It’s the Collections that are Special

In the Library with the Lead Pipe is pleased to welcome another guest

author, Lisa Carter! Lisa has just recently been appointed as Visiting Program Officer to work with the Association of Research Libraries Special Collections Working Group. Read more to learn about her vision and thought-provoking ideas about the future of special collections…

By Lisa Carter

I’m beginning to think that what’s wrong with special collections and archives[1] today is that they are considered special. They are set aside, revered and left as the last great mystery the Library holds. The collections themselves are special in that they are rare, unique, fantastic and archaic and they do need special handling and care. However, our regard for these materials has enabled us to treat them so differently that they are not accessible. We have locked these materials up in our processes and our delivery services, which has kept them out of the mainstream of information available to knowledge seekers. They are only rarely seen as part of the knowledge building conversation[2] and it is because of how we (as librarians and archivists) treat them and present them. We treat them as special in the sense of “separate,” “extra,” “having special needs” instead of special in that they are what make our library special as “distinctive signifiers,” “our enduring core” and “our unique contribution to the world of knowledge.”

A s librarians and archivists redefine ourselves and better articulate how we add value, as we break down long established barriers in our processes, spaces and services, we need to include our most unique collections. We regularly leverage quickly evolving trends in the information environment by refocusing on the needs and preferences of our users in the context of very real competition and economic difficulty. In this framework, libraries can embrace their special collections and archives as a locus of distinction, experimentation and core value. The time has come for libraries to integrate special collections into the flow in every aspect of our work.

s librarians and archivists redefine ourselves and better articulate how we add value, as we break down long established barriers in our processes, spaces and services, we need to include our most unique collections. We regularly leverage quickly evolving trends in the information environment by refocusing on the needs and preferences of our users in the context of very real competition and economic difficulty. In this framework, libraries can embrace their special collections and archives as a locus of distinction, experimentation and core value. The time has come for libraries to integrate special collections into the flow in every aspect of our work.

Distinctive Signifiers

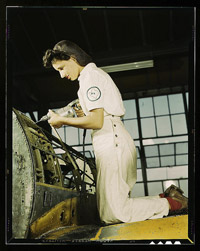

Libraries and librarians are constantly increasing their coolness quotient. American Libraries declares that “The Bunheads are Dead” and celebrates the diversity of backgrounds and work we all do to help people discover information. By adding learning/information commons and coffee bars, participating in social networks, or hiring technically oriented, experimental, responsive, and adaptable information professionals, libraries strive to stay relevant. Special Collections areas and the librarians and archivists working in them are similarly adapting to change, focusing on users and experimenting with technology[3]. In many cases, however, they are going at it independently, because they are in separate departments with the special materials.

Today’s archivists and librarians aren’t just cool because we have mad technology skills, because our place has the best coffee and sweet comfy chairs or because we are über-helpful. We also have the coolest stuff. What is fundamental to our shared purpose, critical to our central mission, and key to our very identity is our ability to connect our communities to knowledge and the raw materials that inspire knowledge; and those resources exist concretely in our collections.

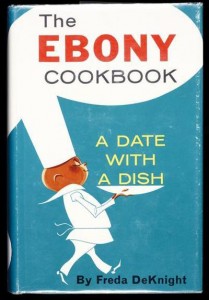

“As we increasingly share a collective collection of books, it is the special collections that will distinguish our institutions.”[4]  The rawest representations of human endeavor and the building blocks of new knowledge are the rare materials and primary sources in our special collections and archives. These collections are often developed around niche interests and grounded in localized expertise. They not only address the specific informational needs of their constituency, but also distinguish their institution in the larger research community. African-American cookbooks are collected at the University of Alabama; Willa Cather‘s manuscripts, letters, and photographs can be found at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln; video and audio records in the Alwin Nikolais and Murray Louis Dance Collection are hosted at Ohio University; and digital assets of teaching and research are held by MIT in DSpace[5]. Public and special libraries also hold collections unique to their communities that distinguish them around the world. The Boston Public Library and the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences are just two high-profile examples. These libraries stand out from their peers because of their particular collections. As Nicholas Barker remarks in his introduction to Celebrating Research, “To be unique in some definable way, however recondite, makes [a library] the object of an attention that it would not otherwise attract.”

