Are You Worth It? What Return on Investment Can and Can’t Tell You About Your Library

Photo by Flickr user cambodia4kidsorg (CC BY 2.0)

“The indicators that served as benchmarks in the past, such as number of volumes and number of journal subscriptions, are no longer sufficient because of the more expansive role that the contemporary library has assumed” (Weiner, 2005).

“The measurement of quality will come back to the questions of who are the users, what are the inputs, what are the outputs, do we produce the outputs in a way that meets the needs of the users, and what do those outputs contribute to the productivity and accomplishments of those users?” (Pritchard, 1996).

By Cory Lown and Hilary Davis

It’s almost a sure bet that your friends, family and colleagues are looking at ways to save money and, in general, are tightening the purse strings a little more these days. The post on January 14, 2009 in this blog reviewed the state of libraries during recessions and pointed out the growing news pieces that remark at the huge surge in library usage. People are realizing real savings by relying more and more on libraries. Ask yourself how much do you spend at bookstores and music shops such as Amazon and Barnes and Noble each year? Magazine subscriptions? Internet service? Entertainment like movies and concerts? If you had to go without one or more of those services, think about how much you could save by relying on your local library to provide access to those services and content streams. At the same time, libraries of all types are faced with the inevitability of budget cuts due to the recession and must justify the use of existing funds for programming, staff, services and collections. Take a second and google ‘return on investment and libraries’ to get a sense of the importance of demonstrating library value.

In order to have the financial ability to continue providing those services and content streams, libraries need to prove to their funding sources, whether tax-payers, private donors, universities, governments, schools, or corporate parents, that those services, programs and collections are meeting users’ needs. Moreover, libraries must prove without a doubt that the funds provided to libraries to develop those services, programs and collections provide a good return on investment.

While there are many metrics for assessing library value (e.g., LibQual, circulation trends, gate counts, usage statistics trends, ARL Annual Statistics, etc.), this article aims to explore the return on investment (ROI) approach used by libraries to demonstrate value.

What is Return on Investment (ROI) and how is it used by libraries?

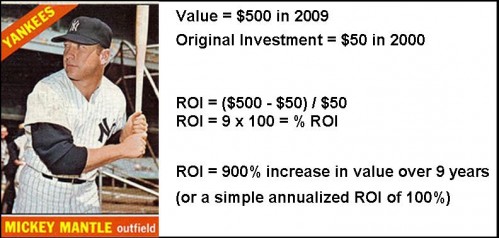

Return on investment (ROI) is how much you get back for what you put into something. Strictly speaking, ROI is based on dollars and cents. So, you need to be able to quantify how much money was invested in something and then you need to compare how much money is gained or lost as a result of how the investment was handled. There are two kinds of questions that ROI is good at answering. One is: how much money will be gained by investing in a particular financial asset? The other is: will putting resources into a project or service yield a measurable benefit? Let’s take a look at a quick example using a baseball card. If you bought a baseball card in 2000 for $50 and now in 2009, it’s worth $500, what is your return on investment?

In libraries, ROI is measured in many different ways. ROI can be used to measure the costs (investment) and the outcomes (the return on investment) from the perspective of library users, the parent organization, or from the perspective of the library itself. Costs are typically dollars spent on a service or resource and/or time spent to provide or access a service or to acquire or use a resource. The returns on an investment can be either outputs (the result of a service or resource such as expanded journal collection), uses (how the service or resources are used), or outcomes (indirect results of the output or the use such as time saved) (Jose-Marie Griffiths, 2007).

Motivations for using ROI in libraries

ROI can be an integral part of the process for evaluating a library’s services, collections, staffing levels, planning for new services and resources, or measuring how valuable your library is to your community and stakeholders.

For example, for libraries supported with public tax dollars, one way to use ROI is to measure tax dollars (the investment) against the benefits (savings by not having to pay elsewhere for the use of library materials and services). Library ROI studies consistently suggest that public libraries give a high return on investment, providing anywhere from $2 to $10 in return for every tax dollar received.

- In Florida: for every $1.00 of taxpayer dollars spent on public libraries, income (wages) increases by $12.66

- In South Carolina: In return for an investment of $77.5 million, public libraries pump $347 million into the state’s economy

- Can you say your library users derive more than $4.00 in benefits for every $1.00 spent of taxpayer money? St. Louis Public Library can!

