We Need to Talk About How We Talk About Disability: A Critical Quasi-systematic Review

By Amelia Gibson, Kristen Bowen, and Dana Hanson

In Brief

This quasi-systematic review uses a critical disability framework to assess definitions of disability, use of critical disability approaches, and hierarchies of credibility in LIS research between 1978 and 2018. We present quantitative and qualitative findings about trends and gaps in the research, and discuss the importance of critical and justice-based frameworks for continued development of a liberatory LIS theory and practice.

Disability and Conditional Citizenship

Much of the mythos of modern American librarianship is grounded in its connections to grand ideas about community, citizenship, rights, common ownership, and, in many cases, stewardship of public goods and information. Despite these ostensibly community-oriented ideals, much of the current practice of librarianship and information science (LIS) in the U.S. is also embedded with and within neoliberal social and political institutions and norms (Bourg, 2014; Ettarh, 2018; Jaeger 2014) that often tie library and information access to selective membership and “productive citizenship” (Fadyl et al., 2020), and marginalize disabled people who are considered “unproductive.” This ongoing internal conflict is reflected in perennial debates about intellectual freedom and social justice (Knox, 2020), as well as commonplace beliefs and practices about belonging and ownership in public space. Under neoliberalism, “tax paying citizens,” “dues paying members,” and “loyal customers” all claim rights and privileges denied to non-contributing “non-citizens”or outsiders. This excludes disabled people, people experiencing homelessness, teens, nonresidents, and anyone else who has not sufficiently “paid their dues.” This framework reflects the medical model of disability, which sites the locus of responsibility for cure or rehabilitation with the individual. This same value system deprioritizes community investments in libraries and other non-revenue generating information infrastructures—framing them as leisure, demanding increasing budget efficiencies and consistent positive return on investment (ROI), while engaging in “benevolent” surveillance and data collection in the name of optimization and revenue generation (Lee & Cifor, 2019; Mathios, 2019). These austerity measures often reinforce the status of disabled people as “sub-citizens” who are often denied access based on cost or inconvenience (Sparke, 2017; Webb & Bywaters, 2018), and who must often trade personal disclosures and dignity for the most basic accommodations. This effect is particularly pronounced for disabled people of color who bear the burden of multiple marginalizations across many social and technical contexts.

The Danger of Single-Axis Definitions of Disability

Without critical self-reflection and examination, and without the willingness to tease out and openly name intersections of ableism, racism, xenophobia, sexism, classism, homophobia, and transphobia masquerading as practice, policy, research and education, we continue to create and reproduce violent (and mediocre) information systems and spaces. This violence might not be explicit or intentional, but intentions are beside the point (and are frequently used to derail discussions about outcomes and the need for systemic changes). Focusing on disability as a single axis of identity effectively codes disability as White (Gibson & Hanson-Baldauf, 2019), and actively ignores the specific information needs and access issues that disabled BIPOC experience, including heightened risk for police violence, lowest rates of employment, and increased discrimination within educational and financial institutions (Goodman, Morris, & Boston, 2019). It also prioritizes White comfort over the needs of disabled BIPOC, and allows White people (disabled and nondisabled) to enjoy the fruits of structural ableism and racism without the guilt of doing explicitly ableist and racist things (Stikkers, 2014).

Disciplinary subdivisions—especially public, academic, and medical librarianship—also betray a one-dimensional understanding of what constitutes “normal” public or academic information and what constitutes special “medical” or “health-related” information. These implicit frameworks for “norms” and “pathologies,” which are based in a medical model of disability that focuses on individual impairment, cure, and accommodation, also impact the qualitative experience of library spaces for community members and library workers.

Over the last quarter of a century, disability activists and movements have challenged the primacy of the medical model, arguing for disability as a social construct, imposed by a society that values conformity over individuality (Oliver 1990; Olkin 1999). According to the social model, one is not disabled by his or her physical embodiment, but rather by a society unwilling to accept and accommodate the wide diversity of humanity. Igniting the disability rights movement, the social model served as an emancipatory force by empowering individuals to assert their rights and fight for the removal of disabling barriers (Barnartt &Altman 2001). More recently, critical disability theory, disability justice frameworks, and other disability frameworks have offered disability rights advocates and scholars a means to construct more authentic representations of disability, physical embodiment, social power structures, and intersecting identities. Both shifts could, if integrated into LIS, have profound implications for the way we conceptualize systems and services for disabled people.

Who Do We Believe? The Hierarchy of Credibility

The near-invisibility of disabled people in the research process can be attributed to what Becker (1966) referred to as a hierarchy of credibility. That is, the tendency of researchers to prioritize and amplify perspectives from those with greater institutional power and social capital over the voices and lived experiences of marginalized people. In academia, this hierarchy assigns the highest authority on information related to disability to medical professionals and other healthcare providers, parents, and additional caretakers; disabled people are placed at the bottom of the hierarchy. The regular exclusion of disabled people in positions of power in research reflects broader societal devaluation. This devaluation is evident in citation practices and research methods, such as those that assign authority to healthcare provider narratives as “expert opinions” while denigrating disabled people’s narratives as unscientific anecdotes. It is a gross understatement to say that the history of disability reflects a systemic lack of justice in American social and political systems (Braddock & Parish, 2001). Although the birth of the scientific method eventually facilitated more sophisticated biological and technical treatments and supports for many disabilities, it also established rigid parameters for “normalcy” and social aberrance, and firmly established lines dividing disability and power. These parameters persist in the current day, informing scholarship and practice that still elevate conformity to the norms established by a nondisabled white center. Simultaneously, that center reserves for itself the institutional, economic, and political power to shape norms, determine policy, establish the boundaries of “ability” and “disability,” and assign value to those categories. This hierarchy of intersectional ableism reflects the hierarchy of privilege and prerogative outlined in Harris’ (1993) Whiteness as property. We see this phenomenon frequently in discussions about disability accommodations, when nondisabled managers decide that an employee is not disabled “enough” to warrant accommodations, or that an accommodation is an “undue burden” (e.g., Pionke, 2017). The same processes that marginalize the employee also make it difficult for them to attain the career advancement needed to make those sorts of decisions themselves. Like whiteness, ableism protects itself by building social, political, and economic structures (policies, norms, institutions, etc.) that reinforce systems of privilege and exclusion. We see this in the elevation of professional training over lived experience, and parents and families over disabled individuals themselves. Research that focuses on disabled people as subjects but ignores their perspectives function to exclude them from influencing LIS practice and research in any meaningful way. It silences critique in favor of topics, frameworks, and questions designed (and often answered) by nondisabled people.

Hill’s (2013) study offers one of the few expansive reviews of LIS field’s literature on disability. Employing a content analysis of articles published between 2000-2010, Hill reported a scarcity, unbalanced, and limited scope of disability-related publications. Of the 198 articles identified, the vast majority focused on visual disabilities (41%) and non-specific, general “disabilities” (42%). Practitioner literature made up approximately 65% of the available literature. Hill described the articles as predominantly practitioner-centered expositions of how people with disabilities operate within library spaces, challenges encountered, and interventions. Hill also observed that these articles were most often written from a non-disabled viewpoint, gave minimal consideration to intervening social or attitudinal factors, and offered guidance largely lacking empirical support. Research investigations made up the remaining 35% of the literature reviewed. Of the seventy studies identified, only twenty-five solicited input from disabled people. Research involving accessibility testing commonly recruited non-disabled participants over disabled participants. Hill concluded, “Overall, there appears to be a lot of discussion about people with disabilities, but little direct involvement of these people in the research” (p. 141).