The rawest representations of human endeavor and the building blocks of new knowledge are the rare materials and primary sources in our special collections and archives. These collections are often developed around niche interests and grounded in localized expertise. They not only address the specific informational needs of their constituency, but also distinguish their institution in the larger research community. African-American cookbooks are collected at the University of Alabama; Willa Cather‘s manuscripts, letters, and photographs can be found at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln; video and audio records in the Alwin Nikolais and Murray Louis Dance Collection are hosted at Ohio University; and digital assets of teaching and research are held by MIT in DSpace[5]. Public and special libraries also hold collections unique to their communities that distinguish them around the world. The Boston Public Library and the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences are just two high-profile examples. These libraries stand out from their peers because of their particular collections. As Nicholas Barker remarks in his introduction to Celebrating Research, “To be unique in some definable way, however recondite, makes [a library] the object of an attention that it would not otherwise attract.”

Connecting our users to information captured in our collective collections is the shared central challenge in our information-laden, dynamic, instant-gratification environment. As professionals working in libraries with special collections and archives, exposing our singular collections is our unique contribution to the broader world of knowledge. We must do this in the context of trends in the field, including enhancing teaching and learning, increasing efficiency and productivity in creating access, and seizing opportunities presented by technology.

Improving Teaching and Learning

Information seeking is personal. Users can be motivated by the paper that is due the next day, a group with which they identify, or a personal experience or interest. In her November 5, 2008 post on this blog, Ellie Collier discusses “sticky ideas” and the value of simple, unexpected, concrete, credible, emotional stories. Special collections and archives contain locally relevant, unique materials and are a rich source for those kinds of stories. In an academic library, the university archives holds materials from the past that reflect today’s student experience. A public library can connect materials about the immigrants’ lives in the 1900s with the situation of modern-day migrant workers’ families in their community.

post on this blog, Ellie Collier discusses “sticky ideas” and the value of simple, unexpected, concrete, credible, emotional stories. Special collections and archives contain locally relevant, unique materials and are a rich source for those kinds of stories. In an academic library, the university archives holds materials from the past that reflect today’s student experience. A public library can connect materials about the immigrants’ lives in the 1900s with the situation of modern-day migrant workers’ families in their community.

Primary sources and other research materials from special collections can get learners thinking critically about how a source relates to their own information seeking (and generating) behavior. How is a pioneer’s diary about her experiences on the Oregon Trail like a student’s use of Facebook to document her service trip to Costa Rica? What is the difference between the actual text of JFK’s address at Rice University on the nation’s space effort and your local newspaper accounts of it, and how does that compare to watching President Obama’s inauguration speech on YouTube and watching CNN’s analysis of it the next day? By leveraging and analyzing special collection materials to enhance learning experiences, the context of information creation, analysis and transmission can become highly personalized.

As you contemplate your next discussion with your use rs about “the many types of useful information [and] how and when to use them”[6] and engage them in an information source’s “back story,” consider using special collections materials to make your point. Librarians, faculty and archivists should collaborate on instructional opportunities to ensure that all kinds of information sources are considered during research. Integrating special collections into the classroom experience and at the reference desk can significantly enrich the library’s contribution to teaching and learning.

rs about “the many types of useful information [and] how and when to use them”[6] and engage them in an information source’s “back story,” consider using special collections materials to make your point. Librarians, faculty and archivists should collaborate on instructional opportunities to ensure that all kinds of information sources are considered during research. Integrating special collections into the classroom experience and at the reference desk can significantly enrich the library’s contribution to teaching and learning.

Streamlining the Creation of Access

In a time of tightening budgets and web-based information seeking, libraries are reenvisioning the role of and activities around resource description. This shift could directly impact the availability of special collections and archival materials. In Karen Calhoun’s 2006 report on The Changing Nature of the Catalog and its Integration with Other Discovery Tools, she talks about strategies for keeping cataloging relevant including leading resource discovery by developing information systems that “surfac(e) research libraries’ rich collections in ways that will substantially enhance scholarly productivity worldwide.”

On the Record, a report from the Library of Congress Working Group on the Future of Bibliographic Control, provides concrete recommendations for the library field. These include redirecting resources to enable discovery of special collections; creating basic-level access to all unique materials; focusing on practicable, flexible and user-centered description; integrating special collections into discovery arenas; and sharing special collections’ metadata and authority records[7]. To me this is a clear call to action to redirect cataloging resources to expose hidden special collections and archives, and to integrate discovery of these materials alongside that of our other collections.

