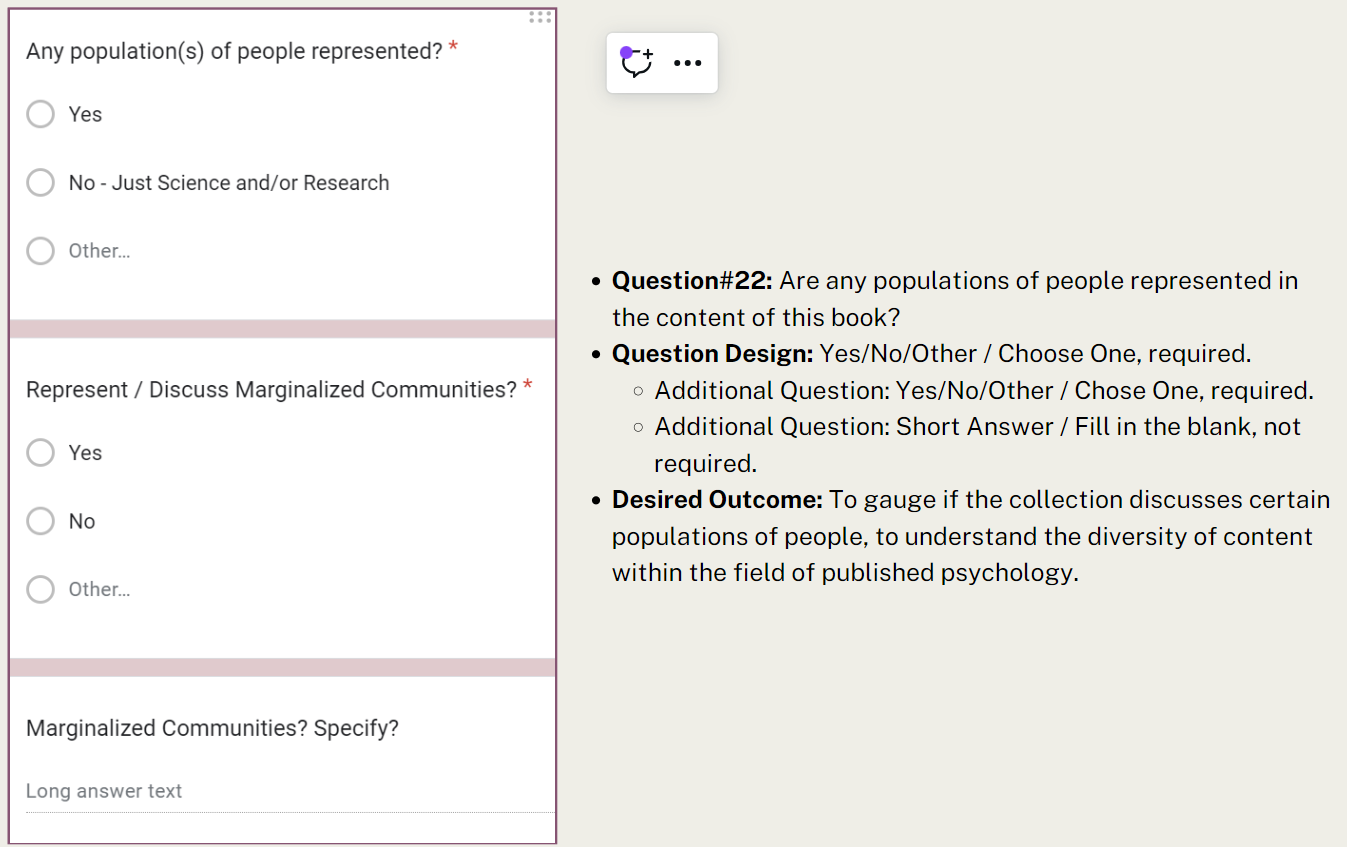

Question #22: “Are any populations of people represented in the content of this title?” I also struggled with this question. It was difficult to collect this data accurately because I designed this question with the Science and Agriculture sections in mind. This question was to help me field whether a book discussed human populations or topics like top soil. The structure of this question did not work well for the psychology section because, in most cases, psychology, the scientific study of the mind and behavior, pertained to humans. In the majority of cases, titles would discuss a specific population, culture, or nationality, but it would only be a sentence to a paragraph discussing this group of people. I counted these as ‘no,’ because I wouldn’t recommend a book to a student for research based on a sentence to a paragraph of relevant content. I only marked the titles ‘yes’ if the population was studied for at least a chapter. Most titles used population data anecdotally or as a case study to prove a larger point or support an overall thesis.