Methods

A systematic literature review was deemed most appropriate to meet the aims of the present study. As the methodological tool, the approach offers a highly structured and rigorously comprehensive process, allowing the research team to capture a bird’s eye view of the available literature, detect variance in the literature, and identify gaps in the recorded knowledge. This methodology also allows for replication and the ongoing pursuance, appraisal, and integration of new knowledge. While widely applied within medical and healthcare research, Xu, et al. (2015) report a recent rise in systematic (and quasi-systematic) reviews in LIS, and advocate for further use of the method.

Researchers conducted the systematic review between August 2018 to May 2019 using the following steps:

- Identifying research questions

- Determining criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of literature

- Establishing and implementing the search protocol

- Screening and extracting non-relevant results using inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Conduct a randomized sample selection of the literature

- Develop coding schema and establish intercoder reliability

- Review and apply coding schema

Research Questions

Building on data presented in Hill’s (2013) review of LIS literature covering a ten-year span between 2000 and 2010, this investigation aimed to establish a baseline of understanding pertaining the historic and present-day representation of people with disabilities through a systematic quantitative and qualitative examination of the LIS research and practitioner literature, guided by the following questions:

- How many articles about disability in LIS have been published in the 40-year period in question? How do LIS researchers define disability? What disability frameworks have informed LIS research related to disability between 1965 and 2018?

- What hierarchies of disability and credibility are evidenced in the literature during that period?

- To what extent are critical disability frameworks employed in writing about disability in LIS?

Inclusion Criteria

The next step was to establish distinct perimeters for the scope of literature to be reviewed. This involved discussion among the research team to develop criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of specific works. As outlined in Table 1, selection included publication date, peer-review status, presented content (topic and type of article), availability in full (either online or through interlibrary access), printed publication language, and the discipline-explicit subject heading of the journal or conference proceeding in which the article was published.

| Screening Categories | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Publication Date | Published between January 1978 and September 2018 | Published prior to January 1978 |

| Language | English | Non-English |

| Subject Discipline | Library and Information Science (LIS) | Non-Library and Information Science |

| Review Process | Peer review process for publication | No peer review process for publication |

| Article Type | Original research, viewpoint, technical paper, conceptual paper, case study, literature review, general review | Book reviews, bibliographies, editorials, posters, announcements and other brief communications |

| Central focus | Article content centers on people with disabilities | Article content contains only a perfunctory reference to people with disabilities |

| Availability | Article can be found online and in full text | Full text article is not available online |

*Publication subject discipline verified using Ulrich’s Online Serial Directory

Establish and implement a search protocol

The research team developed a search protocol for the systematic identification and extraction of literature. This included determining relevant sources, database tools, and search terminology. Sources were limited to LIS journals and conferences with established peer-review processes for publication acceptance. The team selected two bibliographic databases to conduct the search based on relevancy, coverage, and reputation: Library and Information Science Source (LISS) and Library and Information Science Abstracts (LISA). Next, the researchers developed a list of keywords by conducting an exploratory search of controlled vocabulary within each database thesaurus. These keywords were intended to capture conditions listed under “disability” within each database and to capture common disabilities that were not specifically associated with variations on “disability” (Search query 1) in each database. This meant that names of specific conditions that might be expected in discussions about disability (e.g., “Deaf” or “Blind”) might not appear in initial searches, because they were included in the results from Search Query 1. Search queries 2 and 3 were intended to expand the possible scope of the initial list, in order to capture literature on specific conditions that were inconsistently indexed as disabilities in an exploratory literature search. From this list, three search queries were constructed (Table 2) comprising: (1) the term “disability” and variations of the term in current and past practice; (2) additional specific categories of disability for expansion of results list; and (3) and disability frameworks.

| Search Queries | Query Content |

|---|---|

| Search Query 1 | disability OR disabled OR handicapped OR “differently abled” OR “differently-abled” OR disabilities OR “Special Needs” OR retardation OR retard* |

| Search Query 2 | Autism OR ASD OR ADHD OR “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” OR “Auditory Processing Disorder” OR “Traumatic Brain Injury” OR dyslexia OR (add AND attention) OR (sensory AND disorder) OR Aphasia OR Agraphia OR “perceptual disturbance” |

| Search Query 3 | “Social role valorization” OR “complex embodiment” |

Search queries 2 and 3 did not include specific categories and frameworks containing the word (or variations of the word) “disability” as it was assumed the queries would yield duplicate results captured under query 1, for example “physical disability” or “social model of disability”.

The three search queries conducted on each database that used the available filtering functions to narrow the scope of literature based on established inclusion and exclusion criteria yielded 17,632 references. Next, reference results were exported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and displayed horizontally (one reference per row) and organized vertically into columns (by author, article title, publication date, etc.). Duplicate references were identified and extracted and using conditional formatting and customized sort & filter functions. Upon completion of this process, 7859 duplicate articles were removed from the literature set and 9773 references remained. Table 3 presents an aggregate view of this process.

| Database | References Downloaded | Duplicates Identified Within and Between | Prescreened References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library and Information Science Abstracts(LISA) | 13445 | (7859) | 7955 |

| Library and Information Science Source(LISS) | 3562 | 1620 | |

| Library and Information Science Technology Abstracts (LISTA) | 625 | 198 | |

| Total | 17632 | (7859) | 9773 |

Screen and extract non-relevant reference data using inclusion/exclusion criteria

The next phase involved screening references for the purpose of extracting all non-relevant references from the literature set. As previously outlined in Table 1, screening categories included the article publication date, printed language, publication discipline, review process, article type, online availability, and central focus. While database filter functions were activated during the initial query search process, manual screening proved necessary to ensure inclusion and exclusion criteria were met. A summary of the process can be found in Table 4, followed by detailed descriptions of the screening categories.

| Screening Categories | References Removed | References Remaining |

|---|---|---|

| Publication date | 0 | 9773 |

| Language | 223 | 9550 |

| Subject discipline | 2382 | 7168 |

| Review process | 21 | 7147 |

| Article type | 927 | 6220 |

| Topic relevance | 5400 | 820 |

| Online and full text availability | 161 | 659(remainder requested via Interlibrary Loan) |

Publication Date. The first step in the screening process was to organize the literature set by publication year and scan for articles published prior to January 1978. No articles were identified for extraction during this process.

Printed Language. To identify and extract non-English publications, the language column of the literature set was alphabetized, thereby grouping publications by language for bulk removal. In some cases, languages were displayed in brackets following the article’s title (i.e. “Title [Hungarian]”). These titles were identified using Excel’s “Find” function, and searching for brackets. The remaining non-English titles were identified individually throughout the screening process. The researchers removed a total of 223 non-English language articles, leaving 9550 references in the set.