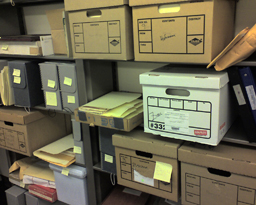

While the broader library world considers directing more resources to exposing hidden collections, the archival community is also working to get more collections into the hands of the users more quickly. In 2003, ARL published the white paper Hidden Collections, Scholarly Barriers,  which notes that “the cost to scholarship and society of having so much of our cultural record sitting on shelves, inaccessible to the public, represents an urgent need of the highest order to be addressed by ARL and other libraries.” Mark Greene and Dennis Meissner’s article “More Product, Less Process” takes the archival community to task for the problem of hidden collections. They suggest that archivists “give higher priority, in practice, to serving the perceived needs of our collections than to serving the demonstrable needs of our constituents.” Many in the archival community are refocusing their processing work to expedite access by undertaking only necessary arrangement, minimal preservation steps and sufficient description to promote use.

which notes that “the cost to scholarship and society of having so much of our cultural record sitting on shelves, inaccessible to the public, represents an urgent need of the highest order to be addressed by ARL and other libraries.” Mark Greene and Dennis Meissner’s article “More Product, Less Process” takes the archival community to task for the problem of hidden collections. They suggest that archivists “give higher priority, in practice, to serving the perceived needs of our collections than to serving the demonstrable needs of our constituents.” Many in the archival community are refocusing their processing work to expedite access by undertaking only necessary arrangement, minimal preservation steps and sufficient description to promote use.

This new focus has cut to the core of activity in Special Collections and Archives. Some Special Collections have focused on creating collection-level records for all collections, processed and unprocessed, for their library catalogs. Others are facing the challenges of providing access to minimally processed or unprocessed collections, such as materials security, researcher frustration and processing on-demand. Archivists are setting aside perfection and learning to embrace the inherent messiness of archival records in order to put access first. This places the onus back on researchers to find specifics and meaning in massive collections. We are redefining ourselves from gatekeepers and interpreters of history to facilitators of access[8].

If we could combine the transformation that is taking place in our cataloging departments with the transition in archival practice, libraries could create a revolution in access. The result will be an explosion of unique descriptive information that could be used to discover distinctive collections worldwide. The original catalogin g skills (analytical and descriptive) that catalogers have honed on circulating library materials can be redeployed (with minimal retraining) to assist with the arrangement and description of significant amounts of unprocessed collections. Aptitude for manipulating, managing and reusing structured metadata can unlock the unrealized potential of our Encoded Archival Description finding aids. Catalogers’ understanding of data normalization and metadata mapping can pull data out of home-grown archival description tools and deposit it in places where it can be manipulable and discoverable in user-friendly access systems. By reenvisioning the work in cataloging and in archives, libraries will be able to offer greater discoverability for their most precious resources.

g skills (analytical and descriptive) that catalogers have honed on circulating library materials can be redeployed (with minimal retraining) to assist with the arrangement and description of significant amounts of unprocessed collections. Aptitude for manipulating, managing and reusing structured metadata can unlock the unrealized potential of our Encoded Archival Description finding aids. Catalogers’ understanding of data normalization and metadata mapping can pull data out of home-grown archival description tools and deposit it in places where it can be manipulable and discoverable in user-friendly access systems. By reenvisioning the work in cataloging and in archives, libraries will be able to offer greater discoverability for their most precious resources.

Web 2.0

Enhanced discoverability can only be truly realized when libraries develop tools that expose the descriptive work of catalogers and archivists to the surface of the Web. This is where those tech-savvy information professionals come in. Many special collections librarians and archivists are trying to open online dialogs about their materials with users. Archives blogs are growing in number (check out the Society of North Carolina Archivists’ blogroll for a sample from North Carolina). However, blogs’ reach still tends to be limited to existing users or those who seek out the archives and exposure is only on highlighted collections.

