Library Lockdown: An escape room by kids for the community

In Brief

Hoping to bring the unexpected to Nebraska City, the Morton-James Public Library applied for an ALA Association for Library Service to Children Curiosity Creates grant to undertake an ambitious project: build an escape room. In a library storage room. With children. The hope was by trying something completely different, we could increase interest in the library throughout the community and build a sense of ownership in the participants, while encouraging creativity and having a lot of fun. Library Lockdown was a four-month program that brought several dozen kids together—age 8 to 13—to build a fully-functioning escape room. Their creation, the Lab of Dr. Morton McBrains, is now open for business.

Introduction

It all began with a “what if?” and a “why not?” Well, really it started with a large storage room and a grant solicitation. The result was a transformation of not only a space in the library, but in the library’s space in the community. In the spring of 2016, we guided a group of kids in building an escape room in the Morton-James Public Library. It was an extraordinarily fun (and time consuming!) project; and while our goals were mainly focused on what the participants and what the community would take away from it, we were the ones who probably learned the most.

We shared some of our reflections in a short Library Journal article (Thoegersen & Thoegersen, 2016), but wanted to share our experiences in more depth. Our hope is that, after reading this, you will be inspired to create your own flavor of Library Lockdown in your own library. But first, a little exposition.

The Place

Aerial View of Morton-James Public Library, Morton-James Public Library (CC-BY 4.0)

Morton-James Public Library serves the community of Nebraska City, in southeast Nebraska. Nebraska City has a population of 7,289 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). The population is predominately white (91.5%) and is 10.9% Hispanic/Latino. The percentage of people with income below the poverty level was 15.1%, which is higher than the percentage for the state of Nebraska (12.9%), but comparable to the United States as a whole (15.6%).

Built in 1897 (with additions in 1933 and 2002), the public library building is beautiful and historic; it’s listed on the National Register of Historic Places (Nebraska State Historical Society, 2012). It can also seem a bit of a maze and has lots of nooks and crannies. One such nook was a rather large storage room full of used books, holiday decorations, and a miscellany of craft supplies. This room also had some water damage and moldy carpet that needed to be replaced. It was clearly in need of some love and perhaps a new purpose, as well.

The Project

In August 2015, we became aware of the Curiosity Creates grants administered by the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) division of the American Library Association (ALA). Thanks to a donation from Disney, over seventy $7,500 grants were to be awarded to libraries in order “to promote exploration and discovery for children ages 6 to 14” through programming that promotes creativity (American Library Association, 2015). The grant could be used to grow an existing library program or to develop completely new programming. Grant recipients were notified in October 2015, and they were expected to implement their project and complete a project report by May 31, 2016.

Inspired by the availability and purpose of this grant, the recent popularity of escape rooms around the world, and the breakoutEDU movement, Rasmus hit upon an intriguing idea: What if we turned this neglected storage room into an escape room? And why not give kids a chance to build it themselves?

Interlude: So, what is an escape room?

The escape room concept was created by 35-year-old Takao Kato in Kyoto, Japan in 2007 as a way to have a real-life adventure like those he encountered in literature as a child (Corkill, 2009). Escape rooms are like a real-life video game, where you and your friends are “locked”* ((not really, since the fire marshal would not approve)) in a room and must search for clues and solve puzzles to determine how to get out. “In order to escape the room the player must be observant of his/her surroundings and use their critical thinking skills as well as elements in the room to aid in their escape” (The Escape Game Nashville, 2015). Escape rooms come in many shapes and sizes but generally include the following:

- A story

- Puzzles, clues, and riddles

- A time limit

- A lot of fun

Library Lockdown

Thus the idea of Library Lockdown was born. The plan was for the program to run during the spring of 2016. The group of kids would meet at the library weekly, first learning about escape rooms and puzzles, and then creating the story, decorations, and puzzles for one of their own. After being awarded the ALSC grant in October 2015, library staff went to work clearing out the storage room. The carpet was replaced with the help of a separate, local grant. Library Lockdown was advertised in person by circulation staff, in the local paper, and in local schools. Potential participants were asked to fill out a registration form and a photo waiver.