Subject Discipline. The literature set was then screened to identify and remove publications (i.e. journals and conference reports) from outside of LIS. To accomplish this step, references were grouped by publication title and screened using Ulrich’s Online Serial Directory to verify each publication’s subject heading. Publications without LIS subject headings (e.g., “Library and Information Science” or “Information Science and Information Theory”) were removed from the literature set. A total of 7168 remained after the removal of non-LIS sources.

Review Status. In addition to extracting non-LIS publications, Ulrich’s Online Serial Directory was used to determine a publication’s review process. Works published in sources without a peer-review process were removed, accounting for 21 references with 7147 references remaining in the literature set.

Article Type. References were then sorted and categorized by article type, as determined by the established exclusion criteria. This task was completed using Excel’s “Find” function to search the title and abstract columns. Table 5 provides a list of terms employed in the search. References identified through this process were then screened by eye to confirm or reject group identity and color-coded accordingly. Nine hundred twenty seven references met criteria for exclusion from the study and were removed. A total of 6220 references remained.

| Content Type Excluded | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Book reviews | “book review”, “is reviewed by”, (name of reviewer) “reviews the book” |

| Bibliographies | “bibliograph*” |

| Posters | “poster” |

| Editorials | “editor*” |

| Introductions | “introduction” “special issue” |

| Brief communication | “notes” “memorandum” “announcements” “news brief” “from the field” “article alerts” |

| Conference Proceeding, Misc. | “schedule” “agenda” “overview” “conference” “meeting” “summary” “minutes” “proceedings” |

Central focus. Remaining references were then screened to determine topic relevance – that is, articles predominantly centering on disability and disabled people. This entailed open coding a subset of the data to create an extensive list of disability-related search terms, including disability classifications, frameworks, degree of impact language, intervention-related terms, and people-first language (Table 6). Again, the purpose here was to avoid excluding any article focused on disability, but to begin to weed out articles that were not focused on human disabilities. Additionally, we attempted to stick as closely as possible to an emergent characterization of disability as from the literature, rather than imposing our own definition.

| Terms | |

|---|---|

| Disability Classifications | ADHD, Alzheimer, apraxia*, apsperg*, acquired brain injury, ASD, Attention, autis*, behavior challenges, blind, brain damage, cognitive needs, deaf, delay*, dementia, depress*, development*, disab*, disorder, dwarf*, dyslexi*, epilep*, gait, handicap*, hearing, impair*, little people, low vision, memory, mental illness, mobility, limitations, motor skills, multiple sclerosis neurodiv*, palsy, PPD-NOS, quadri*, retard*, sensory, special needs, spinal muscular atrophy, stammer, stutter, syndrome, TBI, tic, traumatic brain damage |

| Degree of Impact | mild, moderate, profound, severe, significant |

| Intervention | accessibil*, AAC, adaptive, assisted, assistive, augment, braille, cochlear implants, habil*, inclusion, inclusiv*, sign language, special education, therap*, wheelchair |

| Population | children with, individuals with, people with, young adults with, underserved, marginalized |

| Disability Frameworks | social model, medical model, critical disability, disability studies, social role valorization, ecological model, complex embodiment |

Using these terms, the abstract column was searched using Excel’s “Find” function. Abstracts with one or more search terms were marked for screening and reviewed individually to determine topic relevance and central focus. Abstracts without a central focus on disability or disabled people were extracted from the set one at a time, and additional disability classifications were added as they emerged (after the initial search). Upon completion, 820 relevant works that were available online, in full text, and via Interlibrary Loan remained. Table 6 provides a summary of the screening process to filter out non-relevant references from the literature set.

Select a randomized sample from the literature

Given the high volume of articles identified and time limitations of the research team, a representative sample size from the literature set was calculated at 262 with a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of 5. In total, 282 references were randomly selected using an online randomizer tool.

Develop coding schema and establish intercoder reliability

The primary aim of the study was to gain a better sense of how disability is understood and represented in the LIS literature, and moreover, the extent to which critical disability has informed research and practice. To accomplish this goal, the reviewers established a coding schema to represent basic determinants of a critical disability approach. Table 7 provides a short list of codes and criteria. While precise definitions of critical disability theory differ, some we applied the following common criteria to rating the articles (Alper and Goggin, 2017; Goodley, 2013; Meekosha and Shuttleworth, 2009).

- Connects theory with practice/praxis and vice versa (Code: TAP). The article explicitly sits within ongoing conversations among academic research communities, communities of practice (e.g. librarianship, occupational medicine), and the disability communities being discussed. The criteria for connection between theory and practice/praxis refers to connections with ongoing discussions that affect the lived experiences of disabled people, as well as contributions to those discussions.

- Recognizes disability as socially and politically constructed (Code: CON). The article goes beyond an individual-medical definition of disability to include the understanding that disability is also a state of being (or an identity) produced through socially constructed definitions of physical, emotional, mental, and social “normalcy” and “fitness;” and reinforced through systems and infrastructure (e.g., information systems and physical structures) that support those understandings of normalcy.

- Acknowledges the corporeality of disability and engages with the reality of physical impairment and individual perception of limitations (Code: BOD). The article recognizes that, while disability is socially and politically constructed, it is also situated within the individual, and acknowledges experiences situated in the individual body and mind such as pain and sense of impairment.

- Explicitly acknowledges and/or addresses power and/or justice (Code: POW). The article explicitly acknowledges the existence of social and political power in information systems and services and/or frames equity/equality in terms of rights and justice. The writers of the article write from the position that disabled people have the right to equality and equity in information access. The article does not characterize access as optional, extra, or “charitable”.

- Builds on an activist historical tradition of fighting the exclusion of disabled people (Code: OPP). The article makes practical recommendations to improve access to systems, information, or data.

Each article was rated for each criterion on a scale from 1 (more true) to 5 (less true).

| Code | Criteria |

|---|---|

| TAP | Connects theory with praxis and vice versa. |

| CON | Recognizes disability as socially and/or politically constructed. |

| BOD | Acknowledges the corporeality of disability and engages with the reality of physical impairment and limitations. |

| POW | Explicitly acknowledges and/or examines issues related to power, access and justice. Frames access as a right. |

| OPP | Builds on activist historical tradition in response to exclusion of disabled people. Recommends changes to improve on oppressive or exclusionary systems. |

To ensure intercoder reliability, the three reviewers coded identical samples of twenty articles independently and compared finding using the ReCal 3 tool (Freelon, 2017; Freelon, 2010). Krippendorf’s alpha for the 3 coders was .867. Once intercoder reliability was established, each reviewer read and coded full text of their assigned set of articles.

| Coder | Sample Size |

|---|---|

| Coder 1 | 139 |

| Coder 2 | 118 |

| Coder 3 | 25 |

| Total | 282 |

Findings

The following findings begin with a general analysis of the identified 820 relevant references available online and in print, followed by a more nuanced analysis of a representative sample (n=282) of the relevant literature to better understand the ways in which disability has been understood and represented in the LIS research and practice literature over the years.