The Next Generation Finding Aids research group at the University of Michigan is exploring “new online collaborative technologies, such as filtering and  recommender systems, [to] allow for new methods of interacting with and experiencing primary sources.” Statistics from their test bed, The Polar Bear Expedition Digital Collections, demonstrate that even a project with a very limited (but passionate) user base can result in significant attention and engagement, particularly when it comes to users contributing descriptive information about materials.[9] Meanwhile the Triangle Research Library Network (TRLN) in North Carolina is investigating whether indexing Encoded Archival Description metadata in its shared catalog can bring combined discoverability to archival collections as it has for circulating materials. Early challenges have exposed the differences that exist in archival descriptive practice that will need to be overcome to enable cross searching of archival finding aids.

recommender systems, [to] allow for new methods of interacting with and experiencing primary sources.” Statistics from their test bed, The Polar Bear Expedition Digital Collections, demonstrate that even a project with a very limited (but passionate) user base can result in significant attention and engagement, particularly when it comes to users contributing descriptive information about materials.[9] Meanwhile the Triangle Research Library Network (TRLN) in North Carolina is investigating whether indexing Encoded Archival Description metadata in its shared catalog can bring combined discoverability to archival collections as it has for circulating materials. Early challenges have exposed the differences that exist in archival descriptive practice that will need to be overcome to enable cross searching of archival finding aids.

Addressing the challenge from another direction, libraries are realizing increased access after two decades of digitizing their special collections and archives. Digital copies of selected items are available in a wide variety of institution-based digital repositories and content management systems. Many of these efforts have been “boutique” or highly focused projects to digitize cherry-picked items. Just as item-level preservation has been identified as an unsustainable practice in “More Product, Less Process” (MPLP), selective digitization projects have left “our vast collections represented by a relatively small number of gorgeous images, lovingly selected, described, and presented in deep web portals.”[10] If we are to truly explode access to special collections materials, we need to take a less discerning approach to digitizing.

Following on MPLP, libraries are now beginning to test models for mass digitization of special collections materials. Shifting Gears: Gearing Up to Get Into the Flow, an essay reflecting on the Digitization Matters forum, encourages libraries to scan for access, scan on demand, scan whole collections or representative chunks, describe scanned items minimally, and focus on quantity and discoverability. In addition, the authors suggest that “increasing access to special collections needs to be programmatically embedded across the enterprise. Continuing to give these activities ‘special project’ status implies that providing access is not mission-essential.” The bottom line: exposing special collections is not a Special Collections problem; it is an enterprise-wide opportunity.

A few institutions have taken on the challenge. The Smithsonian Archives of American Art received a Terra Foundation for American Art grant to ![[Woman suffrage party] James, Ada Lois, 1876-1952 / Ada James papers, correspondence, 1912, Nov. 8-Dec. 23 Wis Mss OP, Box 17, Folder 3 ([unpublished]) Repository: Wisconsin Historical Society. (From University of Wisconsin Digital Collections) woman-suffrage-party](http://inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/woman-suffrage-party-300x192.jpg) digitize entire collections “with equipment designed specifically for increased levels of production” and to describe materials in aggregations rather than at the item level. The University of Wisconsin Digital Collections has developed a streamlined production model that has reduced their digitizing costs from $1.53 per page to $0.33 per page[11]; however, in usability testing they found that students “reported wanting MORE not LESS metadata.”[12] Experiments with providing digitized images with minimal metadata embody the sacrifice made when choosing quantity over quality.

digitize entire collections “with equipment designed specifically for increased levels of production” and to describe materials in aggregations rather than at the item level. The University of Wisconsin Digital Collections has developed a streamlined production model that has reduced their digitizing costs from $1.53 per page to $0.33 per page[11]; however, in usability testing they found that students “reported wanting MORE not LESS metadata.”[12] Experiments with providing digitized images with minimal metadata embody the sacrifice made when choosing quantity over quality.

The Library of Congress found that enlisting users in the description of materials may counteract the initial lack of rich item-level  metadata. As reported in For the Common Good the Library made two collections of photographs available online in the Flickr Commons, inviting users to contribute enhanced descriptions. According to the report, “7,166 comments were left on 2,873 photos by 2,562 unique Flickr accounts. …. More than 500 Prints and Photographs Online Catalog (PPOC) records have been enhanced with new information provided by the Flickr Community.” With engagement like that, why agonize over description and subject headings? The ability of users to connect with collections on this personal level also increases their sense of ownership and relationship to history. Knowledge-building is borne out of this kind of personalized learning.

metadata. As reported in For the Common Good the Library made two collections of photographs available online in the Flickr Commons, inviting users to contribute enhanced descriptions. According to the report, “7,166 comments were left on 2,873 photos by 2,562 unique Flickr accounts. …. More than 500 Prints and Photographs Online Catalog (PPOC) records have been enhanced with new information provided by the Flickr Community.” With engagement like that, why agonize over description and subject headings? The ability of users to connect with collections on this personal level also increases their sense of ownership and relationship to history. Knowledge-building is borne out of this kind of personalized learning.