Changes I would make include adding a ‘humanity’ or a ‘population as a whole’ option. As it reads right now, by selecting ‘yes’ it sounds like the content only discusses one population that will later be specified in the part III short answer response. But many titles do not discuss specific populations; they discuss humanity as a construct or universal abstract (e.g., living with anxiety). When this was the case, which it often was, I selected ‘other’ and wrote “humanity” in the short answer response, to be able to count those when analyzing the data.

Accessible equivalent of this figure.

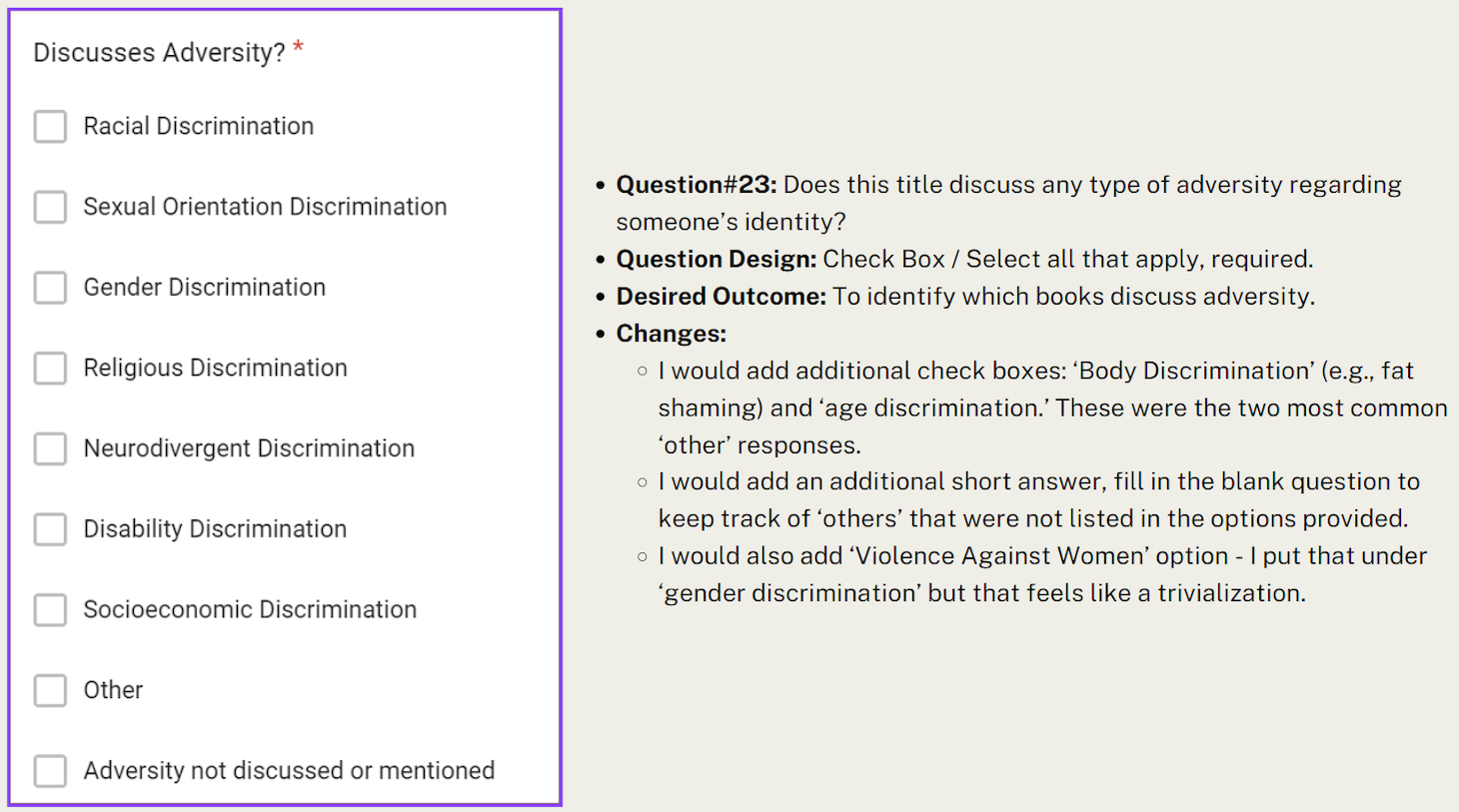

Question #23: “Does this title discuss any kind of adversity regarding someone’s identity?” I often found myself questioning the difference between adversity, discrimination, and challenges when trying to answer this question. Many books mentioned difficulties of being dyslexic without necessarily mentioning adversity or discrimination. However, the difficulties mentioned are often due to society not being accommodating enough for those experiencing dyslexia. I ended up selecting ‘neurodivergent discrimination’ because not being accommodating would count as discrimination.

Accessible equivalent of this figure.

Question #24: “Does this work contain negative representation?” When collecting data for this collection I checked the book’s chapter titles and the index list and flipped through the pages to find any images. I found that many titles had outdated language and outdated views, as indicated by the screenshot above. Due to the nature of how I searched for this information, I could have missed a lot of outdated views and language so the statistics in the linked slides could be conservative. However, I could not simply weed every title I found with outdated views and language because these outdated views were often the basis for the field of psychology, and we (universally) need to understand where we (as society) have been to not repeat dangerous practices and move the field of psychology forward. Also, students need to be able to think critically about information, questioning why certain practices were once acceptable and understand how our psychological practices have evolved.

I would edit this question to have another bubbled choice that stated ‘outdated views and/or language’ because simply selecting ‘yes’ didn’t provide enough context as to what was problematic. What I did during the audit was to select ‘other’ and type “outdated view and language” into the short answer. The question is structured the way it is now with a yes/no/other response choices because I created this form with all my collections in mind. I think this question structure would have worked well for the Science (Q) section, but would run into the same issues in the Medical section (R) as found in psychology.

Conclusion

There is always room for improvement. As mentioned above, over the course of a year, I learned what to do as much as what not to do. This project did not happen in a vacuum. I had constant support from all the librarians. I constantly discussed the development of the Google Form, diversity audit, and how it was proceeding with my fellow library staff. They offered insight and ideas that guided my thought process to ensure the process would reflect the library’s goals. This project would hopefully benefit not only the psychology students, who were in one of my liaison areas, but also other majors and programs throughout the university.