General overview of the disability-related literature published in LIS

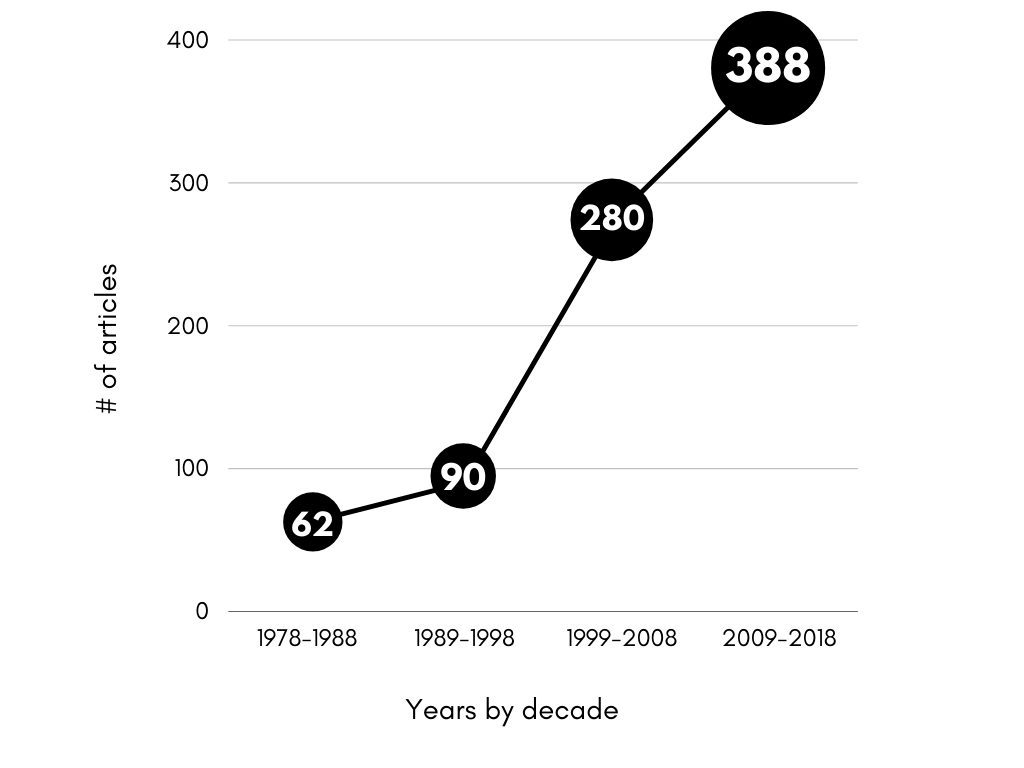

The number of LIS published articles focused on disability and disabled people has increased sharply over the past four decades. Figure 1 presents a distribution of disability-related articles published in LIS journals over the last four decades. As Hill noted, much of the work was practitioner focused, but the percentage of work focused on technology increased over time. Of the 820 relevant articles identified, 396 (48.29%) center on various types of technology or aspects of technology, including assistive technology, mobile technologies, web design, software development, communication devices, accessibility, and the digital divide over the 40-year span.

Figure 1: Distribution of articles published between 1978 and 2018

A focus on technology in original research.

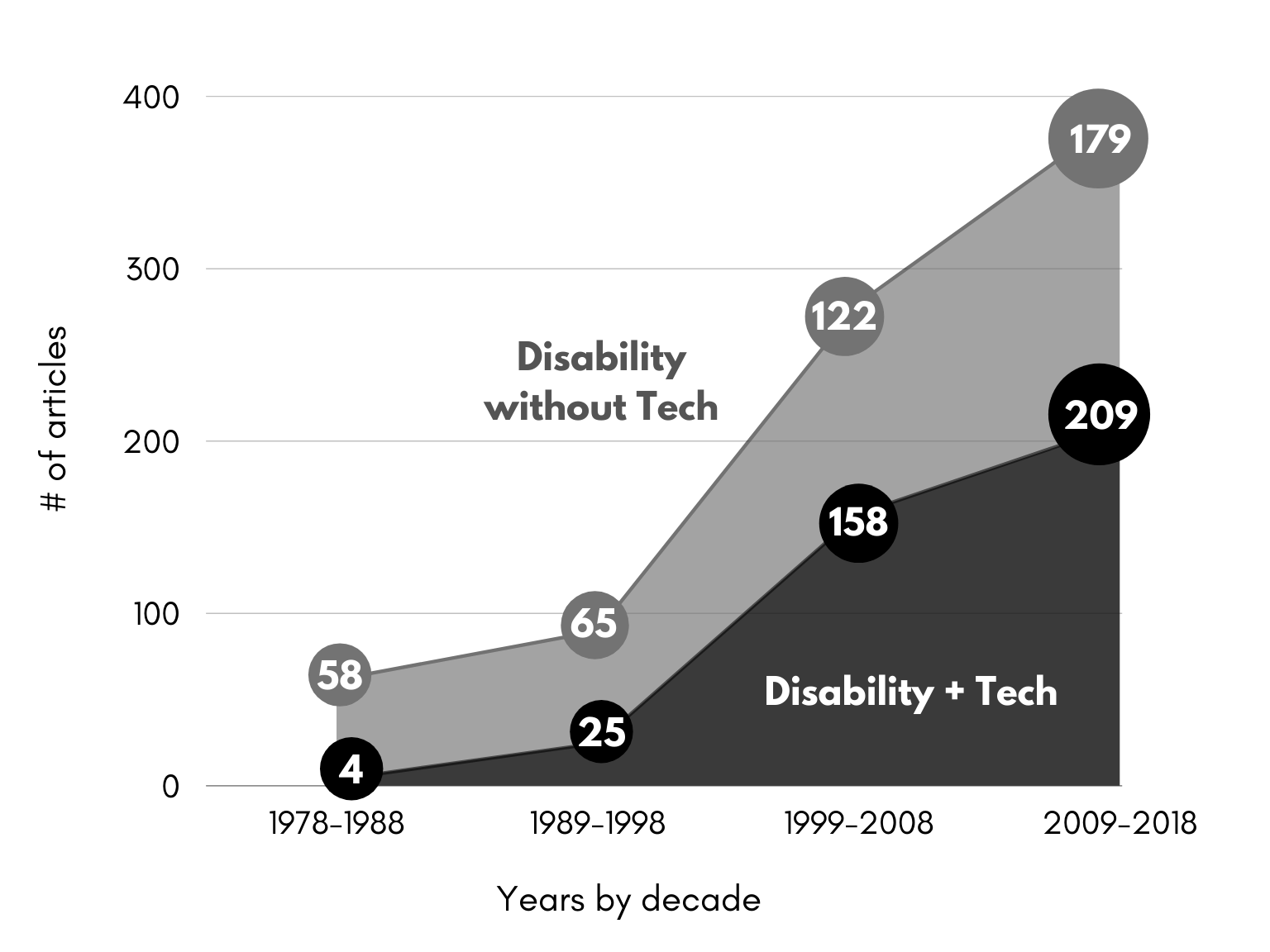

Figure 2 shows how many of the full final sample articles published in each decade were focused specifically on technology. Over the 40-year period, the percentage of papers focused on technology grew from 6.45% in 1978-1988 to 53.87% in 2009-2018.