Additional archives-based efforts to expose unique collections in the Web 2.0 environment are listed on the ArchivesNext blog. To most effectively contribute their distinctive building blocks of knowledge to the broader research environment, however, libraries cannot relegate digitization and discovery innovation to special projects in Special Collections. Alongside realigning the description and data-structure expertise provided by catalogers, libraries must apply the technical, programming and development proficiency in their information technology departments to this challenge. The expertise cultivated in reference, instructional, outreach, and collection-management staff is also critical to insuring that these efforts are relevant in addressing users’ needs.

Convergence

For libraries to contribute effectively to knowledge-building in their communities, the constructed partition that has set special collections aside as “special” must be dismantled. It is time to integrate the selection, description, research service and technological activities in every library with those needed to connect users to our most distinctive, unique collections. Libraries must recognize that while the collections are special and even have special needs, the talents and skills needed to expose them are found library-wide. Additionally, many special collection materials are now born digital and do not require physical segregation in our traditional Special Collections units. Further, enterprise-wide effort is even more critical to born-digital collections’ exposure and survival. Users just want the best information for their task and they want it to be available all in the same place.

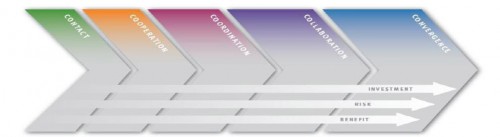

The Research Library Group outlines a continuum of collaboration in libraries, archives and museums (LAMs) that begins with contact between two entities, moves through cooperation and coordination to collaboration and eventually arrives at convergence. As LAMs move through the continuum, they grow towards shared investment and risk, but realize more profound benefits. When collaboration becomes convergence, shared activity becomes infrastructure.[13] In today’s libraries, we need convergence around special collections that erases our existing silos.

Special Collections and Archives may sense a loss of their unique identity during such a transformation. Partners in other library units may resist activity previously outside their purview. Yet sharing responsibility for our distinctive, valued and unique collections will raise the profile of the whole library and, most importantly, benefit our users.

Special collections  reflect our enduring identities by defining who we were, informing what we will become, and distinguishing our communities. As critical components in the knowledge conversation, special collections must be integrated with other resources, and exposed in the same venues and pathways. As collections that each library can uniquely contribute to the overall research and learning environment, they must be mainstreamed and acknowledged as mission-critical. It is only the collections that are special in Special Collections, not the work of making them accessible and not our users. For the sake of our users and our libraries we need to stop treating them separately.

reflect our enduring identities by defining who we were, informing what we will become, and distinguishing our communities. As critical components in the knowledge conversation, special collections must be integrated with other resources, and exposed in the same venues and pathways. As collections that each library can uniquely contribute to the overall research and learning environment, they must be mainstreamed and acknowledged as mission-critical. It is only the collections that are special in Special Collections, not the work of making them accessible and not our users. For the sake of our users and our libraries we need to stop treating them separately.

What you can do:

- Selectors, collection managers and branch librarians, talk to the curators in Special Collections and Archives about how you can help with strategically targeted collection building efforts. What makes a relevant, distinctive collection in your community?

- Catalogers and metadata experts, discuss the metadata generation, manipulation and transformation needs for special collections with lead processors. You’d be surprised at how much assistance you can provide but be prepared to face big challenges and quantities.

- Access and delivery services, you can’t imagine the expertise you can share regarding collection maintenance, security and tracking until you have that cup of coffee with the reference staff in Special Collections.

- Reference and information services, engage your Special Collections colleagues in your instruction activities. Consider cross-training on the reference desks, offer to cover a reference shift in Special Collections. Special Collections and Archives folks, rotate into service on the main reference desk.

- Information technology, imagine the opportunities! There are databases, finding aids and home grown systems to integrate, improve and streamline. Let Special Collections offer you a challenge that will make managing server space and device inventories look easy.

- Digital initiatives, if you want content, we’ve got content. Allow Special Collections to be your playground for implementing new, cool tools. We’ve got digital objects coming out of our ears. Can you get them onto desktops, mobile devices and course management systems?

- Special collections and archivist colleagues, share your most interesting challenges, be willing to let others muck around in your stuff, be articulate and practical about your needs and think creatively about what you have to offer your colleagues in return.