Based on the data collected I would suggest developing the biography collection further with more voices. As of right now, the collection holds biographies from the prominent voices (e.g., Freud, Jung, or Skinner), but few others. Plus, most of the biographies about women were in the parapsychology subcollection, and there needs to be more in the general psychology section. (This collection of biographies in the parapsychology subcollection was due to students needing to research the Salem Witch Trials for a course assignment.) In the past, many titles have compared two aspects of psychology: men versus women, Black versus white, gay versus straight. I would like to focus on purchasing titles that focus on one aspect supported by research and case studies (e.g., psychology of the LGTBQ+ community without comparing this community to heterosexual individuals). It’s also helpful to see when neurodivergence exists in the current collection to fill these gaps. For example, the collection holds many titles discussing anxiety, but far fewer discussing OCD. When collecting publication date data, I noticed that the children’s psychology titles in the collection were most recently published in 2006 and could seek titles published more recently. I would also want to present this data to the psychology department to demonstrate where the collection currently stands and discuss what types of resources the faculty would like to see in the collection to support research and assignments. This was an imperfect project, and I didn’t have perfect answers for collecting data. But hopefully I have stirred ideas, and people can build upon this work to build a better diversity auditing procedure for nonfiction.

Words of Encouragement

I had a lot of doubt throughout this process, so here are some of the words of encouragement I wrote to myself that hopefully will assure individuals that want to do this in the future. I wrote many times in my journal, “Don’t let perfection be the enemy of good.” I kept delaying starting the audit because I wanted the ‘perfect’ Google Form to collect data, fully knowing that that was an unattainable goal. It might be helpful to know that you can edit a Google Form at any time, and edits do not alter the data already collected and stored in the form. It was also helpful to realize the physical collection was not going anywhere. I collected the title, author, and call number for every single title. If there were questions down the line or if I needed to double check something, I could just go to the stacks and double check. Another realization that was helpful, was the fact that the data was for myself and the library staff. Every collection of titles will be different and therefore will yield different statistical data. Realizing the data would not necessarily mean anything to anyone else or another library was helpful not to lose focus. I could explain why I did what I did to my colleagues and could stop stressing about the exact percentages. Realizing these three things helped me not to lose focus or stress too much about having the perfect set of data, because in the end there’s always a margin of error.