Figure 2: Proportion of LIS disability articles focused on technology between 1978 and 2018

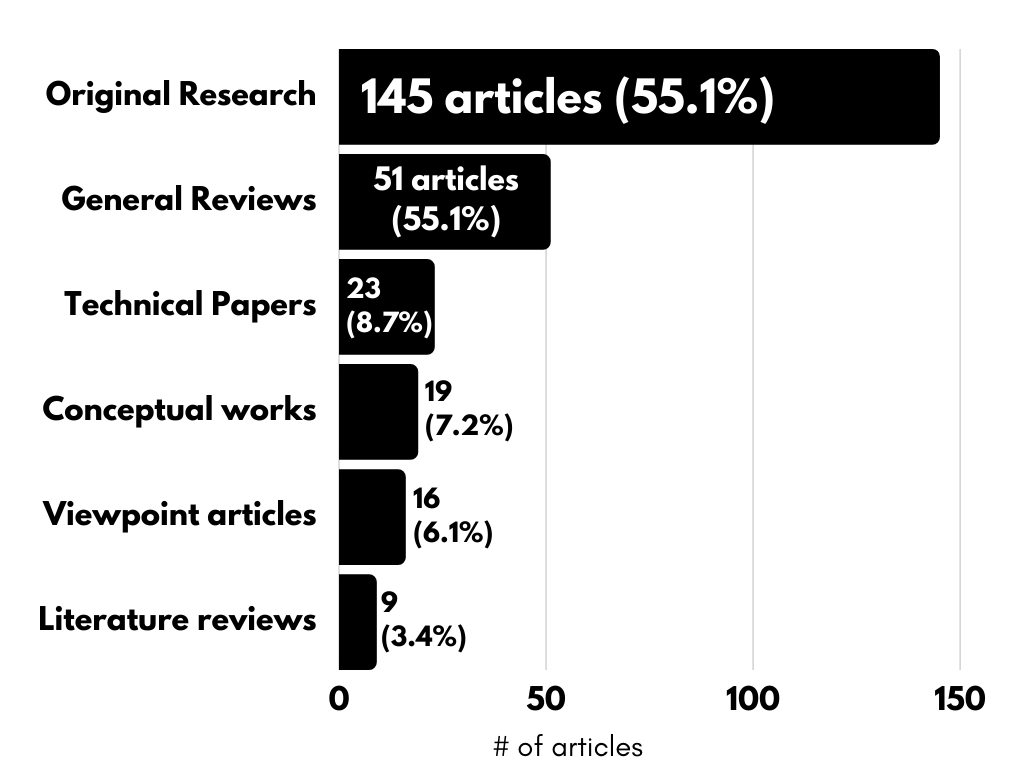

The final sample of 282 articles included original research, technical papers, conceptual works, viewpoint articles, and literature reviews. As highlighted in Figure 3, research papers comprised the largest portion of the literature set (55.1%). Of the 155 original research papers in the final sample, 124 (80.7%) studies predominantly focused on technology. Studies related to website accessibility comprised 44.8% of this research. Other technology-related topics included assistive technology design and evaluation, evaluation and assessment of mobile platforms, e-reader use and program implementations, online behavior, and distance education.

Figure 3: Distribution of articles in the representative sample

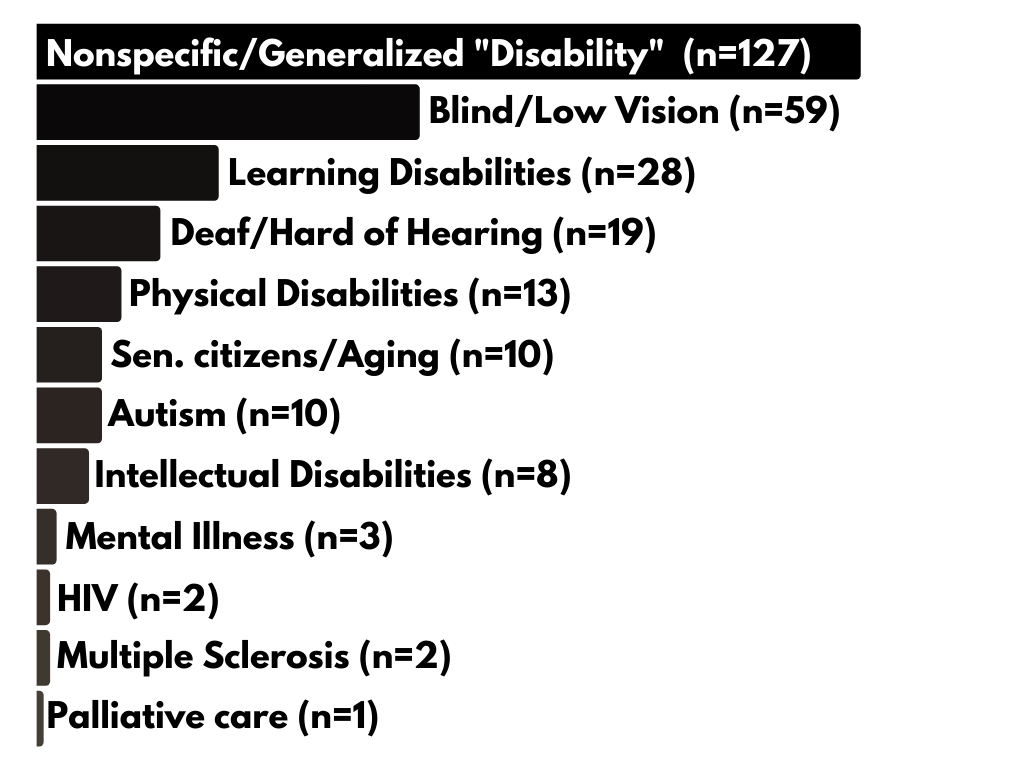

What disability communities do we study?

Figure 4 describes the frequency of specific disabilities identified in the representative sample. Most authors addressed disability as a single, broad category, generalizing among a wide range of conditions (41%, n=118). The second category of disability that emerged most frequently in the literature was blindness, vision impairment, and vision loss (19%, n=53), followed by learning disabilities (7.4%, n=21). These two findings echo Hill’s (2013) findings. The least frequently listed were palliative care patients (.3%, n=1), people with multiple sclerosis (.3%, n=1), and people with HIV (.7%, n=2). It should be noted that we did not add chronic illness categories to the initial search for disability topics. It is likely that the number of articles found is more reflective of LIS’ general exclusion of people with chronic illness from disability discourse over the period of study than a reflection of the total LIS research focused on HIV.