Thanks to Josh Ranger and Bill Landis for their ideas, feedback and careful reading of a draft of this piece and to Hilary Davis and Kim Leeder from ItLwtLP for their encouragement, questions and suggestions for each version. Thanks to Hilary and Brett Bonfield for last minute technical assistance. Special thanks to Ben Carter who stayed home to provide technical support and thwart bad behavior plugins.

[1] In the spirit of this piece, I try to distinguish between special collections, the collections, and Special Collections, the unit of the library, by capitalizing when I am referring to the unit. Special Collections and Archives can be departments in a library or institution; special collections belong to the whole institution.

[2] For an interesting discussion on the knowledge building conversation and the library’s role in participatory networks, read the Information Institute of Syracuse’s technology brief Participatory Networks: The Library as Conversation for ALA. Not only do they envelop special collections as key aspects of the conversation but they also address the importance of innovating technology “at the core of the library.”

[3] For more on reenvisioning archival identity, see Mark Green’s inaugural presidential address for SAA “Strengthening Our Identity, Fighting Our Foibles.”

[4] Quoted from Ricky Erway’s “Supply and Demand: Special Collections and Digitisation” for Liber Quarterly, 2008. Many variations of this sentence have been appearing in various commentaries since the publication of ARL’s anniversary publication Celebrating Research with Nicholas Barker’s persuasive introduction.

[5] These collections (and more) were highlighted by their institutions as distinctive signifiers of their collections for ARL’s Celebrating Research: Rare and Special Collections from the Membership of the Association of Research Libraries in celebration of the Association’s 75th anniversary.

[6] Quoted from Ellie Collier’s “In Praise of the Internet: Shifting Focus and Engaging Critical Thinking Skills” In the Library with the Lead Pipe, January 7, 2009.

[7] Found in Recommendations 2.1.1-2.1.5 on pages 22 and 23 of the Library of Congress’s On the Record.

[8] The self identification of archivists as “gatekeepers of history” is interrogated by Barbara L. Craig, in “Canadian Archivists: What Types of People Are They,”, Ann Pederson, “Understanding Ourselves & Others: Australian Archivists & Temperament,” and Charles R. Schultz, “Archivists: What Types of People Are They?” Provenance 14: (1996).

[9] For more on the Polar Bear Expedition Project, please refer to the article by Magia Ghetu Krause and Elizabeth Yakel, “Interaction in Virtual Archives: The Polar Bear Expedition Digital Collections Next Generation Finding Aid” American Archivist 70:2, Fall – Winter 2007, pages 282-314.

[10] Quoted from Ricky Erway and Jennifer Schaffner’s Shifting Gears: Gearing up to Get Into the Flow from OCLC Programs and Research, 2007.

[11] Which Joshua Ranger told us at the 2006 MAC Fall Symposium.

[12] Reported at the SAA Meeting in 2008 and in a handout to OCLC’s Member’s Council in February 2008. While the work at the The Smithsonian Archives of American Art is groundbreaking in scope and methodology, Ranger’s work explores how any library can make an effort towards quick and dirty digitization and the ramifications.

[13] For more on the collaboration continuum see Beyond the Silos of the LAMs: Collaboration Among Libraries, Archives and Museums by Diane Zorich, Gunter Waibel and Ricky Erway for OCLC Programs and Research, 2008.

Pingback : Opening Access to Special Collections and Archives…02.11.09 « The Proverbial Lone Wolf Librarian’s Weblog

I have been involved in an ongoing conversation with the librarian in charge of our college archives here. It revolves around why the archives are only cataloged in our web opac at a very high level (box or set of boxes), not down to the individual item. I continually ask her how people are going to find what is in the archives if it is not cataloged in the same way as our books, videos, or serials. She keeps telling me that people who research archives do it in person. It tends to be a very circular argument.

Wilfred, it’s great that you are having that dialog! One way to think about it is to compare the description of a collection to the cataloging of a book. Items in collection (letters, photos, videos) could be seen as pages of a person’s life or an organization’s activity. The aggregate has meaning as a whole and sometimes we provide a table of contents (which we call series-level or folder-level inventory). But just as a cataloger would never catalog each page in a book, archivists try to avoid describing each item. The main reason for this (in addition to not having the resources to describe at the item-level) is that context is critical. As with pages, the materials around the item give it more meaning and the group of materials should be used together. The researchers gain more knowledge if they “read” the collection for themselves. Further, we never know what a researcher will find most valuable about a collection. One person might have one use for a set of letters while another has a completely different use. Trying to anticipate what is most valuable leads us to a granular level of description that is not helpful to the researcher and unsustainable as a practice. Does this help?