[From Trustee Blog: Library ROI – What’s Your Community rating]

Strategies for measuring ROI in libraries

Calculating a return on investment may seem straightforward until one considers the kinds of costs and returns associated with libraries. Measuring returns first requires that the organization have a clear sense of its mission and objectives. It is not possible to measure benefits unless one can identify the value an organization aims to provide. There are several classes of returns, direct and indirect, and individual and collective. In general, direct, individual benefits are easier to measure and quantify than indirect and collective benefits. This poses a challenge for libraries, as many of the benefits libraries provides are indirect and collective, such as the value of having a better-educated citizenry.

Jose-Marie Griffiths has conducted several return on investment studies in public and special libraries. In a presentation at the Special Library Association Annual Conference (2007), Griffiths outlined a method for calculating ROI in special libraries that demonstrates the kinds of factors that should be taken into consideration. Costs are generally straightforward, and include overhead and the costs of the users’ time associated with utilizing the library, but returns are trickier. Griffiths argues that libraries should use contingent valuation for assessing benefits. Contingent valuation is a method for evaluating goods and services that are not priced. It involves assessing the effect of taking the service away. This could mean attempting to calculate the costs that would be borne by users if they could not use the library. Griffiths also notes that changes in productivity and information needs that would go unanswered should also be considered.

Using ROI, libraries can try to place a value on the services they provide and the collections that they make accessible. For instance, many ROI studies compare the cost associated with borrowing an item from the library versus individuals having to purchase that item on their own. Consider the costs associated with the library providing a DVD that is worth $20 that circulates 50 times in a year. If each library user had to purchase that item, the collective cost would have been $1,000. Of course, there are additional costs borne by the library for providing the DVD than just the $20 investment, including staffing, storage, and preservation.

Photo by Flickr user allaboutgeorge (CC BY 2.0)

Libraries can also be valued in terms of savings of entertainment costs to a community—public film viewings, author readings, and workshops are freely offered services provided by libraries. Many libraries also offer classes, which can be viewed as a cost savings to the community as well. Classes on Microsoft Office programs, general computing, financial planning, and job hunting strategies are often offered for free at libraries. Libraries are also valuable to communities as employers of citizens and as contributors to the local economy.

Examples from different library contexts

Public libraries

Most ROI studies in libraries have focused on public libraries. A fantastic inventory and review of value-demonstration methods and metrics is available from the Americans for Libraries Council: Worth their Weight: An Assessment of the Evolving Field of Library Valuation (2007). We will highlight a few examples here.

The “Public Library Benefits Valuation Study” conducted by the St. Louis Public Library in 1999-2001 used cost-benefit analysis techniques. First, they calculated a comparison between local taxes invested in library services and direct benefits provided to users. Across the five urban, public libraries included in the study, for each $1 of annual taxes invested in the library, library users received between $1.30 and $10 in benefits. This varied widely among the libraries in the study. Second, the study looked at returns in terms of capital investment. This compares the total investment in a library’s capital (buildings, vehicles, furniture, and other assets) with the benefits received by users. Annual returns on capital investments ranged from 5% to 150%, again varying widely among the public libraries in the study.

The State Library and Archives of Florida conducted a taxpayer return on investment study of Florida public libraries. Overall, the study found that for every $1 invested in the library at least $6.54 is returned. Other findings show that for every $1 invested in the library the Gross Regional Product increases by $9.08 and wages increase by $12.66. They also estimate that for every $6,488 invested in the library, one job is created. Statewide, the study estimates that the Gross Regional Product is increased by $4 billion as a result of taxpayer investment in Florida public libraries.

Many other public libraries have reported return on investment information, including New York public libraries, Pennsylvania public libraries, South Carolina public libraries, and Wisconsin public libraries, among others. Return on investment results from these studies ranged from $2.38 in Indiana to $5.50 in Pennsylvania. Among the five states with published ROI studies, Indiana, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Florida, the average ROI is $4.99 for every $1 invested.

Another approach some libraries have taken is to provide calculators on their websites that let users estimate how much value they are getting from the library based on their own use of its services (e.g., Rhode Island).

A potential hazard of ROI studies is that they produce what appears at face value to be a simple metric that can be compared across libraries.