Miscellaneous

There have been numerous indirect benefits of conducting this audit that don’t necessarily have anything to do with the audit itself. Going through the stacks while auditing I was also able to generate title lists for future books displays, recommended readings, and content for LibGuides. While at the reference desk I have been able to recommend three titles I had already audited based on their reference questions and the students’ informational needs. I was also able to observe how patrons use the stacks. A few patrons walk the stacks for exercise, like in walking laps on a track.

I was able to find books on the shelves that had been reshelved without being checked in; their statuses were still ‘checked out’ in the catalog. Shelf reading, I was able to straighten up the physical collection.1 I was able to ‘clean up’ the OCLC records as well. There were a few titles that were linked to completely different titles in the catalog. For example, Social Amnesia by Russel Jacoby had the same summary and Library of Congress Subject Headings as Old Black Fly by Jim Aylesworth. Subject Headings were: Alphabet, Stories in Rhyme, Flies Fiction, and also Psychoanalysis History.

- I was also able to clean items out of the books. I found: a business card for dentistry school, a secret message and a spell, a CDC vaccine card (Covid-19), a printout of the catalog, an Iowadot Driver’s License renewal notice, rhubarb torte recipe, rhubarb pie recipes (in total I found 4 different rhubarb dessert recipes), assignment parameters, countless Stickies, Eleanor Roosevelt Middle School floor plans, a thank you card, a postcard, old ILL slips, insurance cards, and numerous index cards. ↩︎

Acknowledgements

With great love and adoration, I’d like to dedicate this article to Becky Canovan, who always listened and was willing to discuss this process and all its frustrations. Thank you. And all of the staff at the Charles C. Myers Library, without their support, this process and article would not exist.

I am also extremely grateful for my peer reviewers Ian Beilin and Stephanie Sendaula and my publishing editor Ikumi Crocoll. Thank you. This article would not have been possible without all your time, feedback and guidance. I can’t express how much I appreciate all your support throughout this process.

Works cited/Bibliography

- American Library Association. (2017, December 25). Collection maintenance and weeding. https://www.ala.org/tools/challengesupport/selectionpolicytoolkit/weeding

- Anderson, M. (2015). The race gap in science knowledge. Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2015/09/15/the-race-gap-in-science-knowledge/

- Fuller-Gregory, C. (2022). DEI audits: The whole picture | equity. Library Journal, https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/news/DEI-Audits-The-Whole-Picture-Equity?utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=215707081&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-_cCgmhWCgTvCguLlnCwPaGxtmAmmUjPknbCQMkWYjKbLnsfc_rm7fuklQKehzrARpZ5guzBNmXDM_QBK_G7RmkXdi22w

- Jensen, K. (2018). Diversity Auditing 101: How to Evaluate Your Collection. School Library Journal, https://www.slj.com/story/diversity-auditing-101-how-to-evaluate-collection

- Marianne Egier Olds. (2014, November 6). Marianne Olds Obituary. Los Angeles Times. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/latimes/name/marianne-olds-obituary?id=17282105

- Obituaries – January/February 2010. (2010, January/February). Farewells. Stanford Magazine. https://stanfordmag.org/contents/obituaries-4675

- Peet, L. (2022). On critical cataloging: Q&A with Treshani Perera | equity. Library Journal, https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/news/On-Critical-Cataloging-QA-with-Treshani-Perera-Equity?utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=215707081&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-_cCgmhWCgTvCguLlnCwPaGxtmAmmUjPknbCQMkWYjKbLnsfc_rm7fuklQKehzrARpZ5guzBNmXDM_QBK_G7RmkXdi22w

- Pew Research Center. (2021, May 11). Jewish Americans in 2020; Report. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/05/11/race-ethnicity-heritage-and-immigration-among-u-s-jews/

- Wood, C. (2021). Counting the collection: Conducting a diversity audit of adult biographies. Library Journal, https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/Counting-the-Collection-Conducting-a-Diversity-Audit-of-Adult-Biographies

Accessible Equivalents

Figure 1

Question 18 Description

Question 18 Text

- Question Part 1: Credentials – Is the author an expert in the field?