Hi Lisa – thanks for sharing your vision for “special” collections! I’m wondering what your thoughts are as to the potential impact (if any) of the Google Books project (that was described last week in this blog) on the visibility/relevance of archives/”special” collections content?

In reply to Lisa, It makes sense. It is the sometimes provide a table of contents that bothers me. That table of contents is not searchable on our online catalog. In my mind it must be.

@Wilfred – I agree with that. We are working on that challenge in our institution as well.

@Hilary – Well, I hope the Google Books project means that as more books become accessible online through GBP, libraries will be able to turn more of their resources to working on special collections. It goes back to the idea that as the materials that libraries commonly hold (circulating books, journals, media) become more and more available online what will make a library distinctive is their local, unique, special collections. Plus Google is providing a demand situation that should make more libraries want to digitize more of their special collections so that they have something special to offer the conversation that they can claim as their own.

Lisa, thanks for the great post. I wonder if the increasing digitization of Special Collections will in large part solve the problems of cataloging those items. For a long time I’ve been watching the digital collections feature in AL Direct (the ALA email newsletter) and the list of links I have at this point is really impressive! Of course I expect that very few libraries will ever be able to digitize their entire archives, but if every library managed to get through their most notable collections — which seems to be what’s happening out there? — things are going to change dramatically. The next question in my mind is: do we rely on Google to search and find all those disparate digital collections, or is there some WorldCat equivalent we can create to search all of them?

Kim, I hope so. I’m wondering if we digitize special collections, entering only the metadata necessary to get them online, can people describe them from the digital copy? LC has shown us that communities will rally to enhance metadata if we only provide limited. As for relying on Google, I think we have to expose these collections through Google. At the collection level, we can provide access through WorldCat. Also, RLG (now with OCLC) has ArchivesGrid (http://archivegrid.org/web/index.jsp). There’s some buzz for doing a union catalog or census of collections, but some argue that we should spend our time exposing the collections where the users are: Google, Flickr, YouTube, etc. Me, I think that anywhere you can expose them, you should.

Lisa,

I’m pleased to see that you’ve been handed a baton (albeit in the form of lead pipe!) to help raise awareness and critical knowledge about what makes special collections special – namely the collections themselves.

What your post shows so clearly, in fact, is that the challenges that special collections librarians and archivists face in trying to make their collections more discoverable and accessible are in many ways the same challenges that librarians who manage general collections also face. Increasingly, it is how collections are connected to online services at the network level that makes all the difference in who finds them and how they are used.

For those of us who have spent most of our careers working in and around academic libraries, we have witnessed a shifting of responsibilities that points toward a shifting of mission that has not yet been fully appreciated, especially by our parent institutions.

Whereas research libraries previously existed and were managed to provide maximum benefit to the faculty and students of the parent institution, global networking systems have exposed them to the larger world, which can now claim them — rightly, I think — as common cultural (intellectual, scientific, literary, etc.) assets from which everyone ought to be able to benefit. And this goes for “general” collections as well as “special” collections, where the most valuable volume is generally the one you can get to quickest.

It is the development of the global information economy that is the main responsible for this shift, even as research libraries have been shifting a lot of their resources into placing their collections in the networked information stream. Yet for all their doings, it seems to me that research libraries have not yet managed to claim a viable stake in the evolving economy, one that will carry them forward with continuity into the future. Ownership of physical collections is one asset, but ownership and control of information about those collections and ability to deliver it quickly and easily is arguably the greater asset.

I’m all for exposing collections at the network level but I do have some concern that unless research libraries can find a more direct means of tapping into the information economy that their ability to do what they have done so well for so long will be diminished. The institutional budget crises that are being precipitated by the now global recession are likely to prove a real test in this regard. Will the choices we make now in the face of economic hardship be creative ones that help us to thrive in the future or will they tend to force foreclosures of our options and opportunities we have to expand the mission of research libraries to the global level where they are demanded?

I’d be curious to know if you or others who read your post also see the situation I am trying describe.

Christian- Well, that’s the trick isn’t it? Are our institutions going to be able to identify what is mission-critical to moving forward and invest in dramatic change? Or are they going to hunker down and protect “what we’ve always done” first? I guess a lot of it is how you define mission-critical and I think tapping into the info economy is key. I’m interested in your reference to “deliver it quickly and easily”, it means fundamentally changing from quality to quantity doesn’t it?