Based on the registration forms received, Saturdays were selected as the weekly meeting time. The first meeting was February 13th, and two dozen kids showed up. We had meetings every Saturday until the grand opening on May 25th. ((Except for Arbor Day weekend, that is. Nebraska City is “home of Arbor Day”, and most of the kids were participating in the annual Arbor Day Parade.))

The number of kids attending each meeting varied from ten to nearly 30; with usually around fifteen present. Nearly three dozen kids participated in at least one meeting, but there was a core group of about ten that attended the majority of the meetings. This provided continuity from week to week.

The format for the meetings was generally five to ten minutes of introducing the day’s activities and forty-five to sixty minutes of work, followed by lunch (paid by the grant). The first few weeks were focused on having the kids solve puzzles on a theme (appropriately, the first week’s theme was Valentine’s Day).

During week three, the kids selected the theme for the room (zombies), and also decided they wanted to make a zombie movie that would play before and during an escape room run. Then, they began making puzzles themselves and creating different parts of the room. For every subsequent week (except the week we filmed the movie), we planned for at least four separate groups, each supervised by an adult. These groups initially started out very broad:

- The tech group was provided with old electronics, a laptop, a couple of Makey Makey kits and a Squishy Circuits kit to use as the basis of a puzzle.

- The storytellers brainstormed about the backstory for the room, as well as the screenplay for the zombie movie.

- The puzzle group was tasked with coming up with ideas for puzzles.

- The “zombiemakers” were given costume makeup and old clothes to practice zombie makeup and create zombie clothes for the movie.

As the weeks progressed, group work became far more specific; they would have a specific task related to a specific piece of the room, e.g. a particular puzzle or props for the room.The final meetings involved pulling everything together and setting up and testing the room.

Creating decorations for the Lab of Dr. Morton McBrains; Morton-James Public Library (CC-BY 4.0)

The grand opening event was on Wednesday, May 25th. The families of all of the participants were invited, along with members of the community. The Nebraska City Tourism and Commerce organization held a ribbon cutting, which was covered by the local paper and radio station (Partsch, 2016; Hannah & Swanson, 2016). The city’s mayor and his family were the official first group to attempt to escape the room, and, while they were “locked” in solving puzzles, everyone else was in the library gallery having a pizza party and solving puzzle boxes that were on their tables. Over 100 people attended the grand opening event, including twenty-two of the Library Lockdown participants. Every participant received their own lock and a family pass to the commercial escape room, Escape This, which opened in Nebraska City just as Library Lockdown wrapped up.

The Library Lockdown escape room is now open for business and is free for anyone to play, though donations are accepted. Groups must book the room in advance by calling the library. The room can be booked any day the library is open from thirty minutes after opening to an hour and a half before close. Generally, only one group may play the room per day, ensuring that there is time to reset the room for the next group and that it isn’t taking up too much staff time. Since its opening, twenty-five groups have played the room (over 150 individuals), and there are currently eight reservations through December 2016. The groups have been families, work groups, school classes, scouting troops, and groups of friends. The escape room will likely remain open until there is a new, interesting idea for how to repurpose the room once again.

Fostering creativity

“Although creativity is a complex and multifaceted construct, for which there is no agreed-upon definition, it is viewed as a critical process involved in the generation of new ideas, the solution of problems, or the self-actualization of individuals…” (Esquivel, 1995, p. 186)

When we discussed what we wanted kids to take away from their participation in Library Lockdown, we relied heavily on a white paper by Hadani & Jaeger (2015) highlighted by ALSC and published by the Center for Childhood Creativity. This paper introduces seven components of creativity:Imagination & Originality, Flexibility, Decision Making, Communication & Self-Expression, Motivation, Collaboration, and Action & Movement. For each component, the authors present a body of research explaining its role in fostering creativity and provide strategies and examples for incorporating each component into projects.