Figure 4:Categories of disability identified in the sample literature set

Assessing Disability Models

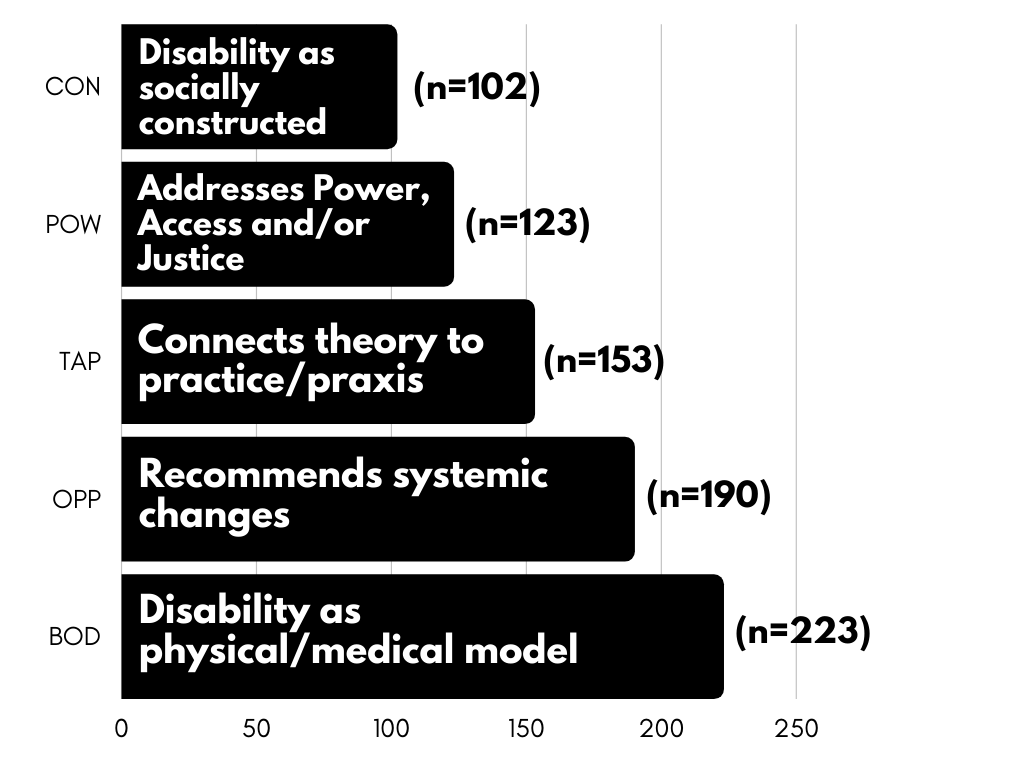

Articles were assessed and given a single point for each of the five critical framework criteria met (see Table 7 for explanation of criteria). This examination of the sample literature set reveals most works do not engage with critical disability frameworks (see Figure 5) in any meaningful way. Approximately 54% (n=153) of the articles explicitly connected the work to some form of theory or built on previous research and broader conversations in disability communities. Of the 282 articles, 79% (n=223) addressed disability as an individual physical and/or cognitive condition experienced by individuals. Only 36% acknowledged disability as a social and/or political construct. It should be noted that these categories (disability as physical and disability as social) are not mutually exclusive. Approximately one-third (32.7%) of the articles acknowledged disability influenced by a combination of both individual/physical and social/political factors. Approximately 44% (n=122) of the sample explicitly recognized information access and accessibility as explicitly related to power or as a justice issue. Sixty seven percent (n=190) of the articles in the sample recommended systemic change, but these changes varied based on authors’ specific definitions of disability. Those who defined disability primarily physically were more likely to suggest changes to technical systems. Those who defined it socially were more likely to suggest changes in services, policy, and training.

Figure 5: Frequency of Each Critical Criteria in Sample

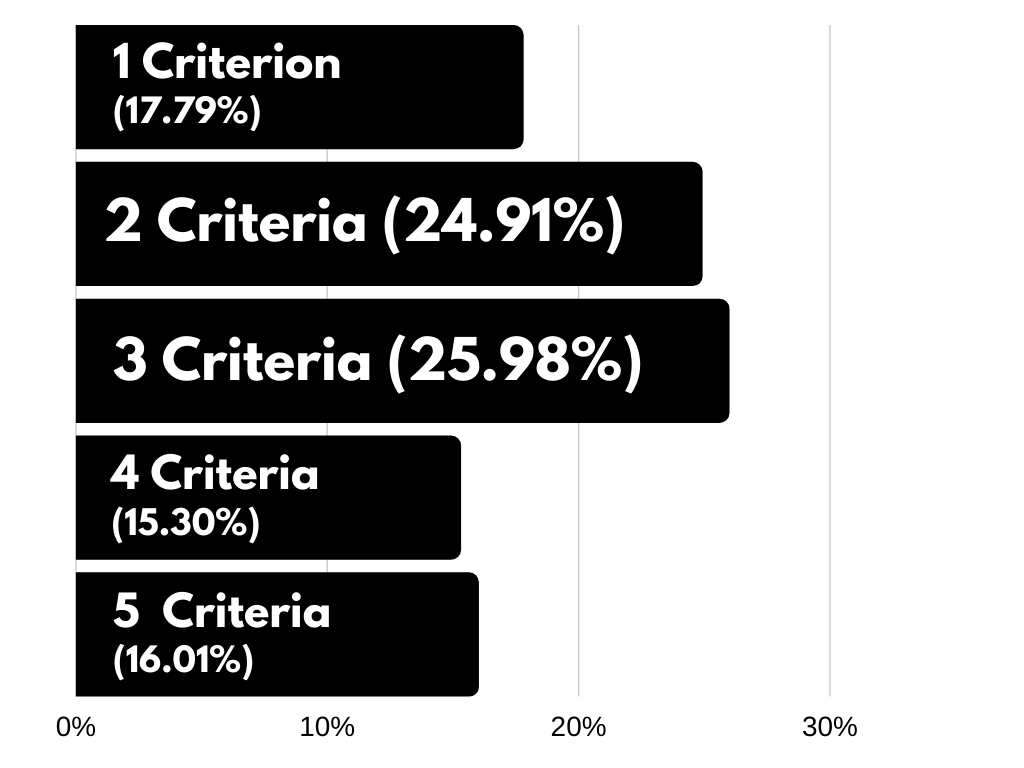

Critical criteria points were tallied and each article was given a critical framework score (CFS). The higher the CFS, the more criteria the title fulfilled. Of the articles in the sample, most fell between 2CFS (24.9%, n=70) and 3CFS (26%, n=73). Among the 2CFS group, BOD (recognizing disability as individual/physical impairment)(80%, n=56), and OPP (makes recommendations for change)(55.7%, n=39) were most frequently selected, suggesting that most articles took a strictly medical approach, and made suggestions for improvements based on that perspective. CON (disability as socially constructed) was the least popular (15.7%, n=11). Among the 3CFS group, BOD(83.6%, n=61), OPP (82.2%, n=60), and TAP (connects work to theory)(67.1%, n=39) were most frequently selected. POW (addresses power, access, and justice)(n=32) and CON(n=11) trailed behind. Among the 4CFS group, CON (60.5%, n=26) was selected least.

Figure 6: Percentage of Titles with Total Critical Framework Scores (CFS)

Many articles avoided discussing social implications of recommendations made beyond immediate service or technology improvements. Authors largely sidestepped intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and disability, focusing on a single-axis identity (disability only).

Hierarchies of Credibility

Assessment of credibility in articles coded as research studies were conducted qualitatively, as this data is more nuanced than other measures and therefore more difficult to evaluate quantitatively. Because many studies were multi-method, several studies fit into multiple categories. Five strong themes emerged in the sample studies that hint at a framework for assigning credibility and authority in the design and evaluation of LIS disability research (presented in order of relative frequency).