Photo by Flickr user msmail (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

It is critical to reiterate that the ROI studies that we use as examples specifically state caveats that those ROI metrics are estimates that are based on surveys of their own local users combined with metrics that are relevant to their own budget systems. Any attempt to compare ROI metrics across these boundaries doesn’t make sense and is not relevant. The new LJ Index, while not specifically ROI-focused, attempts to correct the problem of peer comparison by removing the metrics that are specific to local contexts. Instead the LJ Index focuses only on measurable outputs such as circulation per capita, visits per capita, program attendance per capita, and internet use per capita. The LJ Index is one of several models for ranking public library quality, and is unique in that it enables statistically valid comparison across libraries. However, it removes the context-sensitive framework that enables libraries to show a return on investment of money and resources.

For ROI library metrics, the point isn’t that putting more and more money into libraries will yield ever increasing returns. The point is to show that libraries are providing value for the money that is invested in them. Those investments should be commensurate with the needs of the communities they serve.

Academic libraries

University libraries have fewer models to emulate. In 1996, Sarah Pritchard described the problems associated with assessing the value of academic libraries. She claims that the lack of standards and repeatable methods for demonstrating value (such as support of accreditation reviews, educational assessment and outcomes, ranking of graduate programs, success of job attainment after graduation, success in attracting donors, and faculty research productivity as measured by grants and publications) makes it impossible to conduct studies that compare library value across institutions.

A recent study (Luther, 2008) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign addresses some of Pritchard’s concerns about demonstrating ROI in academic libraries. Unlike public libraries, which focus on the value of services, the Illinois study examines the library’s contribution to revenue-generating activities of faculty by examining the role of library-sourced citations in grant applications. The model for the study is that the library’s investment in materials increases researchers’ productivity. This increase in productivity produces a measurable increase in grant receipts due to increased citations, as well as recruitment and retention of productive faculty.

To calculate the dollar value returned to the University of Illinois in the form of grants due to investment in the library, the faculty was surveyed to determine the importance of citations in securing grants, the percentage of faculty who use citations in grant applications, and the percentage of citations obtained through library-subscribed resources. The model also accounts for the proportion of grants that are funded. The study found that for every $1 invested in the library, $4.38 in grant income is generated for the university. This model purposefully avoids attempting to measure the social value or increases in productivity attributable to outcomes from use of the library resources.

Special libraries

Special libraries such as those found primarily in the government and corporate sectors tend to focus their ROI metrics on time saved for employees by using library resources and expertise, increases in revenues, decreases in research and development expenses, productivity gains, and cost savings. Roger Strouse, Director of Outsell, Inc., writes extensively about the value and application of ROI studies for special libraries. Outsell conducts studies of market trends in the publishing, education, and information industries. In its 2007 study on corporate, government, and medical libraries, Outsell found that the average time saved for users was 9 hours per library visit/interaction. They also reported that not only do corporate libraries save $3,107 per use of library resources and services, but also that $6,570 worth of revenues were generated with the aid of library resources and services.

“Being good at what you do and at the services you provide is no longer good enough. Very good information centres will be cut, and may be outsourced or offshored, not because of their inability to provide good services, but because of their inability to demonstrate an ROI or provide evidence of the impact they make on their organizations” (Boyd Hendriks and Ian Wooler, 2006).

Outsourcing remains a serious threat to many special libraries. Integrating and aligning the work of special libraries with the risks associated with the parent organization is one of the key recommendations of corporate library strategists. Collaborating on the reduction of risk, delays, and workplace injuries is seen as a way to position a library as a value-added partner and a key component in the success of an organization. Strouse (2003) provides an example survey for special libraries to use in measuring ROI that includes questions about types of projects for which library services and resources were used such as patents, new technologies, new product acquisitions, and changes in marketing strategies. The Special Libraries Association maintains a summary of articles and presentations on ROI metrics and value-demonstration strategies (the full bibliography is available to SLA members).

A Few Caveats

There are some reasons why ROI might not be the best tool for demonstrating library value. In some cases, a strict ROI metric may demonstrate that a library is not providing a good return on investment. Elliott, et al. (2007) describe the pros and cons of conducting an ROI or cost-benefit analysis. Many of the benefits they describe are covered earlier in this article. However, one of the disadvantages of ROI or cost-benefit analyses described by Elliott, et al. is that these metrics cannot be used for peer-comparison. The metrics are created using value systems and context-sensitive data that pertain to individual libraries. Pritchard (1996) echoes this problem in the realm of measuring academic library quality and effectiveness:

“The difficulty lies in trying to find a single model or set of simple indicators that can be used by different institutions, and that will compare something across large groups that is by definition only locally applicable—i.e., how well a library meets the needs of its institution.”