As part of the grant application, we were asked to identify which of the seven components were most critical for the project. We chose to focus on two: Imagination & Originality, and Collaboration. While all of the components played a role in the project, we felt these two were the most vital to success and used the strategies suggested by Hadani & Jaeger for these components as a guide when planning Library Lockdown meetings.

Imagination was key because the kids were starting with an empty room and no story. They had to consider many possibilities and visualize the details of the escape room. Hadani & Jaeger provided five strategies for promoting imagination, which we found to be some of the most valuable guidance, especially during the early weeks of the project.

- Generate ideas by building on other ideas: This was how we approached puzzle making in the beginning. We created dozens of puzzles for the kids to try out (some thought up by ourselves, many modified from those found through amazing resources like breakoutEDU). We would then ask the kids to build a similar, but new, puzzle. This didn’t always lead to the creation of functional puzzles, but it did help put kids in the mindset of creating their own puzzles.

- Generate lots of ideas: We used this strategy for determining the theme and story for the room. At the third session, after spending a few weeks having the kids solve and modify puzzles, we had the kids pick a theme for the room. They split into groups and, guided by an adult, wrote down as many possible themes as they could think of. They came up with some pretty awesome themes–like candyland, haunted library, and star wars–before selecting “zombie” by voting for their favorites.

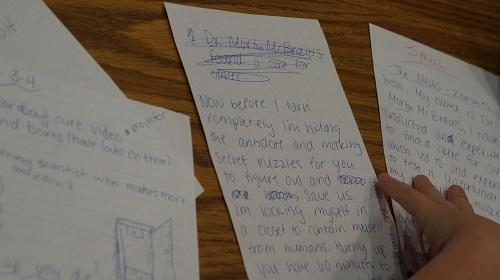

Drafts of the story for the Library Lockdown escape room; Morton-James Public Library (CC-BY 4.0)

- Plenty of imaginary play and unstructured time: Though we often provided very structured tasks for the kids to work on during meetings, we also included several opportunities for freer, less structured activities. This included giving groups a room full of craft and other materials and puzzle books, and letting them spend the entire time attempting to make puzzles. This time did not result in many strong, functional puzzles, but allowed the kids to experiment and play.

Library Lockdown participants working together to create a puzzle with Play-Dough; Morton-James Public Library (CC-BY 4.0)

- Encourage new ideas and building on others’ ideas: We generally had kids work in groups of three to six, each led by an adult, which allowed us to guide conversations and ensure each kid was able to share their ideas in a positive environment.

Given the time constraints and the variety of tasks involved, the kids had to collaborate and rely on each other to ensure that the puzzles, props, and story formed a cohesive whole. One of Hadani and Jaeger’s suggested strategies for promoting collaboration was providing “project-based opportunities that are structured to avoid merely splitting of tasks in favor of sharing and co-creating.” Given the number of participants and the amount and variety of work that needed to be accomplished, logistically, we had to split participants into multiple groups, each with a different purpose or task. However, each group had to work together to achieve their individual objectives, and all of the groups fed into the same shared goal.

A good example was a puzzle that involved a robot maze. Using grant money, we purchased Dash and Dot, a set of programmable robots. The group working on the puzzle first worked together to program the robots so that by pushing buttons on Dot, Dash would move. At subsequent meetings, they determined how wide the maze paths had to be for Dash to be able to move easily, designed several iterations of the maze on paper, measured out and colored in where the walls would be, and painted the maze. At every step, they worked on these tasks together. Sometimes this was out of necessity (it’s pretty hard to use a chalk line alone), but mostly they were doing tasks together that they could have done individually. This allowed them to problem solve, share ideas, and create something better together.