1. Self-referred authority: Author described systems/services/designs proposed, created, and (sometimes) evaluated by the author (without input from disabled people). These included self-generated system designs, and articles describing library programs.

2. Academic/Professional authority: Heuristic evaluations of existing programs and policies based on previous researchers’ and practitioners’ work, reflecting a traditional literature review model and traditional academic citation practices.

3. Academic/Institutional authority: Policy, practice, and curricular analyses – sometimes informed by previous researchers’ work and statements or input from local, national, and international disability organizations.

4. Self-referred authority/Mediated participation: Primarily experiments engaging disabled participants as research subjects in studies designed by (presumably nondisabled) researchers.

5. Experiential authority: Surveys and interviews that asked disabled people for their thoughts/opinions.

Discussion

LIS researchers continue to struggle with operationalizing the power and identity in studies related to access, racism, sexism, and ableism (Honma, 2005; Yu, 2006). Many also continue to ignore the social and technical implications of power relationships between and among groups. Kumbier and Starkey (2016) argue that the “conceptualization of access as a matter of equity requires library workers to account not only for the needs of individual users, or of specific groups of users but also for the contexts (social, cultural, historical, material, and economic) that shape our users’ terms of access.” The extent and quality of information services in support of disabled people directly reflects how disability is perceived and understood within the library and information science (LIS) literature, practice, and education. An appraisal of the LIS landscape suggests an unprioritized and short-sighted understanding of disability and much work to do.

We exist in a time where we are constantly confronted by the importance and value of human-centered and humane, respectful, compassionate information and data systems and services. Libraries are constantly innovating and reinventing themselves. The COVID-19 pandemic has, yet again, given us an opportunity to listen to our disabled and chronically ill colleagues and community members, reflect, and re-imagine a field that values and respects us all equally. What would it mean to decenter nondisabled perspectives in our practice and our research and to lean into the frameworks and values established in disability justice communities and literature? What would it mean to deconstruct our hierarchy of credibility and rely on disability communities to define who is disabled? What would our research and education look like if we regularly engaged with disabled people as research collaborators, rather than subjects?

In our current context, what could co-liberatory information work become? How would we expand our thinking and practice beyond technical accessibility, basic physical accessibility, and segregated programming models? Is this even possible, given the financial and administrative structures of most public and academic libraries? Much of the work sampled framed the discipline’s struggle to provide minimally equivalent access and services as innovation. A large percentage of technology research focused on basic web accessibility and relied on self-referred or professional authority. Few studies actually engaged disabled participants in ways that might influence the scope or design of the research. Fewer still considered intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1990), and the experiences of disabled BIPOC and/or disabled LGBTQIA+ people. This highlights the scarcity of training and education on disability issues, rights, justice, and accessibility in the field.

This gap has, in the past, limited continued development of substantive theory and praxis around disability and information within LIS. Reassessing our disciplinary and cultural preference for individualism over interdependence could support information systems, services, spaces, and communities built on care webs (Piepzna-Samarasinha, 2018) and institutional responsibility rather than individual access and responsibility, and wholeness (Berne et al., 2018) rather than clinical cure or rehabilitation. Recent growth in the number of researchers in this area, including BIPOC researchers (Cooke & Kitzie, 2021), disabled researchers (Brown & Sheidlower, 2019; Copeland et al., 2020; Niebauer, 2020; Schomberg and Hollich, 2019) and an increase in community-engaged and community-led research provides a point for optimism. This holds promise for more radical redesign of systems and services related to information, data, literacies, in more diverse communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has reminded us how important access to good health information is for public decision-making, but this need for public data and information is not new. The need for national and local level community information and data exists for marginalized folks all the time. We envision a public and academic (and perhaps health) librarianship that follows the lead of disabled community members, supporting decision-making and on issues of importance to them, such as personal data stewardship and safety, informed refusal, financial and insurance literacy. Community-led research and practice should move beyond leveling access and centering marginalized people to the work of dismantling margins whenever possible.

No Justice Without Critique

The critical disability framework we developed was not an especially rigorous one, in terms of building capacity for equitable and just information systems and spaces for people with disabilities, and most of the works examined only scored a 2 or 3 out of 5. Disability justice advocates have long pushed for much more transformative policies, disability-led work (rather than participatory work, which is typically led by nondisabled people), anti-capitalism, collectively oriented systems of care and access (rather than individually oriented access), humane and sustainable labor practices and ideologies, and collective liberation (Hosking, 2008; Berne et al., 2018). The framework also excluded explicit acknowledgment of intersectionality; justice-oriented methodologies (e.g. community-led research and autoethnographies). While a critical perspective alone isn’t enough to build just systems, we cannot hope to build just, humane, or useful systems with a timid stance on critique. Additionally, a myopic focus on individual behaviors, intentions and the cognitive perspective hampers our capacity for rigorous examination and improvement. A critical perspective enables us to contend with the social systems, norms, and frameworks that scaffold our research and practice, the definitions, assumptions, and biases that form their foundations, and the systems of power and control that serve as mortar to hold them together.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jessica Schomberg and Ryan Randall for your work in reviewing this paper. Your insightful feedback helped us clarify and strengthen our arguments and explanations. We would also like to thank Ian Beilin for managing this publication and keeping it on track through a summer of unrest and a year of pandemic life. This publication would not have been possible without your support.

This publication was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services RE-07-17-0048-17.

Accessible Equivalents

Figure 1 as a Table

| Year | Number of Disability-related articles |

|---|---|

| 1978-1988 | 62 |

| 1989-1998 | 90 |

| 1999-2008 | 280 |

| 2009-2018 | 388 |

Figure 2 as a Table

| Year | Disability with Tech | Disability without tech | Total articles | Percentage with Focus on Technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978-1988 | 4 | 58 | 62 | 6.45% |

| 1989-1998 | 25 | 65 | 90 | 27.78% |

| 1999-2008 | 158 | 122 | 280 | 56.43% |

| 2009-2018 | 209 | 179 | 388 | 53.87% |

Figure 3 as a Table

| Number of Articles | Percentage of Articles | |

|---|---|---|

| Original research | 145 | 55.13% |

| General reviews | 51 | 19.39% |

| Technical papers | 23 | 8.75% |

| Conceptual works | 19 | 7.22% |

| Viewpoint articles | 16 | 6.08% |

| Literature reviews | 9 | 3.42% |

Figure 4 as a Table

| Category of Disability | Number of Articles | Percentage of Articles (Rounded) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-specific and generalized | 127 | 45 |

| Blindness and low vision | 59 | 21 |

| Learning disabilities, including dyslexia and other print disabilities | 28 | 10 |

| Deafness and hearing impairment | 19 | 7 |

| Physical disabilities | 13 | 5 |

| Autism | 10 | 4 |

| General aging | 10 | 4 |

| Intellectual disabilities, including Down syndrome | 8 | 3 |

| Mental illness, including dementia | 3 | 1 |

| HIV | 2 | 1 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 2 | 1 |

| Palliative – end of life | 1 | 0 |

| Totals | 282 | 102 |

Figure 5 as a Table

| Critical Criteria | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| CON (Disability as socially constructed) | 102 |

| POW (Addresses power, access, and/or justice) | 123 |

| TAP (Connects theory to practice/praxis) | 153 |

| OPP (Recommends systemic changes) | 190 |

| BOD (Disability as physical/medical model) | 223 |

Figure 6 as a Table

| Number of Criteria Fulfilled | Percentage of Articles | Number of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Criterion | 17.79% | 50 |

| 2 Criteria | 24.91% | 70 |

| 3 Criteria | 25.98% | 73 |

| 4 Criteria | 15.3% | 43 |

| 5 Criteria | 16.01% | 45 |

References

Alper, M., Goggin, G. (2017). Digital technology and rights in the lives of children with disabilities. New Media & Society 19, 726–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816686323