Elliot, et al. (2007) also warn against applying these kinds of metrics to small libraries: “Efficient operating costs do not appear to rise proportionally with cardholder population and collection size. Thus, benefit-cost ratios for well-managed larger libraries tend to be higher, in general, than those for well-managed smaller libraries. Larger libraries also are more likely to be able to accommodate the expense and technological requirements associated with a CBA [cost-benefit analysis] study.”

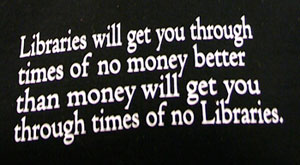

There are more subtle reasons to not rely on ROI metrics alone, and to be careful about interpreting ROI. Organizations need resources to survive. Not-for-profit organizations, whose missions are based on soft values or moral ideas rather than monetary profit, must be supported by private donations, government, or by the organizations that they support. The values of the library—ubiquitous access, preservation, and organization of information—are prone to differing interpretations of importance. Put bluntly, the library must show that the Internet has not rendered it obsolete. Libraries will be stronger if they can demonstrate their value in terms which those that provide its funding understand. In the culture and time in which we live, “value” is understood most readily in monetary, economic terms.

Making it even more difficult for academic libraries to demonstrate their worth, the mission of the library is tied to the mission of the university at large. Academic libraries must demonstrate their contributions to the mission of the organization of which they a part. And they must also attempt to make a long-term argument about preservation of information and investment in human capital to an audience that is focused on the present bottom line. Can we articulate the importance of what we do in terms that non-librarians can understand? If we cannot articulate what we are doing then we must first go back and redefine what our mission and purpose is, clearly and succinctly, before we can attempt to measure our effectiveness and value.

It is, however, essential to remember that there is a reason why libraries do not operate for a profit (with the possible exception of libraries that charge back to users for services), and that they came into being for reasons other than generating monetary wealth. There are also good reasons to be skeptical of measurements of library quality, performance, and relevance presented in purely economic terms. Discussing the role of non-profit organizations in general, Eikenberry claims:

Because of their inherent value, it is extremely important for nonprofit organizations to focus on their organizational missions…They are more than just tools for achieving the most efficient and effective mode of service delivery; they are also important vehicles for creating and maintaining a strong civil society. (Eikenberry)

Libraries must strike a balance between focusing on their mission and on their desire to prove worth in terms of high performance and ROI. For many libraries, ROI simply doesn’t measure the indirect benefits they provide.

Librarians must be particularly creative in the ways that they think about how their libraries perform and what they contribute to the populations they serve. For example, does having an appealing library make a university more appealing to potential students? One study suggests that libraries have a significant influence on students’ decisions to go to a particular university—53%—second only to “Facilities for Major” (e.g., labs, studios, etc.) at 73%.

U.S News and World Report’s rankings of colleges and universities, has transformed the way students select schools. Traditional ROI studies do not account for a library’s impact on the reputation of its university or college as a whole, but a study by Weiner in 2009 makes a case for the library’s contribution to the reputation of the university it serves. The study finds that library expenditures are a significant predictor of institutional reputation.

Weiner argues that this finding means that, in fact,

“the disintermediation caused by the rapid increase in online access to information does not seem to have displaced the library. These results suggest that libraries in the doctoral institutions included in the study may have adjusted and found solutions to unprecedented external pressures.”

Weiner sees the libraries’ position as one of “boundary spanning,” meaning that it brings together researchers and students from across the campus in ways that no other organization on the campus can. Studies such as this one are vital for libraries, as they give evidence that libraries contribute to their parent organizations in unexpected ways. By contributing to an institution’s overall reputation, libraries also impact real economic outcomes from that reputation: such as attracting better students, retaining top-notch faculty, and attracting donors. Being able to articulate this kind of impact may help university administrators listen a little more closely.

It is vital that libraries demonstrate both the monetary value and as well as the social value of their services. ROI is one part of a suite of tools librarians can use to demonstrate performance and value. Relying on ROI alone to communicate and demonstrate the value of libraries may very well undermine the core purposes libraries serve and the indirect benefits they bring. Libraries undertake many tasks that are invisible to the casual user. They handle licensing of journals, negotiating with vendors and publishers for access to content, selecting resources. Libraries also contribute to the prestige of the institutions they serve by helping to attract top researchers, faculty, and students. Academic libraries and public libraries, especially, serve as unique third places within their communities, where people who would otherwise not interact come to work and learn in the same space. It’s up to us to convince our users and our sources of funding that we’re worth it. ROI studies aside, one of the best things we can do to show our worth is to provide great services that help our users work more effectively.