Psychological ownership

A major outcome we were interested in fostering was a sense of ownership of the library among the community, especially the youth participating in Library Lockdown. Pierce et al. (2003) define psychological ownership as “that state where an individual feels as though the target of ownership or a piece of that target is ‘theirs’ (i.e., it is MINE!)” The project was embarked upon with the hope that creating a physical space would instill a sense of accomplishment and pride, and the children would develop a sense of ownership over the library. Though we did not attempt to measure the participants’ feelings of ownership in any formal way, many of the participants started referring to the escape room as “their room,” and those who played the room with their family or school groups pointed out the puzzles they helped make and enjoyed watching their teammates attempt to solve them. From being on a first name basis with the library director, to having access to a room off limits to everyone else, to keeping secrets about the project from family and friends (can’t give away clues or answers to the puzzles!), we noticed participants definitely had an increased level of comfort in the library space and were clearly very proud of what they had accomplished.

Engaging the community

Working with groups and individuals in the community proved to be both easy and rewarding. From planning to opening, we sought to involve a variety of groups in the project. Initially, we approached principals and teachers at local schools to advertise and help recruit students to participate. This also led to a few teachers volunteering to help.

When the group decided to make a zombie movie, we approached an acquaintance at the local radio station, who volunteered to direct, film, and edit the movie for free. The city police chief also agreed to be interviewed about the zombie invasion. The city mayor and his family readily agreed to be the first official group to try out the escape room. This drummed up publicity and provided a final, grand opening event for the group to celebrate their accomplishment. Though no one declined the invitation to participate, we had a couple of people who offered to help, but had to back out for various personal reasons.

Nebraska City Chief of Police being interviewed about the Zombie Apocalypse; Morton-James Public Library (CC-BY 4.0)

Gameplay and game mechanics

The entire project was a clear case of ‘process’ over ‘product’. As we explained above, our main goals involved engaging the kids and inspiring them to be creative. Having an escape room was the secondary goal, and, in order to ensure that the room worked well as an experience for the community, we had to make sure the gameplay was there. Whether you enjoy a game or not, is closely related the flow of the experience (Sweetser & Wyeth, 2005).

Gameplay hinges on both variety and functioning mechanics. Variety means that you aren’t simply solving riffs on the same word-replacement puzzle. Functioning mechanics is that the puzzle can be solved, but more importantly it relates to balance.

When explaining the importance of a balanced experience to the kids, we kept coming back to the video-game metaphor. Imagine a race game. If the track you are racing on is a straight line, he best car always wins and no skill is required. On the other end of the spectrum the track can curve so much and beat even the most skilled driver. Neither of those experiences will be a lot of fun. The first one will be boring and the second one frustrating.

We ran a puzzle in which they had to find a key to a lock. Then we tasked them with creating a similar experience for another group. The first thing we heard was a gleeful ‘they will never find it’. Then you remind them of the video game and the racetrack. We want them to find the key. Impossible isn’t fun.

Structuring creativity

Going into the project, we had intended to give a lot of freedom to the participants. We would create the framework and ensure that the project was progressing according to the timeline, but creative choices would be made by the children. The stories and the puzzles would be their own. However, as the project progressed, we realized we needed to put some limits on where they could express their creativity. Too much freedom resulted in several problems, including paralysis (uncertainty of how to proceed),unfeasible or impractical ideas, and a disregard for time constraints. We realized that, given our short timeframe and the logistics involved, we would need to create a bit more structure around the creativity.

There were two main ways we approached this. The first was what we were already trying to do: give them a wide breadth for creativity, then funnel their ideas into a realistic plan. But this creative brainstorming was more effective for items like story and decorations, less so for puzzle making. We allowed the kids to express wild ideas, and then we took these ideas and adapted them into a realistic plan that we could implement. For example, once a zombie theme had been selected, many kids expressed a strong desire to actually dress up as zombies. Of course, this wouldn’t make a whole lot of sense as part of an escape room that would be open for months. Instead, we made the zombie movie to provide the backstory and ambience for the room and give the kids their chance to zombies for a day.