- Answer Part 1: Multiple choice: Yes, No, Other

- Question Part 2: Credentials? If Other, Identify:

- Answer Part 2: Long answer text

- Question Part 3: Credentials 2.0 – Does the author speak from experience?

- Answer Part 3: Credentials 2.0. If other, specify:

- Answer Part 3: Short answer text

Author’s Annotations of Question 18

- Question #18: Is the author an expert in Psychology? Part II: If the author doesn’t hold an advanced degree in psychology, are they an expert due to lived experience?

- Question Design: Bubbled Yes/No/Not Mentioned / Choose One, not required.

- Additional Question: Short Answer / Fill in the blank, not required.

- Desired Outcome: To gauge if authors are experts in some field of psychology to have published a book cataloged in this collection. I used this term “expert” to cover multiple disciplines: psychologist, psychiatrist, neuroscientist, MD involving brain cognitive scientist, etc.

- Change: No.

Return to Figure 1 caption.

Figure 2

Question 2 Description

Question 2 Text

- Question Part 1: Author(s)’s Name(s)

- Answer Part 1: Short answer text

- Question Part 2: No Author? Editor(s)’ Name(s)

- Answer Part 2: Short answer text

Author’s Annotations of Question 2

- Question #2: What are the author(s)’ names or the editor’s name?

- Question Design: Short answer / fill in the blank, not required.

- Data Collected: This question created a list of all the authors and editors in the psychology section.

- Desired Outcome: To determine who were the prominent, published voices in the collection and to determine if the collection was missing any voices.

- Change? Not necessarily, but there are considerations I think would have made this easier for data collection. Please read article for more information about challenges and considerations.

Return to Figure 2 caption.

Figure 3

Question 11 Description

Question 11 Text

- Question Part 1: Author Information; Diversity Information about Author(s)

- Answer Part 1: Race/Ethnicity; Multiple choice: Caucasian/White, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian, African, Middle Eastern, European, Native American

- Question Part 2: Specific Race/Ethnicity Details

- Answer Part 2: Short answer text

Author’s Annotations of Question 11

- Question #11: How does the author identify? (Race)

- Question Design: Check Box/ Select all that apply, not required.

- Additional Question: Short Answer / Fill in the blank, not required.

- Desired Outcome: To gauge the author(s)’ racial diversity of the current psychology collection.

- Rationale: I structured the question in this format, to be able to select more than one answer, because many individuals identify as multiple races or ethnicities. However, how the data was collected behind the scenes doesn’t capture the actual individual authors well.

- Changes:

- I would add the following check boxes: South American, Australian, and Unknown. ‘Unknown,’ especially because for many authors I could not find any information. In this event, I left the checkbox question blank to avoid making assumptions, and wrote, “unknown” in the short answer below.

- Note: Life is messy; individuals move countries or have multiple nationalities. One author’s nationality belonged to a country that no longer exists. So, I used today’s country borders when auditing.

Return to Figure 3 caption.

Figure 4

Question 12 Description

Question 12 Text

- Question: LGBTQ+

- Answer: Multiple choice: Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Asexual, Heterosexual, Not Mentioned/Not Identified

Author’s Annotations of Question 12

- Question #12: How does the author identify? (Sexual Orientation)

- Question Design: Check Box / Select all that apply, not required.

- Desired Outcome: To gauge the sexual orientation diversity of the current psychology collection.

- Changes: Not necessarily. There are other orientations in which individuals could identify, I did not audit any authors that identify as a different orientation than what was listed in the question.

Return to Figure 4 caption.

Figure 5

Question 14 Description

Question 14 Text

- Question Part 1: Religion

- Answer Part 1: Multiple choice: Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Other, Not Mentioned/Not Identified

- Question Part 2: Religion? If Other, Identify:

- Answer Part 2: Short answer text

Author’s Annotations of Question 14

- Question #14: How does the author identify? (Religious Beliefs)

- Question Design: Check Box / Select all that apply, not required.

- Additional Question: Short Answer / Fill in the blank, not required.

- Desired Outcome: To gauge the religious diversity of the current psychology collection.

- Changes:

- I would change ‘religion’ to ‘beliefs’ to be more inclusive.