We hope this post will generate some lively discussion about the role of ROI in libraries, and also generate ideas about what libraries can measure to demonstrate their value. What has your library done to measure its value?

Thanks especially to Brett Bonfield, Greg Raschke and Katie Wheeler for their comments and for reviewing and editing various drafts of this article.

Conferences, Seminars, Upcoming Events on ROI and Libraries

- Computers in Libraries – Track E (Planning and Managing): What’s the Return on Investment for Your Library? April 1, 2009

- ALA Annual Conference Surviving in a Tough Economy – An Advocacy Institute Workshop July 10, 2009

Further Reading

- Abram, Stephen. 2007. The Value of our Libraries: Impact, recognition, and influencing funders: http://www.sirsidynix.com/Resources/Pdfs/Company/Abram/ArkansasLA_Value.pdf

- ALA. 2009. Articles and Studies Related to Library Value (Return on Investment): http://www.ala.org/ala/aboutala/offices/ors/reports/roi.cfm

- Cain, David and Gary L. Reynolds. 2006. The Impact of Facilities on Recruitment and Retention of Students. Facilities Manager, March/April: http://www.appa.org/files/FMArticles/fm030406_f7_impact.pdf

- Eikenberry, A.M. and J.D. Kluver. The Marketization of the Nonprofit Sector: civil society at risk? Public Administration Review, vol. 64 (2): 132-140.

- Elliott, Donald S., Glen E. Holt, Sterling W. Hayden, Leslie Edmonds Holt. 2007. Measuring Your Library’s Value: How to Do a Cost-Benefit Analysis for Your Public Library. ALA Editions (978-0-8389-0923-2)

- Hendriks, Boyd and Ian Wooler, 2006. Establishing the return on investment for information and knowledge services: A practical approach to show added value for information and knowledge centres, corporate libraries and documentation centres. Business Information Review, v. 23 (1): 13-25.

- Holt, Glen E., Donald S. Elliott, Leslie E. Holt, Anne Watts. 2001. Public Library Benefits Valuation Study (St. Louis Public Library): http://www.slpl.lib.mo.us/libsrc/valuationc.htm

- Imholz, S. and Arns, J.W. 2007. Worth Their Weight: An Assessment of the Evolving Field of Library Valuation. Americans for Libraries Council: http://www.bibliotheksportal.de/fileadmin/0themen/Management/dokumente/WorthTheirWeight.pdf

- Lance, Keith Curry and Ray Lyons. 2008. The New LJ Index: Why these measures matter. Library Journal, http://www.libraryjournal.com/article/CA6566452.html

- Luther, Judy. 2008. University Investment in the Library: What’s the Return? A Case Study at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: http://libraryconnect.elsevier.com/lcn/0601/lcn060103.html

- O’Hanlon, Nancy. 2007. Information Literacy in the University Curriculum: Challenges for Outcomes Assessment. portal: Libraries and the Academy 7, no. 2: 169-89.

- Pritchard, Sarah M. 1996. Determining Quality in Academic Libraries. Library Trends, vol. 44 (3): 572-594.

- SLA. 2009. Additional Value Resources: http://www.sla.org/content/learn/members/ipvalue/additionalValue.cfm

- Strouse, Roger. 2003. Demonstrating Value and Return on Investment: The Ongoing Imperative. Information Outlook, v. 7 (3): 15-19. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FWE/is_3_7/ai_99011610

- Strouse, Roger. 2007. ROI for libraries remains high: http://www.outsellinc.com/store/insights/3538

- Weiner, Sharon Gray. 2005. Library Quality and Impact: Is there a Relationship between New Measures and Traditional Measures? Journal of Academic Librarianship, 31(5):432-7.

- Weiner, Sharon. 2009. The Contribution of the Library to the Reputation of a University. Journal of Academic Librarianship, vol. 35 (1): 3-13.

- Yackle, Anna. 2007. What is Your Library’s ROI? (NSLS): http://www.nsls.info/articles/detail.aspx?articleID=137

This is a really insightful and timely post, considering the economic climate we find ourselves in. Thank you!