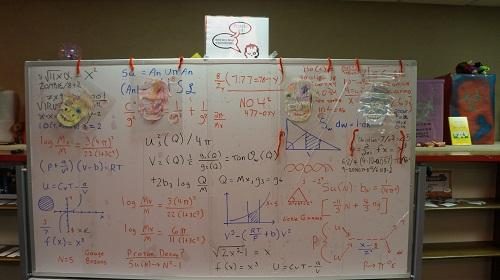

The second approach become essential in the last weeks of the project: providing a realistic frame that had a creative component. We would present the basics of a puzzle and have specific ways that they could make decisions, be creative and contribute. One puzzle involved mathematical equations on a whiteboard and several zombie head cutouts. We explained the puzzle to the kids. They colored and laminated the zombie heads (the laminator was definitely a favorite!). Using examples from math books, they helped fill the white board with equations. They had a blast doing this (and slipping their names in there, too).

“Beauty is in the eye of the zombie-holder”, one of the puzzles created as part of Library Lockdown; Morton-James Public Library (CC-BY 4.0)

Our kids responded to having a clear goal in mind that was smaller and more manageable than the room as a whole, but still allowed them to play and infuse their ideas into the project.

Building repeatability, building modularity

As we worked on the project, we thought about its adaptability. How could this concept translate into a variety of contexts, especially considering most libraries would not have $7,500 to spend on similar projects or such a large space and/or staff time to devote to it? In addition, we grew concerned about how best to tie the room and the various puzzles together, as well as how we might make the room enjoyable for a variety of skill levels. We were also conscientious of the time it might take to reset the room and ensure that it was reset correctly.

The solution for all of these concerns was simple: modularity. When initially considering the escape room, we imagined the puzzles would be linear and tie into each other. Imagine, you find a key early on and it does seemingly nothing. Your team struggles on, finds more clues and solves more puzzles until the very end, when someone remembers that key from the beginning, and it all makes sense.

While the temptation to tie every puzzle into a sequence and the bigger narrative certainly was compelling, we learned that a clear division between individual puzzles makes sense for project like this. The end result was ten puzzles separated conceptually, as well as physically. Each puzzle corresponded with a locked box. Each box contained a code to be typed into a computer terminal. Once any eight of the codes had been entered, the terminal provided the code to the safe (which, of course, held the antidote to the zombie apocalypse). Ambitious/completionist players could attempt to solve the final two puzzles for bragging rights if they still had time remaining.

This approach provided benefits both during the creation of the escape room and after it opened as well:

- Having distinct puzzles simplified the planning process, which was a boon given our time constraints and the age of the kids working on the room (most of whom were nine or ten).

- Since all of the puzzles are self-contained, it is very easy for staff to quickly check if each puzzle is ready to go when resetting the room for a new group.

- We are able to raise and lower the difficulty of the room by changing the number of solved puzzles required to win, by changing a number in the computer program where players enter the codes.

- We can remix the gameplay to accommodate groups of different sizes and skill levels. Recently, the local middle school asked to bring their students totry the room. The groups had about a dozen students and only thirty minutes. We had them ignore the overall goal of the room, divided them into smaller teams, and instructed them to work on one puzzle at a time. Once they solved a puzzle, we helped them to reset it, so another group could attempt it, and they moved on to another puzzle.

- Other libraries can use the same basic format and modify it to fit their time, budgetary, and space limitations.

Feedback

Participants that attended the grand opening event (22 of the 35 total participants) were asked to complete a short survey about their experience in Library Lockdown. They were asked three Likert-scale questions (“How much fun did you have?”, “Would you do it again?”, “Is the library fun?”) to which they provided generally positive responses (average of 4.5, 4.5, and 4.3, respectively). They were also asked what they liked best about Library Lockdown. Three of the answers were very broad (“the whole thing”, “everything”, “building it”); eight answers mentioned making or solving puzzles; and nine mentioned unique, specific items:

- Computers

- Working with locks

- The story making

- Watching movie

- The mayor trying to get out

- Build lego sets

- The people

- Making play-dough shapes

- eating

Our interpretation of these responses is that the group really enjoyed the puzzle-based structure of Library Lockdown, but many of the kids responded to vastly different aspects of project.