- I would add an Atheist checkbox. Many authors identified as Atheists.

Figure 6

Question 15 Description

Question 15 Text

- Question Part 1: Neurodivergent

- Answer Part 1: Multiple choice: Yes, No, Not Mentioned/Not Identified

- Question Part 2: Neurodivergent? If Yes, identify:

- Answer Part 2: Short answer text

Author’s Annotations of Question 15

- Question #15: How does the author identify? (Neurodivergent)

- Question Design: Bubbled Yes/No/Not Mentioned / Choose One, not required.

- Additional Question: Short Answer / Fill in the blank, not required.

- Desired Outcome: To gauge the neurodivergent diversity of the current psychology collection.

- Changes: I could add a ‘Possibly’ checkbox? There were many authors with speculation. I didn’t add the checkbox because I couldn’t decide if selecting ‘possibly’ prevented assuming or if it was assuming of an author’s neurodivergence.

- For example: Ludwig Wittgenstein might have Autism Spectrum Disorder (once referred to as ‘Asperger Syndrome’); however, he was ‘diagnosed’ with ASD after his death.

Return to Figure 6 caption.

Figure 7

Question 22 Description

Question 22 Text

- Question Part 1: Any population(s) of people represented? (asterisked)

- Answer Part 1: Multiple choice: Yes; No – Just Science and/or Research; Other…

- Question Part 2: Represent / Discuss Marginalized Communities (asterisked)

- Answer Part 2: Multiple choice: Yes, No, Other…

- Question Part 3: Marginalized Communities? Specify?

- Answer Part 3: Long answer text

Author’s Annotations of Question 22

- Question #22: Are any populations of people represented in the content of this book?

- Yes/No/Other / Choose One, required.

- Additional Question: Short Answer / Fill in the blank, not required.

- Desired Outcome: To gauge if the collection discusses certain populations of people, to understand the diversity of content within the field of published psychology.

Return to Figure 7 caption.

Figure 8

Question 23 Description

Question 23 Text

- Question: Discusses Adversity? (asterisked)

- Answer: Multiple choice: Racial Discrimination, Sexual Orientation Discrimination, Gender Discrimination, Religious Discrimination, Neurodivergent Discrimination, Disability Discrimination, Socioeconomic Discrimination, Other, Adversity not discussed or mentioned

Author’s Annotations of Question 23

- Question #23: Does this title discuss anytime of adversity regarding someone’s identity?

- Question Design: Check Box / Select all that apply, required.

- Desired Outcome: To identify which books discuss adversity.

- Changes:

- I would add additional check boxes: ‘Body Discrimination’ (e.g., fat shaming) and ‘age discrimination.’ These were the two most common ‘other’ responses.

- I would add an additional short answer, fill in the blank question to keep track of ‘others’ that were not listed in the options provided.

- I would also add ‘Violence Against Women’ option – I put that under ‘gender discrimination’ but that feels like a trivialization because it’s so much more than a micro-aggression.

Figure 9

Question 24 Description

Question 24 Text

- Question Part 1: Does this work contain negative representation (asterisked)

- Answer Part 1: Multiple choice: Yes, No, Other…

- Question Part 2: Negative Representation? Specify:

- Answer Part 2: Short answer text

Author’s Annotations of Question 24

- Question #24: Does this title contain any negative representation?

- Question Design: Yes/No/Other / Choose One, required.

- Additional Question: Short Answer / Fill in the blank, not required.

- Desired Outcome: To identify any titles with mis- or dis-information still contained in the collection.

- Change: I would add an ‘outdated’ option. There were very few titles that were a strong ‘yes,’ like Charles Murray’s The Bell Curve. Many books were marked ‘yes’ because they contained outdated language or outdated views. The most common outdated information was the diagnoses of women, discussions of gay men (certain books used the term ‘gay gene’), and outdated terms used for neurodivergence (such as ‘mentally retarded’).

In the Library with the Lead Pipe welcomes substantive discussion about the content of published articles. This includes critical feedback. However, comments that are personal attacks or harassment will not be posted. All comments are moderated before posting to ensure that they comply with the Code of Conduct. The editorial board reviews comments on an infrequent schedule (and sometimes WordPress eats comments), so if you have submitted a comment that abides by the Code of Conduct and it hasn’t been posted within a week, please email us at itlwtlp at gmail dot com!