Another opportunity of interest: NISO Forum on Assessment and Performance Measurement, June 1, 2009 in Baltimore, MD (http://www.niso.org/news/events/2009/assess09/)

I think you both did an excellent job of not only explaining ROIs, but also of applying the term and its use to libraries in particular. All of these issues are pertinent to libraries today. This article will open up much needed discussion on these issues. Thank you both! :)

I’m the director of a small public library in New Jersey. I understand that demonstrating value is important, so last week I began interviewing consultants to conduct an ROI study on the library. The first candidate came in and sat down.

“What’s two plus two?” I asked.

The consultant leaned across my desk and whispered conspiratorially, “What do you want it to be?”

Sorry about the old joke. Still… look at the list of references:

1. Every study was conducted by a librarian or library consultant.

2. None of the studies on ROI can be replicated (that is, they’re non-transferable).

3. All of the studies mentioned, especially the new LJ Index (sponsored by Baker & Taylor’s Bibliostat), seem to choose their measures based on how easy they are to compile rather than on whether they’re actually measuring libraries’ worth relative to each other or, more importantly, to other uses for municipal, institutional, or corporate funds.

While I think the ROI results themselves should be taken with a pillar of salt, the article itself is a good introduction to an important metric; librarians need to understand ROI. The current batch of ROI studies provide some creative ways to begin looking at what we do and how well we do it, but they’re best viewed as ideas we can use in formulating real questions and rigorous studies, not as answers that any of us should cite as fact.

CO also did a public library ROI study.

For links to that and other recent ROI studies of public libraries, interactive ROI tools, and other resources needed to do an ROI study on a shoestring budget, visit the Library Research Service (LRS) website: http://www.LRS.org.

Also, FWIW, I did a well-received, multi-stop ‘roadshow’ of workshops on this topic in NE last year.

This is a great article – your treatment of the various kinds of libraries and consideration of ROI and its relevance to libraries is critical but clearly communicated. One aspect that I could add to the discussion is the use of technology in libraries and the ROI related to it. Karen Coyle’s article talks a little bit about this, though I think mostly in relation to public libraries. Not sure if you came across any others in preparing this post?

@ Gerrit and Laura – thanks for your comments! glad to hear that the content is useful and informative for you.

@ Brett – Your comments and concerns are well-taken. The ROI studies we encountered in prepping this article don’t profess to be comparable or transferable from one library to another library. One of the major downfalls of these studies is that they are context-specific, and those seeking to do cross-library comparisons, cannot rely on these kinds of ROI studies to do that. This was part of the rationale for the LJ Index. The folks who designed the LJ Index wanted to get around the problem of not being able to compare peer libraries. But the result is that the LJ Index doesn’t really provide the sense of a return on investment, which is what the ROI studies intend to do. I’d love to hear about libraries or non-profit organizations that have designed rigorous ROI studies. I think the Illinois study that focuses on ROI for grant dollars is a step in that direction. If folks know of others, please post them or email us.

@ Keith – thanks for sharing the LRS.org set of resources and links on ROI. For those interested in following-up with Keith on his “roadshow” of ROI workshops, his website is http://www.keithcurrylance.com/

@ Hyun-Duck – thanks for the link to Karen Coyle’s article on return on investment for new/evolving technology adoption. I don’t think we came across other articles/work in that flavor, but it’s possible that they exist for the IT realm in general. If I find something that clicks, I’ll post it here.

http://www.hcpl.org/library/value.html

This was an extremely interesting contribution in an extremely interesting blog. I am huge fan :) I am actually writing a German/American library blog myself, and condensed plus translated the general outline of your blog entry there, to bring these ideas into the discussion in Germany.

Pingback : Wert von Informationsarbeit: nützlicher Hinweis zur Messung des ROI von Bibliotheken | LIS in Potsdam

As a part-time employee of a smaller library (2 branches), I feel that the ROI of our facilities has improved tremendously in the past year. Economic difficulties, as well as weather-related catastrophies, forced members of the community to turn to their local library for help. The services we provide to each patron enable him/her to communicate with others via the internet, attend classes to improve job search techniques, experience the lastes in “tech trends”, and apply for passports, to name just a few. Many people who visit our library for the first time have one regret–that they didn’t take advantage of all we have to offer sooner. Getting the community involved plays a key roll in a library’s ROI. Our community is very statified with all that they get for their investment.

Pingback : LibraryTrax » ROI – Return on investment for libraries has never been higher