*nods vigorously*

I couldn’t agree more with the bulk of this post. My one concern is that many of these goals are more easily achieved at larger institutions that have more institutional resources, both in terms of finances, and staff time and expertise. I’d *LOVE* to have much more of my special collections online (50,000 public domain dime novels, anyone?), but the resources to digitize, mark up, and make available in bulk just aren’t there (yet).

So Lynne, does that mean you couldn’t engage your reference, circulation or cataloging staff in digitizing those dime novels? Or do you not have enough of those resources either? I do agree with you that it’s easier to shift resources around at a larger institution.

Lisa,

Your advice to Lynne (Hi Lynne!) points to what I was going to say in response to your comment on my posting about shifting emphasis from quality to quantity in order to tap into the information economy and provide broader access to our collections.

At the heart of your suggestion to Lynne to engage her reference, circulation or cataloging staff in digitizing dime novels is the principle of distributed workflows. Certainly one impediment to getting more done in special collections is staffing. Yet if we analyze what work actually needs to get done and then what skills and equipment are needed to do it, I think we’ll find that much of it does not necessarily need people with special collections and archival experience. Nor does it necessarily need to be done in special collections secure areas.

The problem comes precisely with engaging the commitment of other staff, as that is typically a managerial function beyond the control of the special collections department head. Higher levels of administration are typically the areas need to be engaged to get this kind of collaboration to happen. But special collections librarians can do a lot to make the case and to offer proposals of new types of workflows that will help to ensure that backlogged collections get cataloged and processed, that images get scanned and metadata encoded, and that researchers are served. Perhaps the new ARL working group report on special collections will help administrators better understand the potential of special collections to serve their institutional missions and encourage them to allocate staffing in creative ways to better support them.

Ensuring that special collections “products” (e.g., information about collections and digital collections) get delivered quickly and easily means getting them into systems that operate at the network level with network-level efficiency. From there, we need to find ways to connect users and what they find with our institutions and knowledgeable staff. Making that connection, which involves managing relationships with our users, is where the quality real comes in.

Quality cataloging and metadata description is important, but users really only need enough to find resources using the simplistic strategies they typically employ. Users do not necessarily want to be trained in how to create more complex and more powerful searches that takes advantage of sophisticated and deep metadata encoding schemes; rather they want to be able to type a few words into a search box and quickly see results that they can start sorting through, comparing and using as the basis for refining or launching new searches.

Users also want to be able to ask questions of knowledgeable experts once they get into a search process. That’s where libraries need to be able to step in provide easy links to their services and staff. Service quality is every bit as important as data quality in conditioning the user’s perception of quality and institutional trust.

Christian

Christian – I like your observation that the quality in service/discoverability may be more important than granular metadata. A focus on service is exactly the point. But I’ve always had the question, how do we know how much is enough description for the users “to find resources using the simplistic strategies they typically employ”. How do we know what is “necessary”, “minimal” and “sufficient” (to reference MPLP again)? –Lisa

Lisa,

Did you happen to receive Terry Belanger’s annual Rare Book School Valentine Thought poster? The quotation this year is “You never know what enough is until you know what is more than enough.”

Funny, but true, and maybe applicable here.

It seems to me that one way to figure out what descriptive information is sufficient is to analyze user search behaviors to learn what information they are not taking advantage of. This can be done with qualitative methods, like focus groups and direct observations of individual search behaviors, but I expect it can be done more effectively with the quantitative analysis. Think of how Google and other search engines analyze your search behaviors and you get the idea.

If we find that user searchers are not taking advantage of certain types of data, then maybe we don’t need to provide it, or provide it in every case by default.

Lisa,

Thanks for mentioning Lorcan Dempsey’s recent article in First Monday:

http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2291/2070

A propos of our conversation here, I was struck by the following paragraph under “Some Issues for Libraries”:

“Services. As a growing proportion of library use is network–based, the library becomes visible and usable through the network services provided. On the network, there are only services. So, the perception of quality of reference or of the value of particular collections, for example, will depend for many people on the quality of the network services which make them visible, and the extent to which they can be integrated into personal learning environments. Increasingly, this requires us to emphasize the network as an integral design principle in library service development, rather than thinking of it as an add–on. The provision of RSS feeds is a case in point. Thinking about how something might appear on a mobile device is another.”