We also did informal interviews with parents during and after the project and got some very positive feedback from them on both the project and the final result. In addition, the program was effective overall for creating hype/awareness of library and reminding our community that we are still very much around. The head of the local radio/television station mentioned how the library seemed to have changed recently, stating “You guys are doing all this stuff now.” Most of the library’s programming outside of Library Lockdown during the preceding months was not new at all, but having a flagship event like this seems to have raised our visibility in our community.

Final thoughts

This was a gratifying project, and we really enjoyed working on it. We also learned a great deal along the way. It was a massive time commitment. The group met for ninety minutes every Saturday from February until May. We also spent a combined ten to fifteen hours per week planning, preparing, and cleaning up. Enthusiasm for the project, for kids, and for puzzles was a requirement. Anywhere from ten to almost thirty kids would attend each session. This made planning and logistics a challenge: How much space and food do we need? How many volunteers or staff members need to be present? How many activities do we need to have ready? During the later weeks, how are we going to bring this all together?!

By the final weeks, we got very good at being prepared. We had structured activities and backup plans. We also ensured we had enough staff and volunteers to have a high staff to kid ratio (1:4), which allowed us to be more flexible when something different happened than expected (or if more kids showed up than expected).

We wanted this project to bring in a diverse group of kids, and in many ways, it did. There was a near 50-50 split of boys and girls, and, though Nebraska City is predominantly white, multiple cultural backgrounds were represented in our group. There were a few areas we wish we had been more successful in.Though we advertised outside the library in hopes of attracting non-library users, we had few participants who weren’t already library users. We also advertised directly to the Hispanic and home school populations in our city. Though several returned the registration forms, none ultimately attended any of the sessions. In future projects, we will attempt to communicate more closely with potential participants in these groups to better understand what kept them from attending.

Though not a major issue for us, it was important to consider any laws that may be applicable to the room itself. We asked the local fire marshal to review the room for any potential issues, and he approved of the use, as long as the door remained unlocked and unobstructed. The Library Lockdown room is wheelchair accessible and navigable. All of the puzzles can be solved by someone with physical limitations or who is deaf or hard of hearing with little or no assistance. The instructions for the room are written and are also spoken aloud. In addition, reservations are scheduled to allow for a staff person to be present in the room and provide assistance as needed.

We were aware that not every puzzle would work out, so we chose to err on the side of having too many. That way, if something broke – which happened – a back-up puzzle was ready to go. We ended up having ten puzzles in the final room.

You will want to do some beta-testing before having the general public go through the room. We first invited some of our volunteers who had not been involved in the project to try it. This gave us a sense of what worked and what didn’t work. It also instilled some confidence in the project as a whole, as they all seemed to thoroughly enjoy themselves.

We built the room with the intention of not having an employee/volunteer staffing it. But we found that having someone along to guide the participants and explain the rules made a difference. Hints are totally ok. Good-natured teasing as well. The typical group will make it out of the room with 5-10 minutes left on the clock, which is ideal.

Though we were lucky enough to receive a generous award, which allowed us to purchase many materials for Library Lockdown, we certainly could have undertaken a similar project on a smaller budget. We took advantage of the resources on breakoutEDU, used easily accessible craft supplies, repurposed items that were already at the library (including various things hiding in the storage room before it was cleaned out), and received donations of food from local restaurants. These are strategies that other libraries can take advantage of if interested in building an escape room of their own.

Library Lockdown was a unique opportunity for Morton-James Public Library to bring something different to Nebraska City. Instead of a one-off program, it brought kids into the library weekly to work together on a major project. Based on informal comments and survey responses, the participants enjoyed the puzzle-based nature and variety of activities that Library Lockdown provided. Local press coverage kept the community interested, and the resultant fully-functioning escape room allows the project to continue to engage (Hannah, 2016a; Hannah, 2016b; Mancini, 2015). It is something that made an impression on these kids and our community, and we most certainly will not forget the wonderful things that can be made by asking the simple question: what if?