American Library Association. (2009, February 2). Services to People with Disabilities: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights. Advocacy, Legislation & Issues. http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/librarybill/interpretations/servicespeopledisabilities

American Library Association. (2015). “Standards for Accreditation of Master’s Programs in Library and Information Studies. http://www.ala.org/accreditedprograms/standards/glossary.

American Library Association. (2019). “Democracy Statement | About ALA.” http://www.ala.org/aboutala/governance/officers/past/kranich/demo/statement.

Barnartt, S., and B. M. Altman. (2001). “Exploring Theories and Expanding Methodologies: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Title.” Research In Social Science and Disability.

Becker, Howard S. (1966). “Whose Side Are We On.” Social Problems 14. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/socprob14&id=245&div=36&collection=journals.

Berne, P., Morales, A. L., Langstaff, D., & Invalid, S. (2018). Ten principles of disability justice. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 46(1), 227-230.

Bourg, C. (2014, January 16). The Neoliberal Library: Resistance is not futile. Feral Librarian. https://chrisbourg.wordpress.com/2014/01/16/the-neoliberal-library-resistance-is-not-futile/

Braddock, D. & Parish, S. (2001). An institutional history of disability. In G. L. Albrecht, K. Seelman & M. Bury Handbook of disability studies (pp. 11-68). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781412976251.

Brown, R., & Sheidlower, S. (2019). Claiming Our Space: A Quantitative and Qualitative Picture of Disabled Librarians. Library Trends 67(3), 471-486. doi:10.1353/lib.2019.0007.

Cooke, N. A., & Kitzie, V. L. (2021). Outsiders-within-Library and Information Science: Reprioritizing the marginalized in critical sociocultural work. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24449

Copeland, C. A., Cross, B., & Thompson, K. (2020). Universal Design Creates Equity and Inclusion: Moving from Theory to Practice. South Carolina Libraries, 4(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.51221/sc.scl.2020.4.1.7

Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241.

Ettarh, F. (2018). Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves. In The Library With the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2018/vocational-awe/

Fadyl, J. K., Teachman, G., & Hamdani, Y. (2020). Problematizing ‘productive citizenship’ within rehabilitation services: Insights from three studies. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(20), 2959–2966. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1573935

Freelon, D. (2017). ReCal3. Retrieved from http://dfreelon.org/recal/recal3.php

Freelon, D. (2010). ReCal: Intercoder reliability calculation as a web service. International Journal of Internet Science, 5(1), 20-33.

Gibson, A. N., & Hanson-Baldauf, D. (2019). Beyond Sensory Story Time: An Intersectional Analysis of Information Seeking Among Parents of Autistic Individuals. Library Trends, 67(3), 550–575. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2019.0002

Goodley, D. (2013). Dis/entangling critical disability studies. Disability & Society, 28(5), 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.717884

Goodman, N., Morris, M., Boston, K.(2019). Financial Inequality: Disability, Race, and Poverty in America. A report by the National Disability Institute. Retrieved from https://www.nationaldisabilityinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/disability-race-poverty-in-america.pdf

Harris, C. I. (1993). Whiteness as Property. Harvard Law Review, 106(8), 1707–1791. https://harvardlawreview.org/1993/06/whiteness-as-property/

Hill, H. (2013). Disability and accessibility in the library and information science literature: A content analysis. Library & Information Science Research, 35(2), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.11.002

Honma, T. (2005). Trippin’ Over the Color Line: The Invisibility of Race in Library and Information Studies. InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies, 1(2). http://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj0w1mp

Hosking, D. L. (2008, September). Critical disability theory. In A paper presented at the 4th Biennial Disability Studies Conference at Lancaster University, UK.

Jaeger, P. T., Gorham, U., Bertot, J. C., & Sarin, L. C. (2014). Public Libraries, Public Policies, and Political Processes: Serving and Transforming Communities in Times of Economic and Political Constraint. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Knox, E.J.M. (2020). Intellectual freedom and social justice: Tensions between core values in librarianship. Open Information Sciences, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/opis-2020-0001

Kumbier, A., & Starkey, J. (2016). Access Is Not Problem Solving: Disability Justice and Libraries. Library Trends, 64(3), 468–491. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2016.0004

Lee, J., & Cifor, M. (2019). Evidences, implications, and critical interrogations of neoliberalism in information studies. Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, 2(1), 1–10. https://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/122

Mathios, K. (2019, July 31). The commodification of the library patron. EdLab, Teachers College Columbia University. https://edlab.tc.columbia.edu/b/23060

Meekosha, H., & Shuttleworth, R. (2009). What’s so ‘critical’ about critical disability studies? Australian Journal of Human Rights, 15(1), 47–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1323238X.2009.11910861

Niebauer, A. (2020, February 28). Information studies prof works to address mental illness among librarians. UWM REPORT. https://uwm.edu/news/information-studies-prof-works-to-address-mental-illness-among-librarians/

Oliver, M. (1990). The Ideological Construction of Disability. In M. Oliver (Ed.), The Politics of Disablement (pp. 43–59). Macmillan Education UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20895-1_4

Olkin, R. (1999). The personal, professional and political when clients have disabilities. Women & Therapy, 22(2), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015v22n02_07

Pionke, J. J. (2017). Toward Holistic Accessibility: Narratives from Functionally Diverse Patrons. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 57(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.57.1.6442

Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Arsenal Pulp Press.

Schomberg, J., and Hollich, S. (Eds.). (2019). Disabled Adults in Libraries [Special issue]. Library Trends, 67(3). https://muse.jhu.edu/issue/40307

Sparke, M. (2017). Austerity and the embodiment of neoliberalism as ill-health: Towards a theory of biological sub-citizenship. Social Science & Medicine, 187, 287–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.027

Stikkers, K. (2014). “ . . . But I’m not racist”: Toward a pragmatic conception of “racism.” The Pluralist, 9(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5406/pluralist.9.3.0001

Webb, C. J. R., & Bywaters, P. (2018). Austerity, rationing and inequity: Trends in children’s and young peoples’ services expenditure in England between 2010 and 2015. Local Government Studies, 44(3), 391–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1430028

Xu, J., Kang, Q., & Song, Z. (2015). The current state of systematic reviews in library and information studies. Library & Information Science Research, 37(4), 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2015.11.003

Yu, L. (2006). Understanding information inequality: Making sense of the literature of the information and digital divides. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 38, 229–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000606070600