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to ALSC and Disney for the generous grant that funded this project. Thank you to our reviewers, Lauren Bradley and Ian Beilin for helping us revise and improve this article.

References

American Library Association (2015, August 25). “$7,500 curiosity creates grant from ALSC.” ALAnews. Last accessed November 2, 2016 from http://www.ala.org/news/press-releases/2015/08/7500-curiosity-creates-grant-alsc

Browndorf, M. (2014). “Student library ownership and building the communicative commons”, Journal of Library Administration, 54(2), 77-93, DOI: 10.1080/01930826.2014.903364

Corkill, E. (2009, December 20). “Real escape game brings its creator’s wonderment to life.” The Japan Times. Last accessed October 31, 2016 at http://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2009/12/20/to-be-sorted/real-escape-game-brings-its-creators-wonderment-to-life

The Escape Game Nashville (2015, May 4). “The History of Escape Games.” Last accessed October 31, 2016 at https://nashvilleescapegame.com/2015/05/04/the-history-of-escape-games

Esquivel, G.B. (1995). “Toward an educational psychology of creativity, part 1.” Educational psychology review, 7(2), pp. 185-202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23359326.

Hadani, H. & Jaeger, G. (2015). Inspiring a generation to create: 7 critical components of creativity in children [white paper]. Retrieved October 16, 2016, from ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277301842_Inspiring_a_generation_to_create_7_critical_components_of_creativity_in_children

Hannah, J. (2016a, March 7). “Morton James Public Library to film zombie movie with new escape room.” News Channel Nebraska. Last accessed October 31, 2016 at http://kwbe.com/local-news/morton-james-public-library-to-film-zombie-movie-with-new-escape-room/

Hannah, J. (2016b, April 9). “Zombies run wild in Nebraska City.” News Channel Nebraska. Last accessed October 31, 2016 at http://ncn21.com/local-news/zombies-run-wild-in-nebraska-city/

Hannah, J. & Swanson, D. (2016, May 25). “Bequettes Solve Escape Room Puzzles to Save Nebraska City.” News Channel Nebraska. Last accessed October 31, 2016 at http://ncn21.com/local-news/bequettes-solve-escape-room-puzzles-to-save-nebraska-city/

Mancini, J. (2015, November 25). “Morton-James receives grant for ‘escape room.’” Nebraska City News Press. Last accessed November 3, 2016 at http://www.ncnewspress.com/article/20151125/NEWS/151129931

Nebraska State Historical Society (2012). “Nebraska National Register sites in Otoe County”. Last accessed October 31, 2016 at http://www.nebraskahistory.org/histpres/nebraska/otoe.htm

Partsch, T. (2016, June 2). “Mayor’s family emerge victorious from library Escape Room” Nebraska City News-Press. Last accessed October 31, 2016 at http://www.ncnewspress.com/news/20160602/mayors-family-emerge-victorious-from-library-escape-room

Pierce, J.L., Kostova, T. & K.T. Dirks (2003). “The state of psychological ownership: Integrating and extending a century of research.” Review of General Psychology, 7(1), 84-107, DOI: 10.1037/1089-2680.7.1.84

Sweetser, P., & Wyeth, P. (2005). GameFlow: a model for evaluating player enjoyment in games. Computers in Entertainment (CIE), 3(3), 3-3.

Thoegersen, R. & Thoegersen, J. (2016). “Pure Escapism.” Library Journal, 141(12), pg 24. http://lj.libraryjournal.com/2016/07/opinion/programs-that-pop/pure-escapism-progams-that-pop

U.S. Census Bureau (2014). “2010-2014 American community survey 5-year estimates.” Last accessed November 4, 2016 at http://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/14_5YR/DP03/1600000US3133705

Pingback : Engaging Youth in Their Local Library | Fall 2016 Information Technologies